Chapter 3 Cardiac Malpositions

Dextrocardia in situs inversus was known to the anatomist-surgeon Marco Aurelio Severino in 1643 and was one of the first recognized congenital malformations of the heart.1 Nearly a century and a half elapsed before Matthew Baillie’s2 account of “complete transposition in the human subject, of the thoracic and abdominal viscera, to the opposite side from what is natural.”

Cardiac malpositions, which have a prevalence rate of 0.10 per 1000 live births,3 refer to hearts that are located abnormally within the thoracic cavity or that are located outside the thoracic cavity—ectopia cordis.4 In 1901, Paltauf5 published remarkable illustrations that distinguished the various types of dextrocardia; and in 1928, the first useful classification of cardiac malpositions was proposed.6 Subsequent observations by Lichtman7 and by de la Cruz8 shed light on the embryologic bases of the malpositions; the landmark observations of van Praagh9 confirmed the validity of those assumptions. Campbell’s10–12 diagrams in the 1950s and 1960s, and Elliott’s13 radiologic classification in 1966, set the stage for the clinical recognition of cardiac malpositions.

The genetics of cardiac midline and lateral defects occur along three geometric axes: anteroposterior, dorsal-ventral, and left-right.14 Genes expressed in dorsal midline cells coordinate the development of the three embryonic axes, driving the cardiac tube to loop in the appropriate direction relative to body axes. The left-right axis is established at approximately the 18th day after fertilization.14 Both bilateral left-sidedness and bilateral right-sidedness have been reported in members of the same family, which implies that the two conditions are different manifestations of a primary defect in lateralization.15

The literature on cardiac malpositions is replete with an arcane vocabulary that often confounds rather than clarifies. Terms have been fully abbreviated, minimally abbreviated, or unabbreviated. In this chapter, unabbreviated terms are used because they are accessible to the widest audience.16

Definitions and terminology*

Situs Solitus

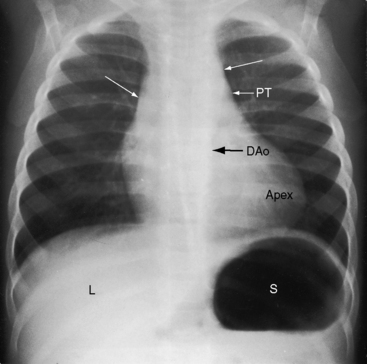

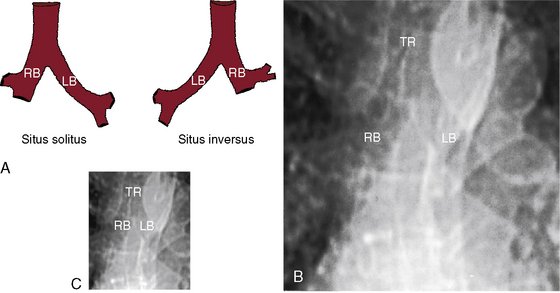

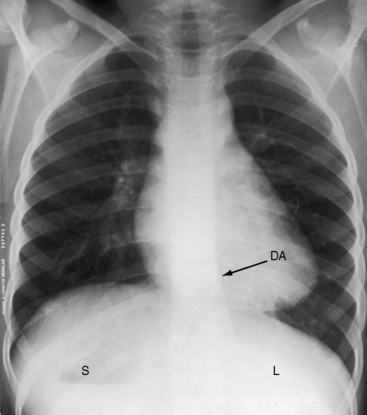

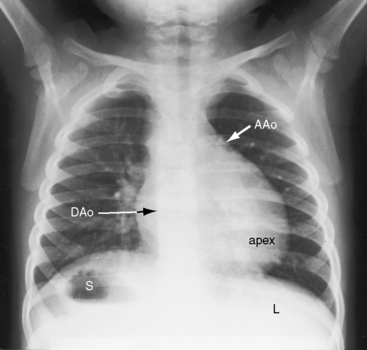

Because atrial situs and abdominal situs are usually concordant, atrial situs solitus can be inferred at the bedside with percussion of a left-sided stomach, a right-sided liver, and a left-sided heart. The chest x-ray confirms the positions of the stomach, liver, and heart (see Figure 3-1) and discloses bronchial morphology, which is a reliable predictor of atrial situs.19 A morphologic right bronchus is relatively short and straight, whereas a morphologic left bronchus is relatively long and curved (Figure 3-5). A morphologic right bronchus is concordant with a trilobed morphologic right lung, and a morphologic left bronchus is concordant with a bilobed morphologic left lung. The chest x-ray establishes the direction of the base to apex axis, which points to the left because the straight heart tube of the embryo initially bends to the right (d-loop) and then pivots to the left until the ventricular portion comes to occupy its normal left thoracic position (see Figure 3-1).9,20 The relative levels of the two hemidiaphragms are determined by the location of the cardiac apex, not by the location of the liver, so the left hemidiaphragm is normally lower than the right hemidiaphragm.21 Thoracoabdominal discordance is represented by thoracic situs solitus, a left thoracic heart, and abdominal situs inversus (Figure 3-6)22,23 or by thoracic situs inversus, a right thoracic heart (dextrocardia), and abdominal situs solitus.

The next step in the systematic analysis concerns the great arteries. The chest x-ray provides information on the spatial relationships of aorta and pulmonary trunk and on ventriculoarterial alignments. In situs solitus with atrioventricular and ventriculo/great arterial concordance, the ascending aorta forms a convex shadow at the right basal aspect of the cardiac silhouette, the aortic arch forms a left basal knuckle below which lies the slightly convex main pulmonary artery segment, and the descending thoracic aorta runs parallel to the left border of the vertebral column (see Figure 3-1).

Malpositions

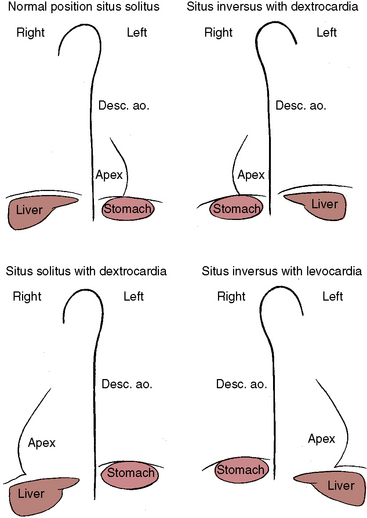

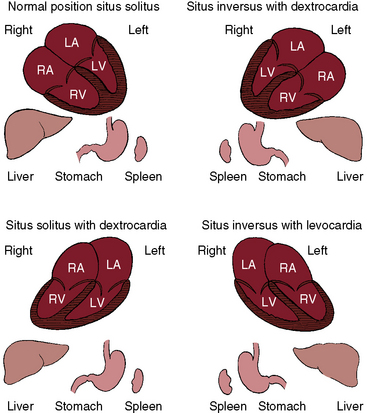

Three major cardiac malpositions occur in the presence of right/left asymmetry (Figures 3-7 and 3-8): (1) visceroatrial situs inversus with dextrocardia; (2) visceroatrial situs solitus with dextrocardia; and (3) visceroatrial situs inversus with levocardia. Mesocardia, a midline heart, is sometimes regarded as a fourth malposition. A midline heart in situs solitus with a d-bulboventricular loop is a variation of normal, but a midline heart with visceroatrial situs inversus and an l-bulboventricular loop occurs with major congenital malformations.18

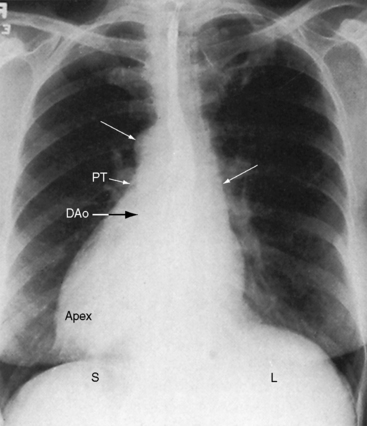

Situs Inversus with Dextrocardia

The incidence rate in the general population is estimated at 1/8000 to 1/25,000.24 The heart and the thoracic and abdominal viscera are mirror images of normal (see Figure 3-2).25 The bronchi are inverted (see Figure 3-5A), with the morphologic right bronchus concordant with the morphologic right atrium and the trilobed lung and with the morphologic left bronchus concordant with the morphologic left atrium and the bilobed lung (see Figure 3-5). The heart is right-sided, and the right hemidiaphragm is lower than the left hemidiaphragm (see Figure 3-2). The descending aorta is on the right; the ascending aorta, aortic knuckle, and pulmonary trunk are in their mirror image positions; and the anatomic right ventricle lies to the left of the anatomic left ventricle (l-bulboventricular loop), which is normal for situs inversus just as a d-bulboventricular loop is normal for situs solitus.

Situs Solitus with Dextrocardia

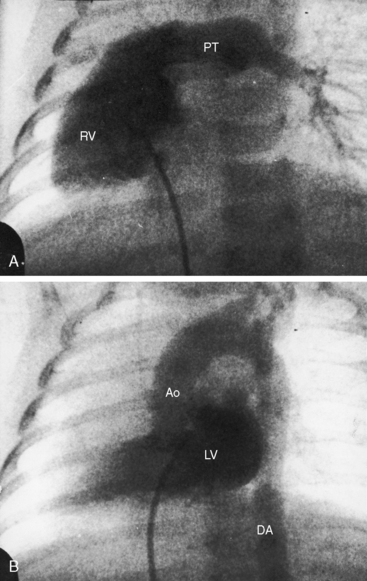

The lungs and abdominal viscera are situs solitus, but the heart is right thoracic (dextrocardia) (Figures 3-7 through 3-10).25 The ascending aorta and aortic knuckle occupy their normal positions and the descending aorta runs its normal course along the left vertebral border (see Figure 3-9), but the major cardiac shadow lies to the right of midline (dextrocardia), the base to apex axis points to the right, and the right hemidiaphragm is lower than the left hemidiaphragm (see Figure 3-9). In the type of situs solitus with dextrocardia shown in Figure 3-9, the anatomic right ventricle lies to the right of the anatomic left ventricle (d-loop) because the straight heart tube of the embryo initially bends in a rightward direction (d-loop) but then fails to pivot into the left chest. Varying degrees of incomplete pivoting determine the degree to which the ventricular portion of the heart lies to the right of midline (see Figure 3-10).

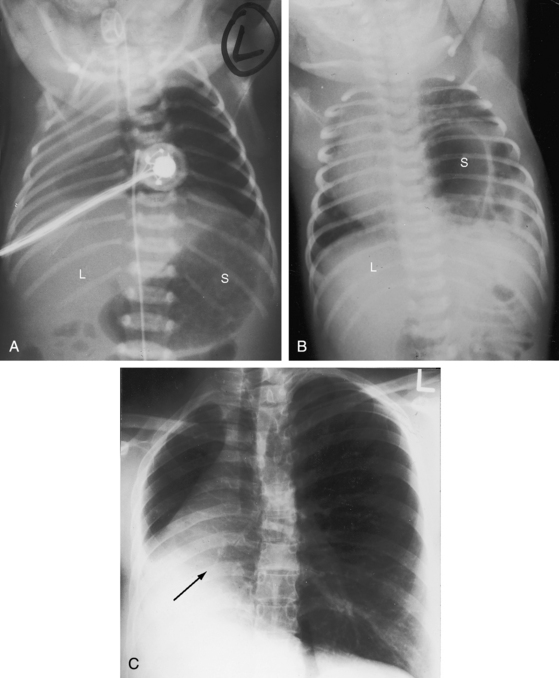

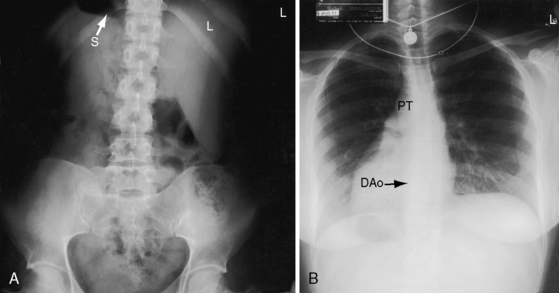

Situs Inversus with Levocardia

The defining characteristics of this malposition are situs inversus of thoracic and abdominal viscera in the presence of a left thoracic heart (levocardia; Figures 3-7 and 3-11). The left hemidiaphragm is lower than the right hemidiaphragm because the apex is on the left (see Figure 3-11). Inversion of the bronchi (see Figure 3-5A) coincides with inversion of the atria and lungs. The stomach is on the right, and the liver is on the left (abdominal situs inversus; see Figure 3-11). The major cardiac mass lies in the left chest for one of two morphogenetic reasons. First, an embryonic l-loop, which is concordant for situs inversus, fails to pivot into the right side of the chest. Second, an embryonic d-loop, which is discordant for situs inversus, fails to pivot into the left side of the chest. When a d-loop in situs inversus is associated with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (ventricular inversion), the ascending aorta forms a smooth shadow at the left basal aspect of the heart (see Figure 3-11).

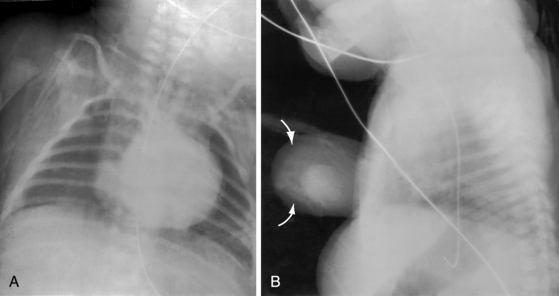

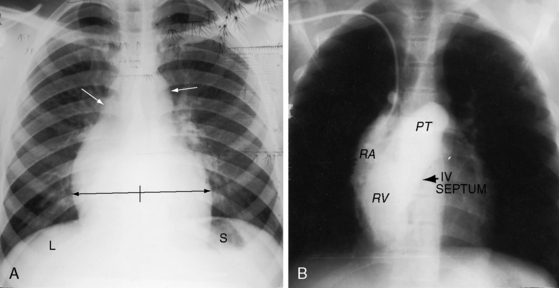

Midline Heart (Mesocardia)

The example shown in Figure 3-12 is a midline cardiac position in the presence of thoracic and abdominal situs solitus. The cardiac silhouette extends equally to the right and left of midline (Figure 3-12A). A d-bulboventricular loop stops in the midline as it pivots to the left (Figure 3-12B).18,26 Much less commonly, mesocardia is associated with situs inversus and an l-loop that stops in the midline as it incompletely pivots to the right.18,26

In brief, two varieties of right-thoracic hearts exist (see Figures 3-7 and 3-8): namely, situs inversus with dextrocardia and situs solitus with dextrocardia. And two varieties of left-thoracic hearts exist: namely, situs solitus with levocardia (normal) and situs inversus with levocardia. A midline heart (mesocardia) is exceptional but occurs either in situs solitus or rarely in situs inversus. Once the cardiac malposition has been defined, clinical assessment turns to the presence and type of associated congenital heart disease.

Situs inversus with dextrocardia (complete situs inversus, mirror image dextrocardia; see Figure 3-2) usually occurs without coexisting congenital heart disease. Isolated atrial inversion is rare.27 Situs solitus with dextrocardia is only occasionally associated with a structurally normal heart (see Figures 3-9 and 3-10); left-to-right shunts at atrial level or ventricular level usually coexist. When situs solitus with dextrocardia occurs with a bulboventricular loop that initially bends to the left and then pivots to the right (where an l-loop belongs),18 ventricular inversion, ventricular septal defect, and obstruction to venous ventricular outflow usually coexist.13,18,28

Situs inversus with levocardia is consistently associated with coexisting congenital heart disease (see Figure 3-11),18 whether the left thoracic heart results from a discordant d-loop that pivots into the left hemithorax or from a concordant l-loop that fails to pivot into the right hemithorax. A discordant d-loop in situs inversus results in ventricular inversion, as does a discordant l-loop in situs solitus.18 Coexisting congenital heart disease is invariable and complex but occurs without prevailing patterns.13,18

A midline cardiac position (mesocardia) occurs in situs solitus (see Figure 3-12) or in situs inversus.18,26 If the bulboventricular loop is discordant, ventricular inversion coexists.

History

Situs inversus with dextrocardia and a structurally normal heart is usually discovered by chance in a chest x-ray, which is often considered normal because the film is inadvertently reversed when first read. A tendency for left handedness in complete situs inversus is reported,1 but Matthew Baillie2 wrote: “The person seems to have used his right hand in preference to his left … which was readily discovered by the greater bulk and hardness of that hand as well as the greater fleshiness of the arm.” Baillie’s conclusion has been confirmed.29

Investigations of the human brain, which is asymmetric in both structure and function, are important.29 The developmental factors that determine functional asymmetry of the brain independently recognize laterality (asymmetry) in visceral situs.29 Developmental factors that determine anatomic asymmetry of the brain are distinct from those that determine visceral asymmetry and lateralization of language.29

Situs inversus with dextrocardia is the malposition most likely to occur with an otherwise structurally normal heart and with normal longevity. Symptoms caused by coexisting acquired cardiac or noncardiac disease may lead to the discovery of hitherto unsuspected situs inversus. The pain of ischemic heart disease is located in the right anterior chest with radiation to the right shoulder and right arm. The pain of appendicitis is referred to the left lower quadrant,30 and the pain of biliary colic presents in the left upper quadrant (Figure 3-13).

In 1933, Kartagener31 called attention to the association of sinusitis, bronchiectasis, and situs inversus, a combination subsequently called Kartagener’s syndrome or triad.32 In the first English-language publication of the syndrome (1937), as many as one fifth of patients with situs inversus had bronchiectasis, underscoring that the association was not fortuitous.33 In 1986, a blinded controlled study of cilia ultrastructure in Kartagener’s syndrome found a widespread inherited ciliary disorder34 that included the upper and lower respiratory tracts (bronchitis, bronchiectasis, sinusitis)32 and the testis (immobile sperm, male infertility).35,36 Situs inversus is common in infertile men, an observation that contributed to the identification of a generalized disorder of ciliary motility.36 Respiratory symptoms are a significant part of the history and may lead to the discovery of situs inversus. Familial situs inversus has been reported,37 and Kartagener’s syndrome is sometimes familial.34 One family of six siblings included two cases of Kartagener’s syndrome and two cases of isolated bronchiectasis.

Situs solitus with dextrocardia occasionally occurs without coexisting congenital heart disease and escapes recognition. A routine chest x-ray may provide the first evidence (see Figure 3-10). As a rule, accompanying congenital cardiac malformations bring the patient to medical attention. Situs inversus with levocardia (see Figure 3-11) invariably occurs with coexisting congenital heart disease that leads to the discovery of the cardiac malposition.

Physical Appearance, Arterial Pulse, and Jugular Venous Pulse

These features are determined by coexisting congenital heart disease rather than the cardiac malposition. The left testicle in the healthy upright male is lower than the right testicle, whereas the opposite is the case in situs inversus. Poland’s syndrome, which is characterized by the absence of a pectoralis major muscle (usually right-sided), ipsilateral syndactyly, brachydactyly, and hypoplasia of a hand, (see Chapter 15, Figure 15-16) has been reported with situs solitus and dextrocardia38; and Goldenhar’s syndrome (oculoauricular vertebral dysplasia, hemifacial microsomia) has been reported with complete situs inversus.39

Percussion and Palpation

A right anterior chest bulge with asymmetry arouses suspicion of dextrocardia. Percussion and palpation are useful in the clinical recognition of cardiac malpositions because these physical signs are influenced by the malposition per se and establish the right or left thoracic location of the heart and the abdominal location of hepatic dullness and gastric tympany. If the stomach is not sufficiently air-filled to generate a tympanitic percussion note, a carbonated beverage or deliberate aerophagia (an infant can suck an empty bottle) solves the problem. Percussion begins over the sternum and then is used to compare left and right parasternal sites. The side of major cardiac dullness is more accurately established with percussion with the patient turned moderately to the left and then moderately to the right. The heart tends to fall to the side toward which the base to apex axis points. Situs inversus with dextrocardia is characterized by gastric tympany on the right, hepatic dullness on the left, and cardiac dullness on the right (see Figures 3-2 and 3-7). Situs solitus with dextrocardia is characterized by normal locations of gastric tympany and hepatic dullness and by cardiac dullness on the right (see Figures 3-7 and 3-10). Situs inversus with levocardia is the converse of situs solitus with dextrocardia (see Figures 3-7 and 3-11).

Palpation is undertaken with the patient supine and then in both left and right lateral decubitus positions. The normal situs solitus heart (see Figure 3-1) is represented by a morphologic left ventricle that occupies the apex and a morphologic right ventricle that underlies the lower left sternal border.40 Situs inversus with dextrocardia (see Figure 3-2) is represented by a morphologic left ventricle that occupies the apex in the right hemithorax and a morphologic right ventricle that underlies the lower right sternal border. Situs solitus with dextrocardia is represented by a right thoracic apical low-pressure morphologic right ventricle that retracts and a high-pressure systemic morphologic left ventricle that generates outward systolic movement adjacent to the lower right sternal border (see Figures 3-9 and 3-10). Situs inversus with levocardia and l-bulboventricular loop is represented by a left thoracic apical low-pressure morphologic right ventricle that retracts and a high-pressure systemic morphologic left ventricle that generates outward systolic movement adjacent to the lower left sternal border (see Figures 3-11).

Auscultation

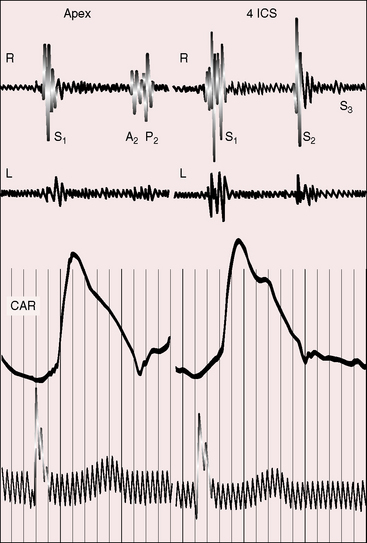

The relative prominence of auscultatory events should be compared in the left and right anterior hemithorax, more specifically along the left and right sternal borders and at the apices (Figure 3-14). The stethoscope should alternate from one side to the other for comparison of analogous right and left thoracic sites. With dextrocardia, the first and second heart sounds are louder in the right anterior chest (see Figure 3-14); splitting of the second sound in the second right intercostal space is a feature of dextrocardia just as splitting of the second heart sound in the second left interspace is a feature of a left thoracic heart. In situs solitus with dextrocardia and a d-bulboventricular loop (see Figures 3-9 and 3-10), the position of the pulmonary valve results in splitting of the second sound in the second right interspace and the anterior position of the aorta results in amplification of the aortic component (Figure 3-15). In situs inversus with levocardia, splitting of the second sound is more prominent in the second left interspace.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree