Case-Based Self-Assessment Questions

Clinical Scenario

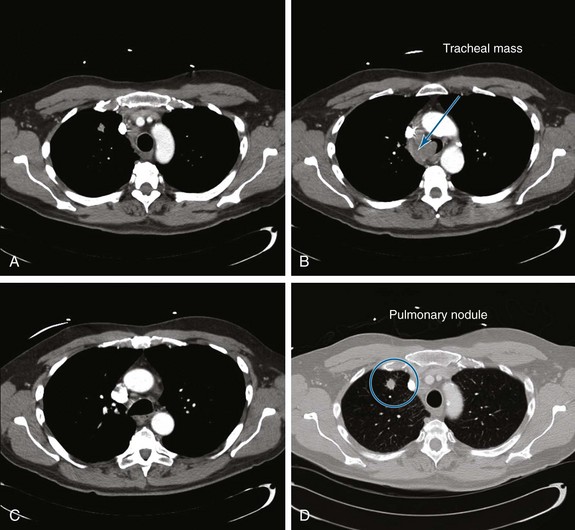

A 55-year-old white male with a 20–pack-year history of smoking presented with syncope, a 2 month history of increasing exertional dyspnea, and a cough that had been refractory to bronchodilators and antibiotics. He was married and lived with his wife. The patient’s father and one brother had died of lung cancer. The emergency department physician believed that the patient was disabled, required special care and assistance, and warranted immediate hospitalization. The physical examination, however, was normal except for stridor heard over the trachea during forced expiration. The workup for syncope included an electrocardiogram, two-dimensional echocardiogram, bilateral carotid duplex ultrasonography, and computed tomography (CT) of the head, all of which were normal. A pulmonary consultant ordered a CT scan of the chest, which revealed a 1.5 cm right upper lung (RUL) nodule and a 4 cm right paratracheal mass invading the trachea (Figure 1).

Estimated survival is an important factor for decision making in all disease processes. If this patient has primary lung cancer, he would be clinically staged IIIB because of tracheal involvement (T4 tumor). In such cases of advanced cancer, prognostic considerations are especially important because treatment goals nearing the end of life may change from efforts to prolong life at all costs, to those of palliating symptoms, preserving quality of life, and maintaining dignity. Estimating survival based on objective data is warranted because physicians’ subjective assessments of predicted survival are often incorrect, with the direction of error being usually optimistic.*1 Patients, in most circumstances, want their doctors to be realistic when it comes to prognosis. Although exact numbers may not be requested by patients or their families, having knowledge of relatively accurate prognostic indicators helps physicians conduct meaningful and honest discussions.

A clinical symptom such as stridor, although a sign of severe laryngeal or tracheal obstruction,2 does not delineate a benign or malignant disease process. In general, stridor and other symptoms of upper or central airway obstruction (CAO), including exertional dyspnea, wheezing, or even syncope, are nonspecific.3 In fact, results from analysis of 100 variables from several studies showed that only dyspnea, dysphagia, weight loss, xerostomia, anorexia, and cognitive impairment were strongly and independently associated with cancer patient survival. These signs and symptoms were outranked, however, by assessment of performance status,1 which deservedly has become a “sixth vital sign” in clinical oncology.† Because performance status is the strongest prognostic indicator of survival in patients with cancer, it is frequently used as an entry criterion and adjustment factor in clinical trials of anticancer treatment.1 One commonly used measure of performance is the Karnofsky Performance Status score (range, 0 to 100 in 10 point increments, where 0 is death and 100 is perfect health), a general measure of functional impairment in which the lower the score, the worse is survival for most serious illnesses.1

This patient was assigned a Karnofsky score of only 40. In the setting of lung cancer, known central airway obstruction, and Karnofsky scores below 50, a combination of interventional bronchoscopy and external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) to relieve the airway obstruction has been shown to be the therapeutic option of choice, often resulting in rapid restoration of airway patency, improved symptoms, improved performance status, and increased survival.4

Question 2: The next appropriate step is to:

A Postpone the procedure until bronchodilator treatments result in decreased peak airway pressure

B Change the endotracheal tube to a larger diameter (e.g., 8 or 8.5 mm), which will accommodate the 6 mm outer diameter flexible bronchoscope

C Cancel the procedure because peak airway pressures are too high

Ideally, a No. 8 or larger ETT is preferred for bronchoscopy because it allows proper ventilation during the procedure and potentially prevents a further increase in peak airway pressure or development of auto-PEEP. These tubes provide at least a 2 mm difference between the scope and the ETT diameter, preventing critical alterations in ventilatory parameters.5 Changing the ETT, however, by extubation and repeat laryngoscopy or by use of a tube exchanger is hazardous in a patient with critical tracheal obstruction. Reintubation may be difficult, and should the airway be lost, ventilation cannot be ensured. A safer approach may be to perform inspection flexible bronchoscopy through the existing ETT while monitoring peak airway pressures, tidal volumes, heart rate, and oxygenation. In case of tachycardia, a rise in blood pressure, or oxygen desaturation during the procedure, the bronchoscope can be immediately withdrawn until stable vital signs return.

Flexible bronchoscopy was performed after a bite block was inserted into the mouth and was secured around the existing ETT. A swivel adapter with a fitted rubber cap was attached, allowing bronchoscopy with minimal loss of tidal volume. The FiO2 was increased to 1.0, starting 5 minutes before the procedure, and continued until after the procedure, then was titrated down to prebronchoscopy levels. PEEP was removed during bronchoscopy to avoid raising peak airway pressures by as much as 25 mm Hg.6 If discontinuation of PEEP had not been feasible, it would have been reduced by 50%. Volume control ventilatory mode was preferred so that the increasing airway resistance secondary to the bronchoscopy would not result in reduced tidal volume. If pressure-controlled ventilation had been used, the peak pressure setting would have been increased to compensate for the loss of tidal volume consequent to the increased resistance. Moderate sedation was achieved with 2 mg intravenous midazolam. Had the patient been unable to cooperate or otherwise tolerate the procedure comfortably, supplemental doses may have been needed in 1- to 2-minute increments and according to moderate sedation guidelines used in our institution. To remove airway secretions, bronchoscopic suction was applied using short, 3 second or less bursts, because as much as 200 to 300 cm3 of the patient’s tidal volume can be removed during each suction period.6

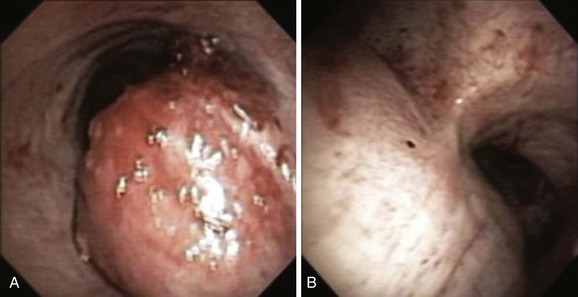

A mass was seen protruding from the right lateral and posterior walls of the lower trachea. The tracheal lumen was narrowed by more than 70%. A severe mixed extrinsic compression and endoluminal obstruction pattern was noted. The remaining airways were normal except for an enlarged carina (Figure 2). The procedure lasted only 1 minute, during which the peak airway pressure increased to 80 cm H2O but without hypoxemia or hemodynamic instability.

A Flattening of the inspiratory curve

B Flattening of the expiratory curve

C Flattening of the inspiratory and expiratory curves

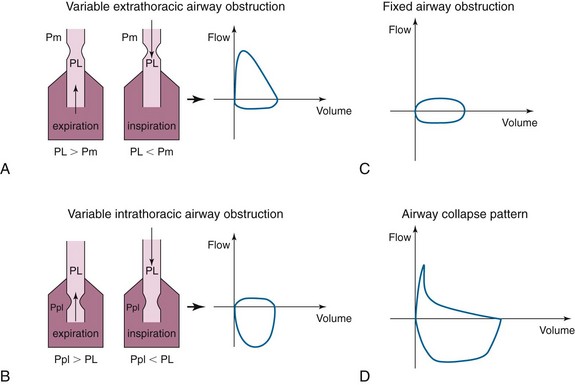

In cases of extrathoracic tracheomalacia, laryngomalacia, or vocal cord processes, the flow-volume loop pattern may be that of flattening of the inspiratory curve (Figure 3, A). This is due to the fact that intraluminal pressure during inspiration (PL) is lower than extraluminal pressure (Pm = atmospheric pressure) for the extrathoracic airway. Therefore, any obstruction in this airway segment will be made worse during inspiration and will cause limitation of the inspiratory flow. During expiration, however, to have an expiratory flow, the intraluminal pressure (PL) is higher than the atmospheric pressure (Pm), the extrathoracic airway will dilate, and the flow will be normal.

The opposite is true in cases of variable intrathoracic obstruction such as intrathoracic tracheomalacia. In this case, the obstruction is worsened during expiration when the pleural pressures (Ppl) exceed the intraluminal pressure (PL) (Figure 3, B), and there will be flattening of the expiratory curve of the flow-volume loop.

Our patient had a tracheal mass limiting airflow both during inspiration and during exhalation. The pattern on the flow-volume loop would likely have been that of blunting of both inspiratory and expiratory curves (Figure 3, C), the so-called square pattern. This pattern may be seen before spirometry yields abnormal results but may not be appreciated until the airway diameter is already narrowed to about 8 to 10 mm and is often masked in severe COPD.

The airway collapse pattern (Figure 3, D) is usually seen in severe COPD and may suggest excessive dynamic airway collapse. This flow-volume loop pattern suggests compression of the mainstem bronchi and trachea. The sudden drop in flow velocity occurs early during expiration when intrathoracic pressure is still increasing, as documented by esophageal pressure measurements. Because there is no reduction of force expelling air from the lungs, the sudden fall in velocity can be explained only by a sudden increase in resistance to airflow, which occurs because of collapse of the central airways. The small, relatively constant flow (i.e., plateau) that occurs after the sudden drop in velocity is consistent with air being forced through a narrow airway.

A Rigid bronchoscopy and restoration of airway patency might allow subsequent systemic therapy in a more stable and spontaneously breathing patient.

B Rigid bronchoscopy and restoration of airway patency will improve exercise capacity and dyspnea.

C Rigid bronchoscopy and restoration of airway patency might allow removal from mechanical ventilatory support and discharge from the intensive care unit.

Patients with respiratory failure and malignant CAO treated by bronchoscopic intervention, who subsequently underwent definitive systemic therapy, were shown to have improved dyspnea and longer survival (median, 38.2 months; range, 1.7 to 57.0 months) compared with those who did not undergo bronchoscopic intervention (median, 6.2 months; range, 0.1 to 33.7 months; P < .001).7 Restoring airway patency also improves exercise capacity and dyspnea.7 In this study, a significant improvement in symptoms was noted in 94% of patients undergoing airway stent insertion, although ultimately 40% of patients required multiple bronchoscopic procedures. This raises concerns about the cost per quality of life-years gained in patients with advanced disease.8 The expense of palliative interventional procedures such as bronchoscopic laser resection and stent insertion, however, is probably small compared with the costs of repeated external beam radiation therapy or prolonged hospitalization in the intensive care unit. Rapid tissue diagnosis, restoration of airway patency, subsequent extubation and removal from mechanical ventilation, and discharge from the intensive care unit to a ward or even outpatient setting because of this single procedure likely result in considerable savings that positively impact health care costs and resource utilization.

Evidence that removal from mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients with airway obstruction and respiratory failure is possible because of interventional bronchoscopic procedures is limited but reproducible. Lo et al. successfully extubated 7 of 7 patients who were on mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure from malignant obstruction.9 Colt and Harrell successfully removed ventilatory support in 10 of 19 patients (52.6%) with malignant and benign obstruction,10 suggesting that when procedures were unsuccessful, immediate referral to hospice and comfort care was justified. Schaffer and Allen inserted metal stents in 6 patients with malignant CAO and in 2 with benign CAO, successfully extubating 6 of them 2 to 11 days later.11 Furthermore, successful removal from mechanical ventilation has been associated with prolonged survival when systemic treatment is also administered (98 vs. 8.5 days).12

During our dialogue with the patient’s wife, it was believed that the risks of further airway compromise and clinical deterioration were outweighed by the benefit of restoring airway patency with an ability to immediately diagnose the abnormality, wean the patient from mechanical ventilation, and offer systemic therapy. Although we planned to make the diagnosis on frozen section of the tumor removed from the airway, we could have also chosen to perform endobronchial needle aspiration (EBNA), brushing, or endobronchial forceps biopsy. In our experience, EBNA has a lower risk of bleeding than brushing or biopsy, and it provides immediate diagnosis when on-site cytologic examination is available. On-site cytology is not yet the standard of practice in many institutions; however, it may increase procedure-related costs, and, contrary to endobronchial biopsy, tissue architecture is not seen.13

A CT-guided percutaneous needle aspiration of the right upper lobe nodule

B Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) radial probe-guided transbronchial biopsy of the nodule

C Electromagnetic navigation (EMN) for guiding transbronchial biopsy of the nodule

D Surgical consultation for video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) or thoracotomy

E Flexible bronchoscopy with EBNA at the bedside in the intensive care unit (ICU)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree