Central Venous Dilatation and Stenting

Murray L. Shames

Alexis Powell

Introduction

A common complication of hemodialysis access is venous outflow and central vein stenosis. The prevalence of central vein stenosis in the hemodialysis population is reported to be between 15% and 20%. In patients with a history of an indwelling central venous catheter, reported rates can be as high as 40%, while up to 90% of patients with central venous outflow stenosis have had some central venous catheter in the past. Pacemaker and defibrillator wires can also lead to central vein stenosis.

The combination of central venous stenosis and high flow from the dialysis access leads to venous hypertension in the affected arm and potential graft failure. Early symptoms include arm edema and graft pulsatility. Prolonged arm edema can result in chronic venous stasis changes to the arm and even venous ulceration in rare cases.

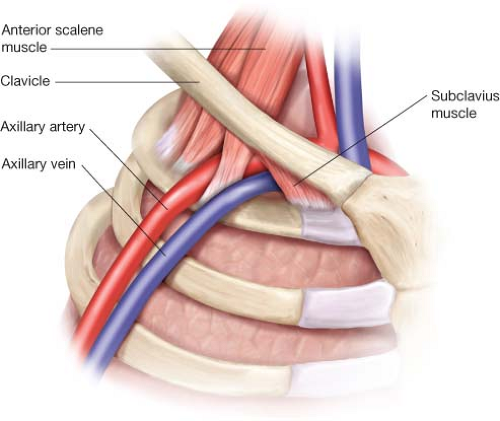

Venous hypertension may cause dialysis recirculation, prolonged bleeding, and ultimately graft failure. A number of factors influence the development of central vein stenosis; high venous flow rates and central venous catheters are the most likely etiologies. A number of authors have also proposed costoclavicular junction stenosis, similar to venous thoracic outlet syndrome as a potential etiology. Bilateral brachiocephalic or superior vena cava occlusion (SVC syndrome) is a complication of prolonged indwelling catheter use and is associated with significant morbidity. This syndrome manifests as bilateral upper extremity edema, edema of the face and neck with multiple dilated venous collaterals over the chest and neck. In many cases there is significant respiratory compromise, often with the inability to lay flat. Urgent intervention is required to prevent relieve symptoms. Treatment of all these lesions with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty has been demonstrated to prolong the useable lifespan of the access site.

Asymptomatic stenosis (treatment can accelerate progression of disease)

Other access complications requiring graft ligation or removal

A number of diagnostic tools are available to assess arteriovenous (AV) access malfunction due to central venous stenosis. Duplex ultrasonography can demonstrate abnormal obstructive waveforms in the fistula/graft as well as demonstrate elevated velocities in the subclavian vein. MR or CT venography is useful to demonstrate central venous anatomy, identifies venous collaterals, and defines the bony anatomy.

Digital subtraction contrast venography is considered the gold-standard for assessment of central venous disease. If necessary, venous lysis or percutaneous thrombectomy can be performed at the time of initial venography. Typically treatment of the central venous stenosis is performed at the time of initial venography.

The patient should be medically stable for an interventional procedure; patient should not be treated with a significantly elevated potassium or if in congestive heart failure from volume overload. Respiratory failure or cardiac dysrhythmia can be fatal in this patient population.

If acute hemodialysis is required, placement of a temporary catheter can be performed. In most cases, hemodialysis can resume immediately after central vein intervention.

Positioning

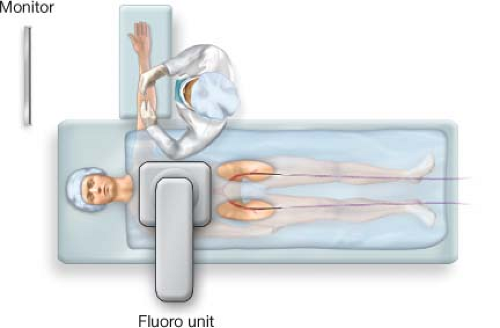

The intervention should ideally be performed in an endovascular suite with fixed imaging systems, although portable imaging systems and fluorocompatible tables in an operating room or outpatient suite are adequate. Conscious sedation and local anesthesia are recommended; in some cases general anesthesia may be required if the patient is unable to lay still. The patient should be positioned supine on a fluorocompatible table with the ipsilateral arm extended.

In some cases femoral access may be required to successfully recanalize occluded central veins, so femoral exposure should also be performed in cases of complete chronic occlusion.

The fluoroscopy equipment should be positioned opposite the operator allowing easy access to the arm and full visualization of the monitors (Fig. 7.1.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree