Figure 23.1

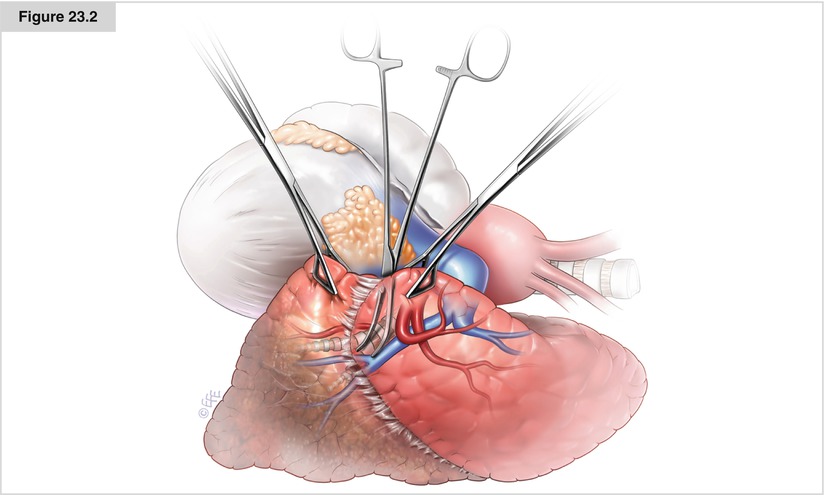

A lateral thoracotomy incision is made, and the thorax is entered through the sixth intercostal space for lower lobe and the fifth intercostal space for middle or upper lobe bronchiectasis. The parietal pleura is mildly or moderately thickened and attached to the lungs and chest wall. An extrapleural area is created first by blunt dissection, and the intercostal space is enlarged by using two rib spreaders for better exposure. The parietal pleura is held by two long clamps; the lung is palpated underneath, and the pleura is opened carefully with a scissor. The index finger is advanced through the hole in the parietal pleura to detach the visceral pleura gently, without injuring the lung. Subsequently, the parietal pleura is cut with the scissor to sufficiently expose the lobes. The diseased lobe becomes smaller and attaches firmly to the diaphragm and moderately to the chest wall, pericardium, aorta, and other lobe(s), depending on its anatomic location (lower or upper lobe and right or left side). In the most commonly observed location, the left lower lobe, the release of the bronchiectatic lobe starts from the surface of the descending aorta after the thoracic wall attachment is separated by blunt and sharp dissection. Generally, the aortic adventitia prevents firm invasive adhesions, making blunt separation of the lobe by hand safe. Dissection is performed by positioning the backside of the hand over the aorta while two or three fingers create a cleavage under the lobe and over the aorta. The thumb feels the fingers where the lobe attaches to the chest wall lateral to the aorta, and this attachment is released mainly by finger dissection and partly by sharp dissection to the diaphragm. The inferior surface of the lung is firmly attached to the diaphragm so that a border between the lung and diaphragm cannot be recognized easily. Therefore, dissection by the fingers from below is preferred to avoid tears in the muscle of the diaphragm. Surface bleeding is common during aortic and diaphragmatic dissection and controlled best by warm towel compressions. Releasing from the pericardium and fatty tissue is performed mainly by the energy-based ligation method or electrocautery

Figure 23.2

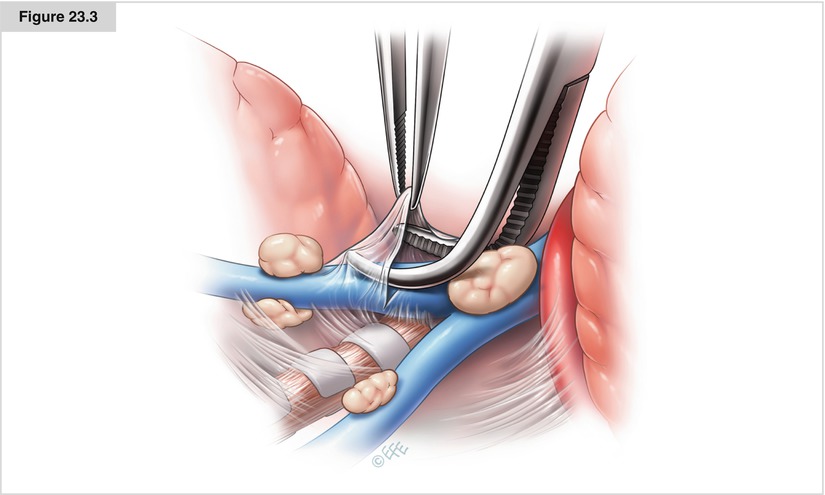

When there is a firm symphysis between the lobes as a result of chronic inflammation, a sharp separation process may cause tears in the healthy lung that are associated with prolonged postoperative air leak. Therefore, a 3- to 4-mm tunnel is created first by a blunt, pointed, long-curved dissector from just inferior to the superior pulmonary vein to the lateral side of the lower lobe bronchus. Then, one arm of a linear stapler is passed through this hole, the lobes are grasped with lung clamps, the other foot of the stapler is placed over the lung on the border between the fibrotic and healthy lobes, and stapling is completed to separate the lobes

Figure 23.3

Because large and firm lymph nodes generally are found in the fissure over the interlobar pulmonary artery, ligating the pulmonary vein first may cause distension of the lobe during the time-consuming arterial dissection. Therefore, vascular dissection preferentially starts from the arterial side. The main right or left pulmonary artery is encircled with tape to help control any bleeding that may occur during lymph node dissection over the artery in the fissure. Clearing the lymph nodes over the superior segmental artery helps the surgeon find the correct cleavage of the entire artery in the fissure. If a tunnel can be created between the lymph node and the artery by opening the prevascular sheet, the lymph node can be resected and the artery ligated or stapled safely. In the presence of highly invasive lymph nodes, it is not possible to secure the artery safely. In these situations, the pulmonary vein is ligated first, then the bronchus is cut, and the remaining bundle containing the artery and lymph nodes is ligated or stapled. The bronchus is closed by hand suturing or a stapling device. (See also Chap. 17 for technical details on bronchial and vascular closures.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree