Calf Vein Thrombosis (or Tibial DVT)

ELNA MASUDA

Presentation

Case 1 A 76-year-old male patient with active colon cancer presents with severe left leg calf pain and swelling for 5 days. He has no shortness of breath, chest pain, or hemoptysis. No prior history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary emboli (PE).

Case 2 A 50-year-old female with mild right calf pain and swelling 1 week after undergoing right knee arthroscopy. She has no chest symptoms, and her past history is negative for prior DVT/PE. She has chronic active hematuria from nephrolithiasis and required blood transfusions 1 week ago. She has been compliant with all her doctor appointments and remains ambulatory and active.

Differential Diagnosis

Leg pain and swelling during the postoperative period should prompt early investigation of DVT which could involve the inferior vena cava (IVC), iliac, femoral, popliteal, and/or calf veins. For isolated calf DVT, which is a likely cause, treatment with anticoagulation versus duplex surveillance depends on clinical risk factors, including the severity of symptoms and contributing risk factors for clot propagation. It is imperative that the physician recognizes and treats the blood clot sufficiently to avoid potential propagation, recurrence, and serious consequences of PE. The differential diagnosis should also include other less serious but common diagnoses below the knee including hematoma, ruptured Baker’s cyst, and cellulitis.

With calf vein thrombosis, the clot may involve either one or both paired “axial veins”: posterior tibial, peroneal, and anterior tibial veins. Other calf vein thrombi that qualify as deep vein thrombosis are clots involving the “muscular veins,” which include soleal and gastrocnemius veins as they drain the calf muscles.

Notably, when isolated calf DVT (CDVT) is reported, they usually involve the posterior tibial and/or peroneal and rarely if ever involve the anterior tibial vein alone. Therefore, many vascular laboratories elect not to include the anterior tibial in the initial test for DVT below the knee, and the Accreditation Laboratories do not require initial scanning of the anterior tibial vein.

The diagnosis of hematoma is usually associated with a history of trauma. Ruptured Baker’s cyst can mimic DVT and is frequently identified by duplex ultrasound scanning, MRI, or CT.

Workup

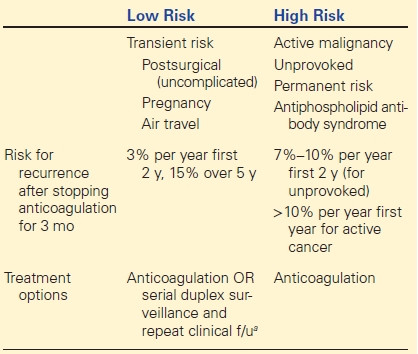

Clinical suspicion should always be high in any postoperative patient with leg pain and/or swelling. A thorough history and physical exam should include a past history of previous DVT or PE, which would represent a significant risk for recurrence. A complete history should include examining for risk factors listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Stratifying Treatment Based on Clinical Risks Factors for DVT

aDuplex surveillance reserved for those reliable for follow-up and minimal symptoms.

If the clinical suspicion for DVT is moderate to high, there should be a low threshold to proceed directly to ultrasound testing by either compression ultrasound or color flow duplex scanning. Although compression ultrasound with gray scale alone is sufficient in most cases particularly in proximal or femoral popliteal DVT, the addition of color to the duplex scanning improves resolution of calf veins. If DVT is identified, then the opposite leg from the index DVT limb should be scanned because of approximately 20% chance of finding a DVT in the opposite limb.

d-Dimer levels can be useful in the outpatient setting and if the clinical suspicion for DVT is low. Positive d-Dimer has limited value since it lacks specificity and can be elevated by inflammatory states, cancers, advanced age, infection, and pregnancy. A negative d-Dimer is very useful for excluding an acute DVT, particularly in a low-risk clinical scenario. In the current scenario presented, d-Dimer would be of little value given the high clinical risk for DVT.

Diagnosis and Treatment

All patients with calf DVT must be clinically examined for symptoms and signs of PE such as dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, hemoptysis, and tachycardia that should lead to proper workup with CT angiogram of the chest. If PE is identified, all must undergo standard anticoagulation for at least 3 to 6 months.

Once PE have been clinically excluded, treatment choices for calf DVT include standard anticoagulation for 3 to 6 months or serial duplex ultrasound surveillance with repeat clinic follow-up. Several factors should be considered in determining best treatment strategy for the patient. This includes clinical risk category (Table 1), degree of symptoms, logistics of treatment, dependability of follow-up, and patient preference.

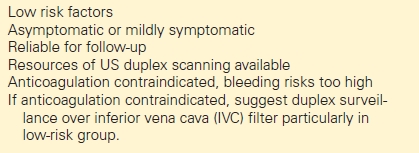

Patients should be stratified into low or high risk for propagation based on presenting clinical risk factors.

High-risk patients for clot propagation and recurrence should be treated with anticoagulation and not duplex surveillance. These include those with active malignancy, unprovoked DVT, antiphospholipid syndrome, large clot burden such as bilateral calf vein DVT, those with prior history of DVT, and/or severe symptoms of pain and swelling. Patients with severe pain or swelling may benefit from heparin therapy in addition to its anticoagulant effect, by its anti-inflammatory effects, and symptomatic relief (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Suggested Indications for Duplex Scan Surveillance and Repeat Clinical Follow-Up