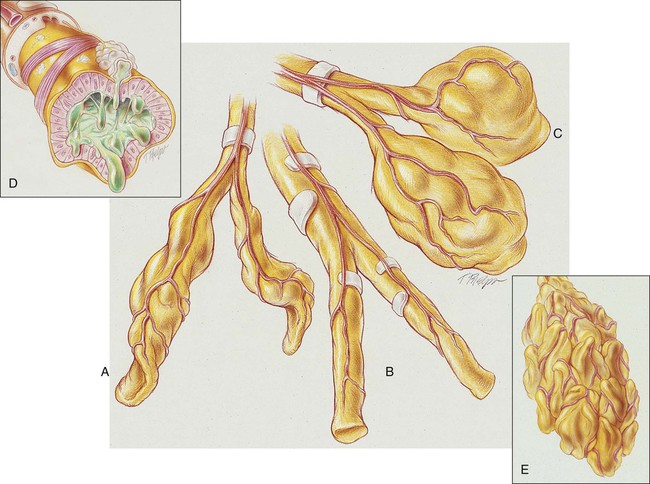

After reading this chapter, you will be able to: • Describe the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with bronchiectasis, including the following: • Varicose (fusiform) form of bronchiectasis • Cylindrical (tubular) form of bronchiectasis • Cystic (saccular) form of bronchiectasis • Differentiate between the following possible types of bronchiectasis: • Describe the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with bronchiectasis. • Describe the general management of bronchiectasis. • Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study. • Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve. In cylindrical (tubular) bronchiectasis, the bronchi are dilated and rigid and have regular outlines similar to a tube. X-ray examination shows that the dilated bronchi fail to taper for 6 to 10 generations and then appear to end abruptly because of mucous obstruction (see Figure 13-1, B). In cystic (saccular) bronchiectasis, the bronchi progressively increase in diameter until they end in large, cystlike sacs in the lung parenchyma. This form of bronchiectasis causes the greatest damage to the tracheobronchial tree. The bronchial walls become composed of fibrous tissue alone—cartilage, elastic tissue, and smooth muscle are all absent (see Figure 13-1, C). The following are the major pathologic or structural changes associated with bronchiectasis:

Bronchiectasis

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

Cylindrical Bronchiectasis (Tubular Bronchiectasis)

Cystic Bronchiectasis (Saccular Bronchiectasis)