Racquet sports may evoke excessive aerobic and/or cardiac demands for many coronary patients with impaired cardiorespiratory fitness. We evaluated the cardiorespiratory and hemodynamic responses to table tennis in clinically stable patients with coronary disease. Low-risk cardiac men (n = 10, mean ± SD, age = 67.6 ± 8.8 years) satisfying inclusion criteria (functional capacity ≤8 metabolic equivalents [METs] without evidence of impaired left ventricular function, significant dysrhythmias, signs and/or symptoms of myocardial ischemia, or orthopedic limitations), completed the study. Patients were monitored for heart rate (HR), blood pressure, rating of perceived exertion (6 to 20 scale), and electrocardiographic responses during a 10-minute bout of recreational table tennis. Metabolic data were directly obtained using breath-by-breath measurements of oxygen consumption. Treadmill testing in our subjects revealed an average estimated exercise capacity of 6.8 ± 1.4 METs. Aerobic requirements of table tennis averaged 3.2 ± 0.5 METs; however, there was considerable variation in the oxygen consumption response to play (2.0 to 5.0 METs). Peak HR and systolic blood pressure responses during table tennis were 98.0 ± 8.5 beats/min and 140.4 ± 16.2 mm Hg, respectively. The average HR during table tennis represented 83% of the highest HR attained during treadmill testing. Rating of perceived exertion during table tennis averaged 10.6 ± 1.7, signifying “fairly light” exertion. In conclusion, table tennis represents a relatively safe and potentially beneficial leisure-time activity for cardiac patients with impaired levels of cardiorespiratory fitness. The average aerobic requirement of table tennis approximated prescribed exercise training workloads for most of our patients.

In patients with known or occult coronary artery disease (CAD), strenuous physical activity, especially when sudden, unaccustomed, or involving high levels of anaerobic metabolism, may increase the risk for acute myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. For example, vigorous competitive racquet sports, including singles tennis and squash, are associated with a greater incidence of acute cardiac events than more moderate activities and appear to be contraindicated in many patients with CAD. We hypothesized that table tennis, with its abbreviated court size and limited somatic movement, may be associated with reduced physiological demands, making it more appropriate as a leisure-time activity for the cardiac patient. The present study evaluated the electrocardiographic (ECG), cardiorespiratory, hemodynamic, and perceived exertion responses to table tennis in cardiac patients and whether these responses approximated their prescribed aerobic requirements for exercise training.

Methods

Our study group consisted of 10 men in the Beaumont outpatient (phase 3) cardiac rehabilitation program (range 1 to 7 years) who volunteered to participate in the field testing (i.e., table tennis) and met the following eligibility criteria: low-risk clinical status (no significant left ventricular dysfunction [e.g., ejection fraction <40%], threatening arrhythmias, or exercise-induced signs and/or symptoms of myocardial ischemia) and a peak or symptom-limited functional capacity ≤8 metabolic equivalents (METs), based on graded exercise testing. Patients with recent myocardial infarction (<3 months), bundle branch block, digoxin therapy, left ventricular hypertrophy, pacemaker and/or implantable cardioverter defibrillator, unstable CAD and/or heart failure, severe pulmonary disease, activity-limiting arthritis, or other musculoskeletal problems were excluded. The study included 8 patients who had a previous myocardial infarction, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass grafting, or combinations thereof and 2 with angiographically documented CAD. Using cardiac catheterization, echocardiographic, or myocardial perfusion imaging data, their mean ± SD left ventricular ejection fraction was 63.9 ± 3.9%. Medical records indicated a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and congestive heart failure in 10, 9, 5 and 2 patients, respectively.

The cardiac rehabilitation participant’s (n = 10) mean ± SD age was 67.6 ± 8.8 years; height was 69.6 ± 2.7 inches; weight was 213.3 ± 41.2 pounds; and body mass index, 30.8 ± 4.7 kg/m 2 . Phase 3 exercise intensities (50% to 80% of oxygen consumption [VO 2 ] or heart rate [HR] reserve) were based on the patient’s functional capacity and highest HR attained during peak or symptom-limited exercise testing (Bruce or modified Bruce protocol), using the attained speed, grade, and duration to estimate METs. Prescribed medications in our study subjects included β blockers, statins, aspirin, clopidogrel, antiarrhythmic drugs, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Each patient gave written informed consent before participation in the study protocol, which was approved by the institutional human investigation committee.

Patients were monitored continuously using a portable metabolic measurement system (Cosmed K4b2, Rome, Italy) and ECG telemetry (ScottCare TeleRehab Advantage, Cleveland, Ohio) during a bout of table tennis. The metabolic unit, which was calibrated immediately before individual data collection, includes a computer assembly for online 60-second calculations of VO 2 , expressed as mL O 2 /kg/min or METs. We used the definition of a MET as described by Balke to be 3.5 ml O 2 /kg/min, often characterized as the aerobic or energy cost of resting quietly. Blood pressure was monitored by the standard cuff method, and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) was assessed using the category scale (6 to 20). These measurements were obtained at the end of each 10-minute bout of table tennis. Patients were introduced to the table tennis protocol and had opportunities for “play” before actual data collection. Individualized data collection involved 2 participants who met the inclusion criteria. After a preliminary low-level 10-minute treadmill warm-up, both patients performed ∼20 minutes of total activity, divided into two 10-minute portions, with a 5- to 10-minute rest period between exercise bouts. Minute-by-minute HR responses were determined by ECG telemetry during the last 15 seconds of each minute. To facilitate continued play and evoke “steady-state” responses, ball retrievers were used to minimize break time during play. After activity, both subjects cooled down in a seated rest position, allowing the HR to return to within 10 beats/min of the baseline or resting HR. Subjects then repeated the recreational activity bout (table tennis play) with identical measurements obtained on the second participant.

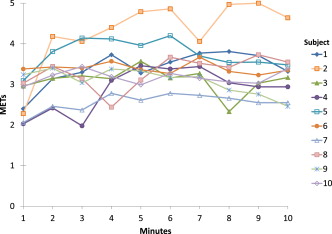

Means and SDs were calculated for selected variables. ECG, hemodynamic, and the mean and highest observed cardiorespiratory responses during table tennis were compared with those obtained from the subject’s peak or symptom-limited exercise test. Paired t tests were used to facilitate these comparisons. Minute-by-minute values for VO 2 during table tennis for all subjects were plotted over time. A value of p ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Each subject completed the field testing protocol (table tennis) without adverse signs or symptoms, ischemic ECG changes, or musculoskeletal complications. Baseline HR and systolic blood pressure before treadmill and field testing protocols were comparable, 75.2 ± 13.2 versus 74.1 ± 7.8 beats/min and 124.2 ± 15.9 versus 119.2 ± 17.1 mm Hg, respectively. Peak VO 2 , estimated from preliminary treadmill testing, was 6.8 ± 1.4 METs, corresponding to a poor-to-very poor level of cardiorespiratory fitness, based on age and gender norms.

To compare absolute and relative cardiorespiratory responses during peak treadmill testing versus recreational table tennis, average values for HR, VO 2 , systolic blood pressure, and RPE are listed in Table 1 . Peak HRs during table tennis, 98 ± 9 beats/min, were significantly lower than those achieved during treadmill testing, 118 ± 17 beats/min (p <0.01). The levels of effort during table tennis also yielded lesser RPEs, 11 ± 2 versus 16 ± 1 (p <0.0001). Aerobic requirements for table tennis averaged 3.2 ± 0.5 METs, corresponding to 47% of their estimated aerobic capacity (moderate intensity activity). Nevertheless, a minute-by-minute plot of VO 2 values for all subjects revealed gradual increases over the first few minutes of play and considerable variation in aerobic requirements (2.0 to 5.0 METs; Figure 1 ). Peak HR during table tennis represented 83% of the highest HR attained during treadmill testing. In contrast, RPE at the completion of the 10-minute table tennis bout corresponded to “fairly light.”

| Variable ∗ /Modality | Treadmill Testing | Table Tennis † | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | 117.6 ± 16.9 | 98.0 ± 8.5 | .0106 |

| VO 2 (METs) | 6.8 ± 1.4 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | .0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 165 ± 21.6 | 140.4 ± 16.2 | .0303 |

| Rating of perceived exertion (6-20 scale) | 15.7 ± 0.9 | 10.6 ± 1.7 | .0001 |

∗ bpm = beats per minute; mm Hg = millimeters of mercury.

† All responses were significantly lower during table tennis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree