Funnel chest

Pigeon chest

Aplasia or dysplasia

Pectus excavatum

Pectus carinatum

Ectopia cordis

Cleft sternum

Poland’s syndrome

Asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy

Pectus Excavatum

Pectus excavatum is the anterior depression of the costal wall. It is the most common malformation of the chest cavity, with an incidence of 1 in 400 births. It is more common in men than in women, with a ratio of 5:1. It is more common in the white race, and it is more frequently presented from the first year of life, progressing and becoming more noticeable during the puberty growing phase. The mechanism that provokes it is not completely identified. Some histological studies have shown a weakening in the components of the costal cartilages, which would allow for posterior sternal migration. There is no chromosomal defect, but it has been reported in conjunction with Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, syndactyly, and Klippel–Feil syndrome. Also, a genetic predisposition of approximately 40% of the patients has been detected, who report having a family member with medical history of being a carrier of a malformation of the chest wall.

Preoperative Evaluation

The objective of the preoperative evaluation is to define the morphology and seriousness of the deformation of the sternum, and its functional repercussions both in the lungs and the heart. It is also important to demonstrate that the subject is not allergic to the metallic compounds used when repairing the pectus excavatum, which is present in 2% of the cases.

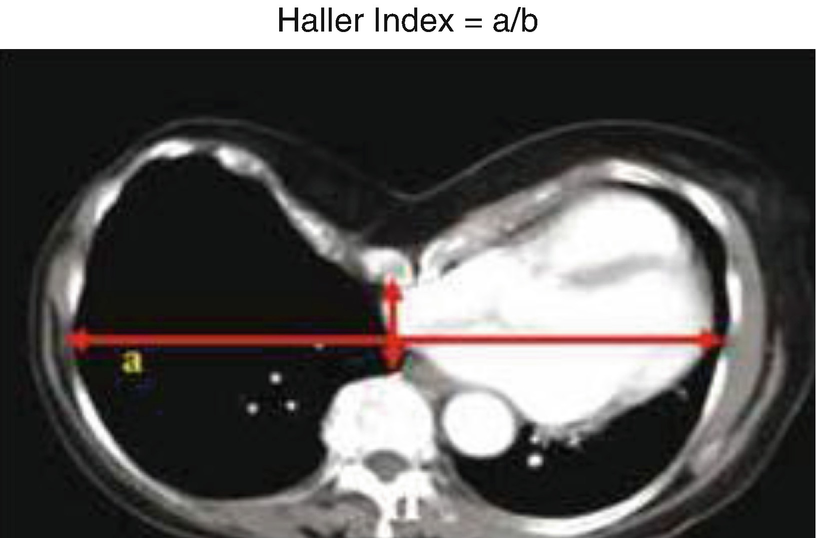

Haller index (TAC)

In the lung evaluation, abnormalities in the lung function can be shown by measuring the forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume in 1 second, and forced expiratory flow of 25–75% of the forced vital capacity.

Regarding the cardiac assessment, the echocardiographic assessment is important, which can show cardiac compression with alterations in the filling and emptying of the right ventricle, while showing deformations of the mitral ring, with prolapse and regurgitation of the mitral valve.

The symptoms produced in the patient are an important part of the preoperative evaluation. Symptoms, such as exercise intolerance, low endurance, and shortness of breath, are reported by the patients with pectus excavatum. Another important aspect is the cosmetic effect that this produces. It limits the normal life of some patients, because they avoid places where the chest deformity will have to be exposed, such as the beach or pools. It has been proven that patients with pectus excavatum have a lower quality of life and that the treatment statistically improves their bodily image.

Treatment

- 1.

Computerized axial tomography or magnetic resonance that shows heart or lung compression with a Haller index of 3.25 or more.

- 2.

Restrictive lung disease proven by a lung function test.

- 3.

Heart compression with abnormalities in the mitral valve, either prolapse or regurgitation.

- 4.

Exercise intolerance, decrease in endurance, and shortness of breath during exercise.

- 5.

Recurrence after an open or minimally invasive surgery.

- 6.

Cosmetic effect produced in patients.

The optimal correction age is between 10 and 14 years of age. In this period the chest cavity is more malleable, which allows for a lower rate of recurrence.

Today, the surgical treatments that are more widely used to correct pectus excavatum are the open technique or Ravitch procedure, and the minimally invasive repair technique or Nuss procedure. The Ravitch technique, described in 1949, consists in an open repair of the defect by a transverse inframammary incision, through which the malformed sternum and the costal cartilages are exposed. Through the anterior approach, costal cartilages are resected, preserving the perichondrium, and anterior sternal osteotomies are performed to correct the sternal depression defect. The wound is closed moving pectoral muscle flaps.

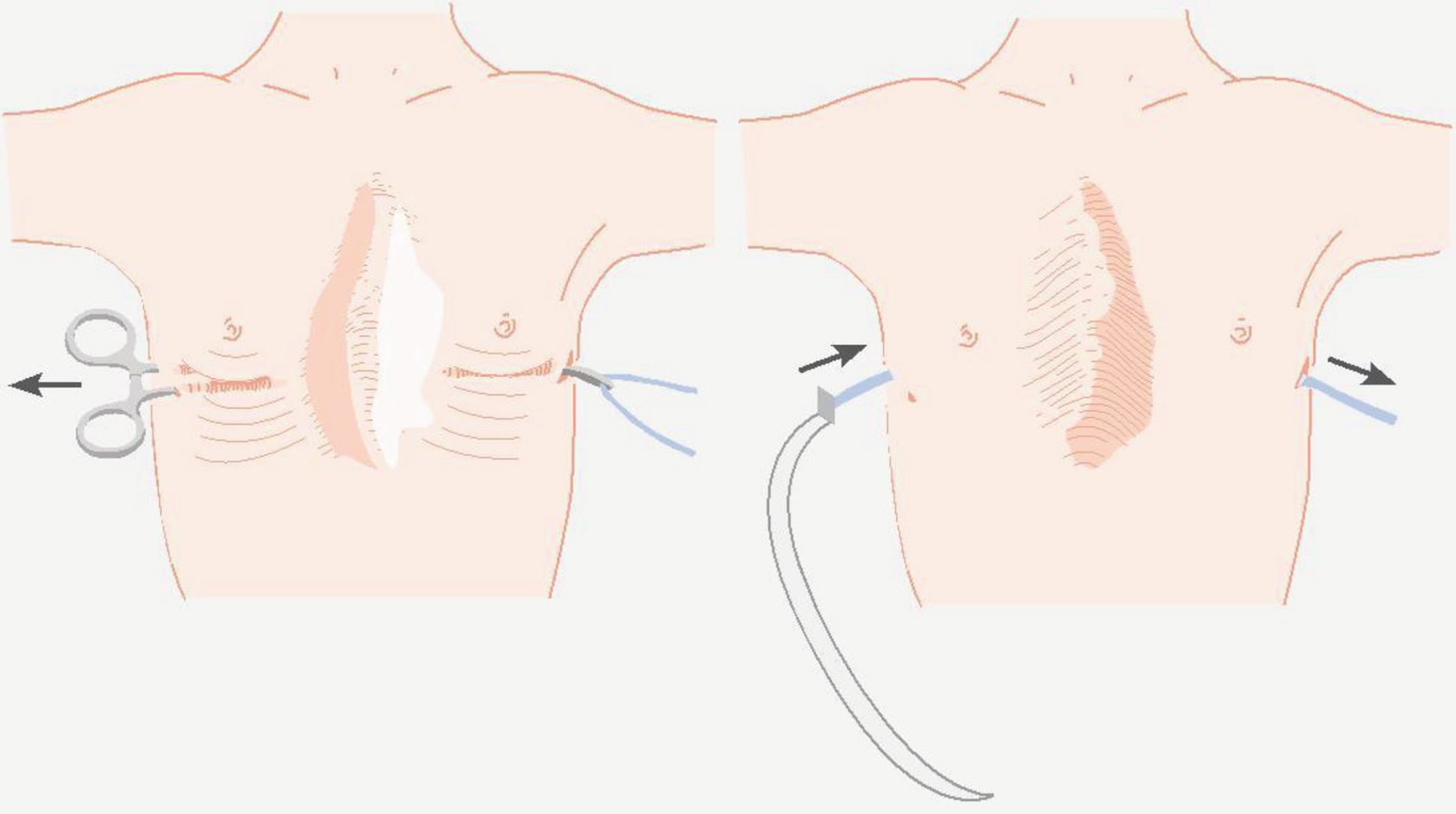

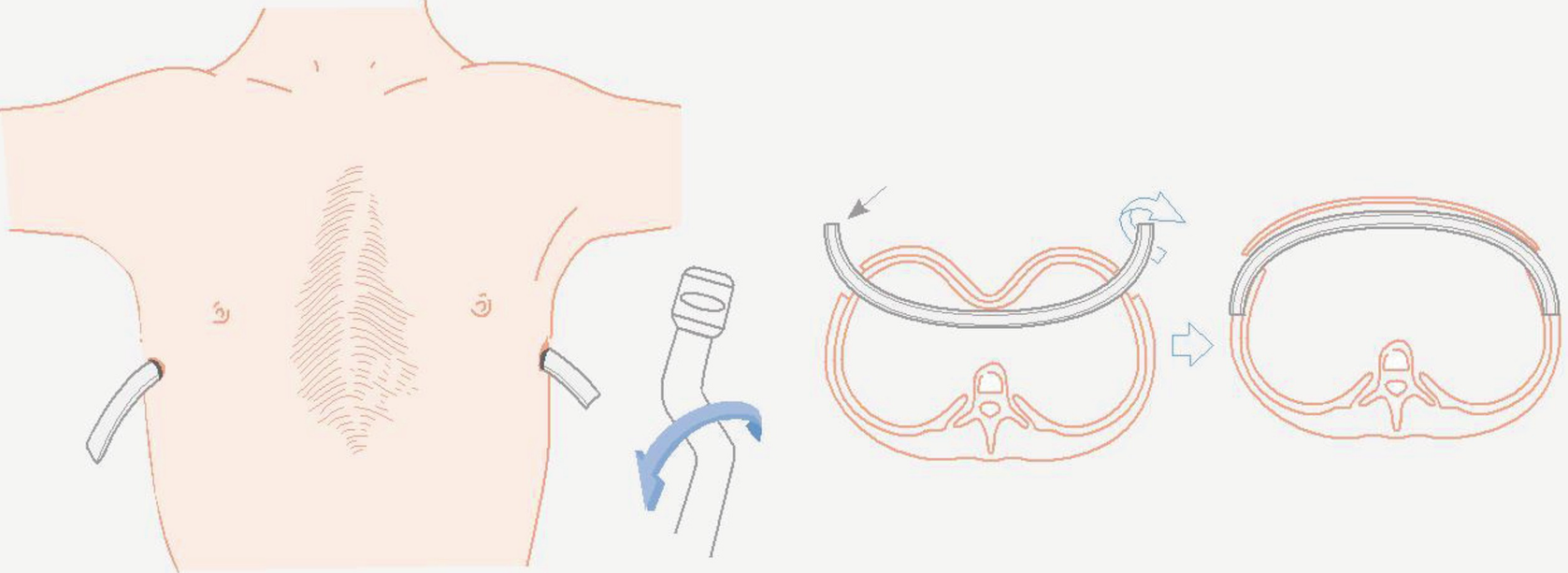

Insertion of the retrosternal bar

Flipping of the retrosternal bar to pop out the sternal defect

Result of the surgical treatment of pectum excavatum

Preoperative (average) | Postoperative (average) | |

|---|---|---|

Haller index | 4.4 | 3.0 |

FVC (predicted %) | 88.0 | 93.0 |

FEV 1 (predicted %) | 87.0 | 90.0 |

TLC (predicted %) | 94.0 | 100.0 |

VO2 during exercise (l/min) | 3.18 | 3.50 |

Pulse oximetry during exercise (VO2/FC) | 13.58 | 16.16 |

The complications of the surgical correction of pectus excavatum are uncommon, the most common being the displacement of the metallic devices, having to reoperate the patient to reposition the bar. Other more infrequent complications are wound infections, retrosternal hematomas, pneumothorax, hemothorax, myocardial lesions, and allergic reactions to metal. These complications tend to be more frequent after the Nuss procedure.

Pectus Carinatum

Pectus carinatum is the second most frequent congenital malformation of the costal wall. Like pectus excavatum, it is more frequent in men than in women, with a ratio of 4:1. It is more frequent to have a late consultation, because it tends to appear after age 11, worsening during puberty.

Preoperative Evaluation

Medical history and complete physical examination are necessary. The protrusion of the sternum with different morphologies will allow the classification of the malformation in its different types. Type 1 or chondrogladiolar is the one that protrudes in the gladiolus or sternal body and lower cartilages. Type 2 or chondromanubrial is less common. Here the manubrium sterni and the higher cartilages protrude. Type 3 or lateral deformities are those in which there is a unilateral protrusion or sternal rotation. There are also mixed forms. Most of the patients will not present symptoms, being mainly a cosmetic problem, which significantly influences the development of a negative body image. Some patients may report musculoskeletal pain in the thorax and epigastrium. The posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray, and in some cases computerized tomography or magnetic resonance can be useful to have a surgical plan. Patients with a Haller index between 1.2 and 2.0 benefit from the correction of the deformity.

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree