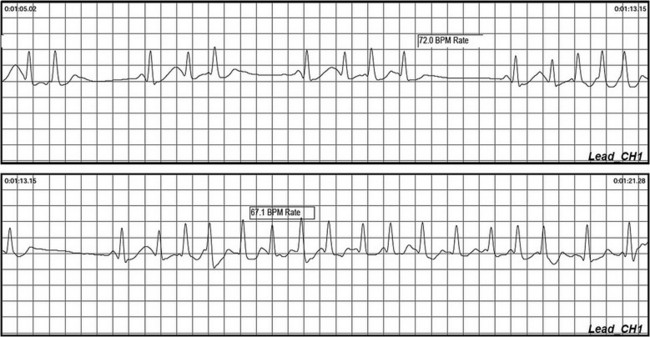

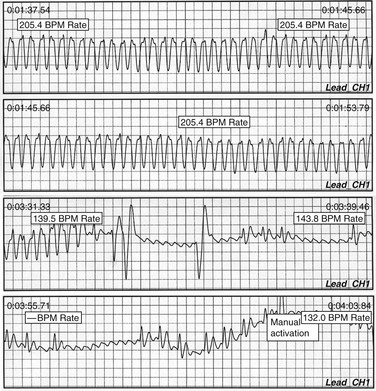

64 Ambulatory cardiac monitoring to detect arrhythmia became practical with the development of Holter monitoring and its subsequent derivatives. The clinician is currently armed with an array of tools to provide progressively longer durations of electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring, to obtain a rhythm profile potentially useful in risk stratification, and to establish a symptom rhythm correlation in patients with infrequent symptoms (Figure 64-1). Figure 64-1 Ambulatory recording during palpitations and presyncope. Note the burst of atrial tachycardia, with associated brief pauses. Holter monitoring has several drawbacks. Patients may not experience symptoms or cardiac arrhythmias during the usual Holter recording periods. In patients with syncope, the likelihood of another syncopal episode occurring during the monitoring period is the major limiting factor. Presyncope is a more common event during ambulatory monitoring but is less likely to be associated with an arrhythmia.1,2 The ubiquity of presyncope as a symptom in the community makes its usefulness as a surrogate for syncope relatively uncertain. The physical size of the device may hinder the ability of patients to sleep comfortably or to engage in activities that precipitate symptoms. Patients are further inconvenienced because the devices have to be removed while showering. Observations on Holter monitoring must be correlated with clinical context in the absence of symptoms. Significant variability is often noted in patient documentation of activated events such that accurate symptom–rhythm correlation is undermined. It is not surprising that Holter monitoring has a low diagnostic yield. In several large series using 12 h or more of ambulatory monitoring for investigation of syncope, only 4% had recurrence of symptoms during monitoring.3,4 The overall diagnostic yield of ambulatory or Holter monitoring was 19%. These studies reported symptoms that were not associated with arrhythmias in 15% of cases. The causal relationship between arrhythmia and syncope was frequently uncertain. Uncommon asymptomatic arrhythmias such as prolonged sinus pauses, atrioventricular block (such as Mobitz type II block), and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia can provide important contributions to the diagnosis, instigating further investigations to rule out structural heart disease and other precipitating factors. Although these observations necessitate prompt attention, it is important to interpret the results in the clinical context of the syncopal presentation and to not unduly exclude common causes of syncope such as neurocardiogenic syncope. It is also important to understand that a normal Holter monitor does not exclude an arrhythmic cause for syncope. In fact, an arrhythmic cause is typically the case. If the pretest probability is high for an arrhythmic cause, further investigations such as more prolonged monitoring or cardiac electrophysiological studies are required. In a study that evaluated extension of ambulatory Holter monitoring duration to 72 h,5 an increased number of asymptomatic arrhythmias were detected, but the overall diagnostic yield was not increased. Transtelephonic monitors are a form of noncontinuous ambulatory recording that is convenient for patient use. During symptomatic episodes, the patient activates the device, which then records electrocardiographic signals. The recorded event must be directly transmitted by an analog telephone line to a receiving center (Figures 64-2 and 64-3). The received signal is then converted to an analog recording that is displayed or printed as a single lead rhythm strip. The device has solid-state memory capacity, allowing recording and storage of electrocardiographic signals during symptoms. Electrocardiographic signals are collected prospectively for 1 to 2 minutes upon patient activation. The major disadvantages of such devices include the need for patient activation; missing asymptomatic arrhythmias, which requiring that the symptoms persist long enough for the device to record the event; and the inability to record events that surround the onset of symptoms. Figure 64-3 External loop recorder download from a patient with near syncope with palpitations. Wide QRS complex tachycardia is noted at 206 bpm, which subsequently demonstrates underlying atrial flutter with much slower conduction, and subsequent patient activation to capture the event. No recognized intervention led to an abrupt reduction in conduction rate. Emerging technologies such as the iRhythm device promise minimally invasive intermediate-term monitoring without classic electrodes and battery systems, enabling a patch-based “all in one” system to facilitate 7 to 14 d of monitoring (Figure 64-4). These technologies are currently being evaluated with promising early results, but larger-scale or comparative studies have not been performed. Two prospective comparative trials are under way (Holter vs. patch), as is a third trial, which was undertaken to validate detection of asymptomatic atrial fibrillation. Publications are anticipated by the time of the release of this chapter. Wrist and mobile phone-based recording devices show promise as minimally invasive recording devices, with rapidly evolving technology. A recent preliminary report indicated the potential pulse detection capability of a wrist recording device termed the wriskwatch,6 which brought attention to alternate means of recording multiple physiological parameters. Continuous ambulatory monitoring with data transmission to a central monitoring station staffed by Health Professionals (Cardionet, San Diego California) has emerged in the United States as a useful resource to extend traditional Holter monitoring beyond 48 h. This technique is typically used for 7 to 14 d, and has shown incremental benefit over a standard external loop recorder in diagnosing or excluding arrhythmia.7 This approach also provides the added layer of monitoring center involvement, which enhances responsiveness to changes seen during monitoring. Unfortunately, this substantially increases cost. An external loop recorder continuously records and stores a single external modified limb lead electrogram with a 4- to 18-min memory buffer (see Figure 64-2). After the onset of spontaneous symptoms, the patient activates the device storing the previous 3 to 14 min and the following 1 to 4 min of recorded information. The captured rhythm strip subsequently can be uploaded and analyzed, often providing critical information regarding onset and termination of the arrhythmia (see Figure 64-2

Cardiac Monitoring

Short- and Long-Term Recording

Short-Term Recording

Holter Monitoring

Nonelectrode Event Recorders

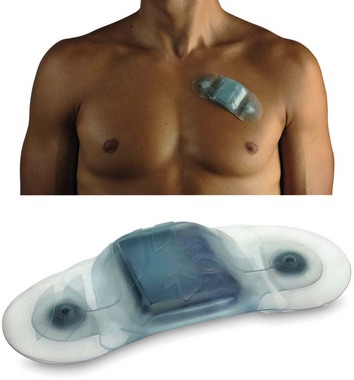

New Technology

Patch

Wrist Recorders

Intermediate-Duration Monitoring

Extended Holter

External Loop Recorders

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Cardiac Monitoring: Short- and Long-Term Recording