Cardiovascular Complications

CARDIAC TAMPONADE

Cardiac tamponade involves a rapid increase in intrapericardial pressure, which impairs diastolic filling of the heart and reduces cardiac output. The increase in pressure usually results from blood or fluid accumulation in the pericardial sac. If fluid accumulates rapidly, as little as 250 ml can create an emergency situation.

Prognosis depends on the rate of fluid accumulation. If it accumulates rapidly, cardiac tamponade requires emergency life-saving measures to prevent death. Slow accumulation and an increase in pressure, as in pericardial effusion associated with cancer, may not produce immediate signs and symptoms because the fibrous wall of the pericardial sac can gradually stretch to accommodate as much as 1 to 2 L of fluid.

Pathophysiology

In cardiac tamponade, the progressive accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac causes compression of the heart chambers. This compression obstructs blood flow into the ventricles and reduces the amount of blood that can be pumped out of the heart with each contraction. (See Understanding cardiac tamponade, page 476.)

Each time the ventricles contract, more fluid accumulates in the pericardial sac. This further limits the amount of blood that can fill the ventricular chambers—especially the left ventricle—during the next cardiac cycle.

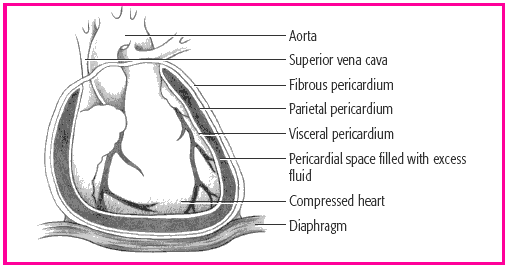

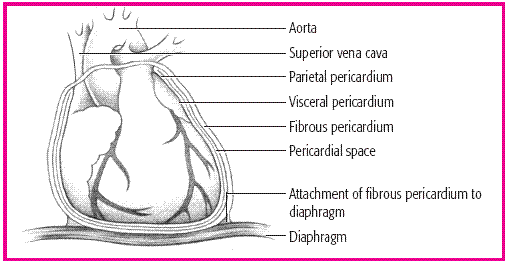

UP CLOSE

The pericardial sac, which surrounds and protects the heart, is composed of several layers. The fibrous pericardium is the tough outermost membrane; the inner membrane, called the serous membrane, consists of the visceral and parietal layers. The visceral layer clings to the heart and is also known as the epicardial layer of the heart. The parietal layer lies between the visceral layer and the fibrous pericardium. The pericardial space—between the visceral and parietal layers-contains 10 to 30 ml of pericardial fluid. This fluid lubricates the layers and minimizes friction when the heart contracts.

NORMAL HEART AND PERICARDIUM

|

In cardiac tamponade, blood or fluid fills the pericardial space, compressing the heart chambers, increasing intracardiac pressure, and obstructing venous return. As blood flow into the ventricles falls, so does cardiac output. Without prompt treatment, low cardiac output can be fatal.

The amount of fluid necessary to cause cardiac tamponade varies greatly; it may be as little as 50 ml when the fluid accumulates rapidly or more than 2 L when the fluid accumulates slowly and the pericardium stretches to adapt.

Cardiac tamponade may be idiopathic (Dressler’s syndrome) or may result from:

effusion (in patients with cancer, bacterial infection, tuberculosis or, rarely, acute rheumatic fever)

hemorrhage from trauma (such as a gunshot or stab wound to the chest and perforation by catheter during cardiac or central venous catheterization, or after cardiac surgery)

hemorrhage from nontraumatic causes (such as rupture of the heart or great vessels, or anticoagulant therapy in a patient with pericarditis)

viral, postirradiation, or idiopathic pericarditis

acute myocardial infarction

chronic renal failure during dialysis

pneumothorax causing pressure against the heart

drug reaction (such as with procainamide, hydralazine, minoxidil, isoniazid, penicillin, methysergide, and daunorubicin)

a connective tissue disorder (such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatic fever, vasculitis, or scleroderma).

Complications

Reduced cardiac output (fatal without prompt treatment)

Assessment findings

The patient’s history may show a disorder that can cause cardiac tamponade.

He may report acute pain and dyspnea, sitting upright and leaning forward to facilitate breathing and lessen the pain. He may be orthopneic, diaphoretic, anxious, and restless, and appear pale or cyanotic.

You may note jugular vein distention produced by increased venous pressure, although this may not be present if the patient is hypovolemic.

Palpation of the peripheral pulses may disclose rapid, weak pulses. Palpation of the upper quadrant may reveal hepatomegaly.

Percussion may disclose a widening area of flatness across the anterior chest wall, indicating a large effusion. Hepatomegaly may also be noted.

Auscultation of the blood pressure may demonstrate a decreased arterial blood pressure, paradoxical pulse (an abnormal inspiratory drop in systemic blood pressure greater than 15 mm Hg), and narrow pulse pressure.

Heart sounds may be muffled. A quiet heart with faint sounds usually accompanies only severe tamponade and occurs within minutes of the tamponade, as happens with cardiac rupture or trauma. The lungs are clear.

Diagnostic test results

The following test results are characteristic of cardiac tamponade:

Chest X-rays show slightly widened mediastinum and enlargement of the cardiac silhouette.

Electrocardiography (ECG) is useful to rule out other cardiac disorders. The QRS complex may be reduced, and electrical alternans of the P wave, QRS complex, and T wave may be present. Generalized ST-segment elevation is noted in all leads.

Pulmonary artery pressure monitoring detects increased right atrial pressure, right ventricular diastolic pressure, and central venous pressure (CVP).

Echocardiography records pericardial effusion with signs of right ventricular and atrial compression.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to relieve intrapericardial pressure and cardiac compression by removing accumulated blood or fluid. Pericardiocentesis (needle aspiration of the pericardial cavity) or surgical creation of an opening dramatically improves systemic arterial pressure and cardiac output with aspiration of as little as 25 ml of fluid. A drain may be inserted into the pericardial sac to drain the effusion. (See Aspirating pericardial fluid.) This may be left in until the effusion process stops or the corrective action (pericardial window) is performed.

If tamponade or effusions or adhesions from chronic pericarditis recur, a portion or all of the pericardium may need to be removed to allow adequate ventricular filling and contraction. A pericardial window may be performed, which involves removing a portion of the pericardium to permit excess pericardial fluid to drain into the pleural space. In more severe cases, removal of the toughened encasing pericardium (pericardectomy) may be necessary.

In the hypotensive patient, trial volume loading with I.V. normal saline solution with albumin and, perhaps, an inotropic drug such as dopamine is necessary to maintain cardiac output.

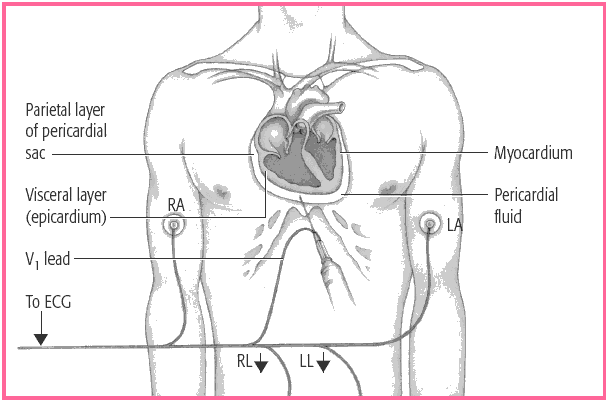

ASPIRATING PERICARDIAL FLUID

In pericardiocentesis, a needle and syringe assembly is inserted through the chest wall into the pericardial sac, as illustrated here. Electrocardiographic monitoring with a leadwire attached to the needle and electrodes placed on the limbs (right arm [RA], right leg [RL], left arm [LA], and left leg [LL]) helps to ensure proper needle placement and to avoid damage to the heart.

|

Depending on the cause of tamponade, additional treatment may include:

for traumatic injury, blood transfusion or a thoracotomy to drain reaccumulating fluid or to repair bleeding sites

for heparin-induced tamponade, the heparin antagonist protamine

for warfarin-induced tamponade, vitamin K.

Nursing interventions

Monitor the patient with cardiac tamponade in the intensive care unit. Check for signs of increasing tamponade, increasing dyspnea, and arrhythmias.

FOR A PATIENT WHO HAS UNDERGONE PERICARDIOCENTESIS

Reassure the patient to reduce his anxiety.

Gather a pericardiocentesis tray, an ECG machine, and an emergency cart with a defibrillator at the bedside. Make sure the equipment is turned on and ready to be used. Position the patient at a

45- to 60-degree angle. Connect the precordial ECG lead to the hub of the aspiration needle with an alligator clamp and connecting wire, and assist with fluid aspiration. When the needle touches the myocardium, you see ST-segment elevation or premature ventricular contractions.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH CARDIAC TAMPONADE

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH CARDIAC TAMPONADE

Teach the patient signs and symptoms of recurrent effusion, infection, and cardiac arrhythmias to report to the practitioner.

Review medications and adverse effects.

Review incisional care if appropriate.

Monitor blood pressure and CVP during and after pericardiocentesis. Infuse I.V. solutions, as ordered, to maintain blood pressure. Watch for a decrease in CVP and a concomitant increase in blood pressure, which indicate relief of cardiac compression.

Administer oxygen therapy as needed.

RED FLAG

RED FLAGWatch for complications of pericardiocentesis, such as ventricular fibrillation, vasovagal arrest, and coronary artery or cardiac chamber puncture. Closely monitor cardiac rhythm strip changes, blood pressure, pulse rate, level of consciousness, and urine output.

FOR A PATIENT WHO HAS UNDERGONE THORACOTOMY

Give an antibiotic, protamine, or vitamin K.

Postoperatively monitor critical parameters, such as vital signs and arterial blood gas levels, and assess heart and breath sounds. Give an analgesic as ordered. Maintain the chest drainage system, and be alert for complications, such as hemorrhage and arrhythmias. (See Teaching the patient with cardiac tamponade.)

CARDIOGENIC SHOCK

Cardiogenic shock is a condition of diminished cardiac output that severely impairs tissue perfusion. It’s sometimes called pump failure. Cardiogenic shock can occur as a serious complication in nearly 15% of all patients who are hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (MI). It typically affects patients whose area of infarction involves 40%

or more of left ventricular muscle mass; in such patients, mortality may exceed 85%.

or more of left ventricular muscle mass; in such patients, mortality may exceed 85%.

Pathophysiology

In cardiogenic shock, the left ventricle can’t maintain adequate cardiac output. Compensatory mechanisms increase heart rate, strengthen myocardial contractions, promote sodium and water retention, and cause selective vasoconstriction. However, these mechanisms increase myocardial workload and oxygen consumption, which reduces the heart’s ability to pump blood, especially if the patient has myocardial ischemia. Consequently, blood backs up, resulting in pulmonary edema. Eventually, cardiac output falls and multisystem organ failure develops as the compensatory mechanisms fail to maintain perfusion.

Cardiogenic shock can result from any condition that causes significant left ventricular dysfunction with reduced cardiac output, such as an MI (most common), myocardial ischemia, papillary muscle dysfunction, and end-stage cardiomyopathy.

Other causes include myocarditis and depression of myocardial contractility after cardiac arrest and prolonged cardiac surgery. Mechanical abnormalities of the ventricle, such as acute mitral or aortic insufficiency or an acutely acquired ventricular septal defect or ventricular aneurysm, may also result in cardiogenic shock.

Complications

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Acute tubular necrosis

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Cerebral hypoxia

Death

Assessment findings

Typically, the patient’s history includes a disorder that severely decreases left ventricular function, such as an MI or cardiomyopathy.

Patients with underlying cardiac disease may complain of angina because of decreased myocardial perfusion and oxygenation.

Urine output is usually less than 20 ml/hour.

Inspection usually reveals pale skin, decreased sensorium, and rapid, shallow respirations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

RED FLAG

RED FLAG