EPIDEMIOLOGY AND USUAL CAUSES OF CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE

Stroke is a clinical syndrome characterized by rapidly developing signs or symptoms, or both, of focal neurologic dysfunction with no obvious cause other than vascular origin. Therefore stroke includes both ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebrovascular events.

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is an abrupt, focal loss of neurologic function caused by temporary ischemia, classically defined as lasting less than 24 hours. However, modern imaging techniques have demonstrated that deficits lasting more than a few hours usually result in irreversible cerebral infarction and that most TIAs typically last less than 15 minutes (

1). For the same reason, the term

reversible ischemic neurologic deficit (RIND), referring to symptoms lasting more than 24 hours but less than 7 days, has been abandoned. The colloquial term

cerebrovascular accident (CVA) is also considered outdated, as it implies a fortuitous origin, whereas stroke is usually caused by a well-defined etiopathogenic mechanism.

In 1998, the American Heart Association (AHA) estimated that more than 600,000 strokes and 160,000 deaths of stroke occurred in the United States, which makes stroke the third leading killer of Americans and the leading cause of long-term disability among adults (

2). More recently, a multiracial study performed in the Cincinnati metropolitan area found that more than 730,000 first-ever and recurrent strokes occur each year in this country (

3). Indeed, stroke risk is much greater in African Americans (

4) and Mexican Americans (

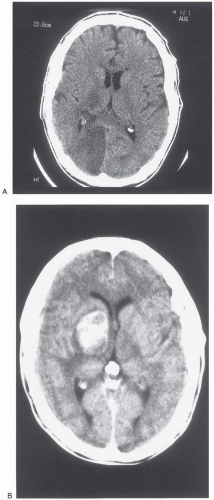

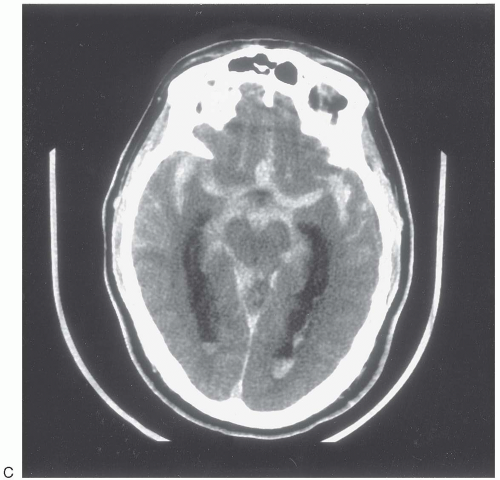

5), suggesting the need for particular prevention efforts in these populations. Approximately 85% of strokes are ischemic, 10% are caused by parenchymal intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), and 5% are secondary to subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

Caring for patients with stroke is an expensive undertaking. Recently, projections for the cost of stroke in the first half of the 21st century exceeded 1.5 trillion dollars (

6). Loss of earnings is the single biggest contributor, but rehabilitation and nursing home costs add considerably to the total. The cost of informal care giving is often underappreciated (

7).

Stroke is not a single disease process but a heterogeneous group of disorders with similar clinical presentation, and thus stroke can have many different underlying causes. The usual causes of ischemic stroke are outlined in

Table 31.1. As with ischemic cardiovascular disease, the most common cause of ischemic cerebrovascular disease is atherosclerosis. Risk factors for ischemic stroke include increasing age, male gender, family history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, cigarette smoking, atrial fibrillation, carotid artery stenosis, and history of stroke, TIA, or myocardial infarction (

8). Other potential risk factors include excessive alcohol intake, sedentary lifestyle, hyperhomocystinemia, hereditary or acquired hypercoagulable states, and obstructive sleep apnea. The usual causes of hemorrhagic stroke (both ICH and SAH) are presented in

Table 31.2.

Of course, the most likely cause of stroke in a given patient depends on the patient’s age, race, ethnicity, and the spectrum of risk factors. In addition, more than one cause of stroke may be present in the same patient.

PRESENTING SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The presenting signs and symptoms of stroke are entirely dependent on the location of brain tissue involved in the vascular process.

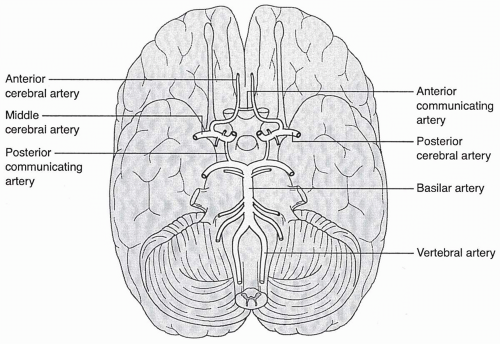

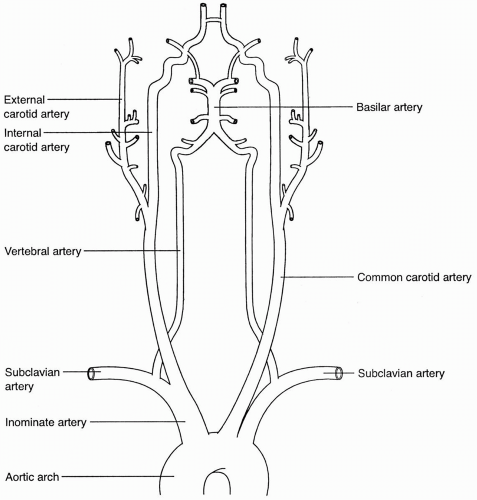

Figures 31.1 and

31.2 provide a review of the extracranial and intracranial vascular anatomy involved in cerebrovascular circulation.

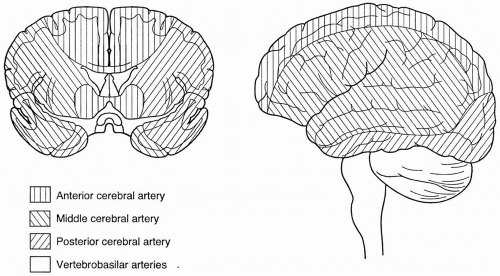

Figure 31.3 outlines the vascular territories of the cerebral circulation. Stroke syndromes have classically been divided into anterior and posterior circulation distributions, on the basis of presenting signs and symptoms, and further subdivided according to the presumed arterial involvement referable to the signs and symptoms. These arterial syndromes and their typical signs and symptoms are outlined in

Table 31.3.

Although stroke signs and symptoms are helpful in localizing the stroke to a specific region of the brain or arterial territory, it is important to remember that the clinical presentation typically does not provide any information about stroke etiology. Headache, vomiting, and decreased level of consciousness are somewhat more common with hemorrhagic stroke, but ischemic stroke can occur with similar symptoms, especially if the vertebrobasilar arterial system is involved or if a hemispheric stroke is large enough to cause mass effect and increased intracranial pressure. Likewise, thrombotic and embolic strokes cannot be distinguished from each other merely on the basis of presenting signs and symptoms.