Classification

General

The classification of lung carcinomas is presented in

Table 72.1, which conforms to the latest World Health Organization approach.

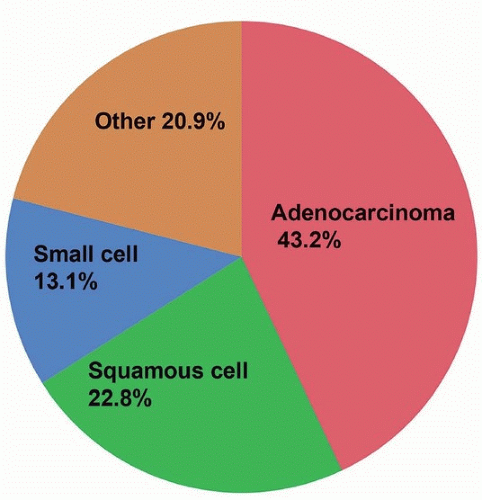

1The most frequent subtype of lung carcinoma is adenocarcinoma, which is steadily increasing in proportion to other tumors (

Fig. 72.1). Currently, it is more than twice as common in women as small cell or squamous cell carcinomas, which are about equal in incidence. In men, squamous carcinomas are still relatively frequent, accounting for 30% of tumors, but ten percentage points behind adenocarcinoma.

There has been a marked shift in frequency of histologic types. In the latter part of the last century, squamous carcinomas were more than twice as common in men than adenocarcinomas, and lung cancers were relatively infrequent in women. Today, there are few gender differences in rates of lung cancer by type, except that squamous carcinomas are relatively infrequent in women.

2

Incidence

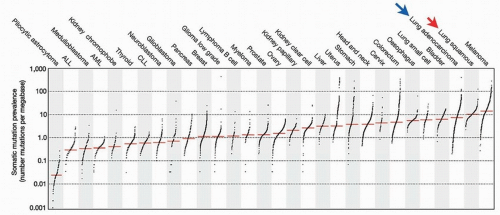

Lung cancer is one of the most common tumors and has a high rate of mortality. There are ˜55/100,000 new cases annually, with 45/100,000 deaths yearly (http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html). The rate of lung cancer diagnosis and deaths is on the decline, from a peak of 70/100,000 and 60/100,000 per year, respectively, in the early 1990s.

Adenocarcinomas

Adenocarcinomas are classified on the basis of cell type, namely nonmucinous, derived from pneumocyte-like cells, which generally express TTF-1, and mucinous adenocarcinomas. Nonmucinous adenocarcinomas are typically classified by growth pattern. These include acinar (the term used for tubular or glandular growth), papillary, micropapillary, and solid growth patterns.

One pattern that is included in the classification is the lepidic, or in situ growth pattern, which sets lung carcinomas apart from classification of other cancers. A previous term that came to designate “in situ” carcinoma without invasion, namely, “bronchioloalveolar carcinoma,” has been abandoned in favor of the term “adenocarcinoma in situ.”

Adenocarcinomas with predominantly in situ growth are now designated “lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma” or “minimally invasive adenocarcinoma,” if the invasive component is <5 mm (see

Chapter 74 for details).

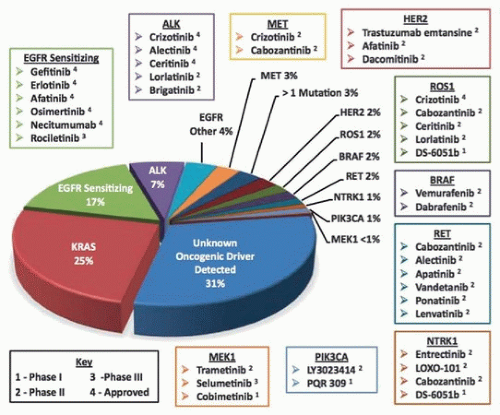

Mucinous adenocarcinomas of the lung are heterogeneous and have growth patterns that generally mimic that of nonmucinous tumors. They have a propensity for in situ growth and multiplicity and may demonstrate features that resemble colloid carcinomas of the colon and appendix, in which case colonic markers may be expressed. Their molecular profile is distinct from that of nonmucinous carcinoma and is characterized by

KRAS mutations (see

Chapter 76).

Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Squamous cell carcinomas are similar to their counterparts in other organ sites and are very strongly associated with cigarette smoking. “Basaloid” carcinomas were previously separated from conventional squamous carcinomas, because of their relatively poor prognosis. However, they are now considered a variant of squamous carcinoma. In the WHO classification, lymphoepithelial-like carcinomas have a separate classification. In this book, they are considered in the chapter on squamous carcinoma, as they often express similar markers immunohistochemically.

Small Cell Carcinomas

In the most recent classification of lung tumors, small cell carcinomas are considered in the same overall framework as large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas and carcinoid tumors (see

Chapter 79). Like squamous carcinomas, they are strongly associated with smoking. Their histologic features and biologic behavior are well known and studied. Occasionally, adenocarcinomas with EGFR mutations (that usually occur in nonsmokers) may acquire resistance to EGFR TKI drugs and recur with endocrine differentiation and resemble small cell carcinomas. Rarely, small cell carcinomas arise de novo in patients who have never smoked.

Neuroendocrine Carcinomas

In the lung, the term “carcinoid tumor” is still used for low-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas. The distinction between carcinoid and atypical carcinoid tumor is still made based on light microscopic features (i.e., mitotic counting).

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is now relatively firmly established as a specific clinicopathologic entity that clinically behaves similar to small cell carcinoma, but has a different histologic appearance. It is defined by both histologic and immunohistochemical features.

Large Cell Carcinomas

The last relatively large group of lung cancers that is controversial and not well defined is that of “large cell carcinoma.” Its use as term is no longer applied to large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and is also not applied to small biopsy samples (see

Chapter 82). Currently, it denotes a poorly differentiated tumor without small cell, neuroendocrine, or sarcomatoid features that is presumably either a primitive squamous or adenocarcinoma. Molecular studies have demonstrated that most “large cell carcinomas” are likely poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas that do not express classic adenocarcinoma markers.

Combined Carcinomas

Another area of potential difficulty is terminology for carcinomas with varied histologic types. The most common combined carcinoma is adenosquamous carcinoma (Chapter 83), followed by combined small cell carcinoma (with adeno- or squamous carcinoma). These diagnoses are generally straightforward with adequate tissue sampling, unless the squamous component lacks keratinization and is poorly differentiated. Combined large cell neuroendocrine with small cell carcinoma is generally considered small cell carcinoma for treatment purposes. Areas of undifferentiated, nonsarcomatoid tumors (large cell carcinoma) are usually not separated into a combined category.

Sarcomatoid Carcinomas

The classification of carcinomas with spindling involves poorly differentiated tumors, spans a large range of histologic patterns, and rests on convention. In this book, we have adhered fairly closely to the WHO (Chapter 85). Pleomorphic carcinoma is applied to combined spindle and adeno- or squamous carcinoma. Spindle cell carcinoma is reserved for tumors that lack differentiated areas and carcinosarcoma to combined tumors with heterologous elements. Highly pleomorphic tumors with giant cells are given the designation “giant cell carcinoma” and often have areas of other high-grade histology.