Chapter 37 Breast Reconstruction

History

Since approximately 1970, many advances in reconstructive surgery have occurred and been applied to breast reconstruction. The development of breast implants was the first of these revolutions. In 1963, the silicone breast implant was introduced for breast augmentation and was quickly adopted for breast reconstruction. In 1963, Cronin and Gerow1 presented a series of patients who received implants for reconstruction of mastectomy defects. For the first time, the plastic surgeon had a procedure that could simulate the missing breast without the need for multiple procedures and a prolonged treatment course. In many ways, it was the simplicity and safety of breast implants that ignited interest in breast reconstruction. By the later 1970s, reconstruction was being performed immediately after breast ablation.2–4

The development of muscle, musculocutaneous, and fasciocutaneous flaps and microsurgical transplantation has had a tremendous impact on breast reconstruction. The ideal material to reconstruct any defect is similar to tissue. Until the early 1970s, such tissue was available only in limited quantities for breast reconstruction. The landmark work by Manchot5 on vascular territories of the body was rediscovered, and surgeons were then able to exploit this basic knowledge to design flaps based on the axial patterns of named blood vessels. These technical developments allowed surgeons to rearrange tissues reliably and more precisely reconstruct all types of defects, including those of the breast.6

Patient Selection

Women have a number of reasons for choosing to undergo breast reconstruction, including no need for an external prosthesis, fewer limitations with regard to clothing, regaining femininity, and feeling whole again. Others choose not to undergo reconstruction because they feel too old for the procedure or are afraid of complications.7,8 Given the myriad of options in breast reconstruction, the surgery should be tailored to the patient’s wishes as well as her underlying health. There are a small number of relative contraindications to breast reconstruction. Extreme age, severe cardiovascular disease or other comorbidities, extreme obesity, and advanced breast disease are possible reasons why breast reconstruction may not be reasonable.

Often, women are faced with the choice, in early disease, of breast conservation therapy (BCT) versus mastectomy. Studies have shown equivalent survival outcomes when comparing the modalities of BCT with radiation and mastectomy. These decisions are often made in conjunction with the ablative surgeon. Patient satisfaction with these two modalities is varied. Pusic and colleagues9 have surveyed women who underwent lumpectomy/XRT, mastectomy, and mastectomy with reconstruction. Similar to Reaby’s report,7 women who chose reconstruction were younger, white, and more educated. Interestingly, comfort with nudity was much lower in the mastectomy-alone group and quality of life varied with age. Younger women (<55 years) were least happy with mastectomy alone, whereas those older than 55 years were least satisfied with lumpectomy. Ultimately, the choice is that of the breast cancer patient and must be individualized.

Similarly, BCT is also evolving. It is now possible to minimize the effects of radiation on the breast after lumpectomy via oncoplastic techniques. These include breast reduction strategies to obliterate the dead space of lumpectomy–segmental mastectomy and to counteract the contractile forces seen after radiation therapy. These techniques are used by a breast surgeon or plastic surgeon. All these techniques will be discussed further.10,11

Timing

The timing of breast reconstruction after mastectomy has progressed from delayed to immediate because of advances and refinements in breast reconstructive techniques and recognition of beneficial psychological effects.7,9,10,12 Because studies have shown a psychological benefit, cost-effectiveness, cosmetic advantage, and no increased risk for complications or oncologic risk with immediate breast reconstruction, it has become the preferred timing of reconstruction. In 1990, the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons reported that members performed 38% immediate versus 62% delayed reconstructions. In a more recent study, 75% of reconstructions were performed immediately.13

Because most local tumor recurrences are in the skin and/or subcutaneous adipose tissue or in the axilla, there are few reasons to delay reconstruction. Therefore, immediate reconstruction has become commonplace in America.14 It affords psychological benefits to women and is the opportune time to preserve the normal footplate of the breast—most importantly, the inframammary fold. This can be more difficult in a delayed reconstruction setting. Skin flaps are also more pliable in the immediate setting. Currently, most women with stage I or II cancer are candidates for immediate reconstruction. There are caveats to this with certain chemotherapeutic agents and the need for adjuvant radiotherapy, in which immediate reconstruction is not possible. These can interfere with postoperative healing and aesthetic outcome, respectively.

Procedure Selection and Surgical Planning

The options for surgical breast reconstruction are varied and include partial and total reconstruction. Total breast reconstruction involves two common modalities, the use of an expander or implant, autologous tissue, and some combination of the two. Any of these procedures must not delay adjuvant cancer therapies. The most common procedures performed are the following (Box 37-1):

Implant-Based Reconstructions

Implant reconstructions are performed in those women who have a reasonable amount of good-quality skin after mastectomy, enough to cover an implant completely and provide a natural shape. They are advantageous in that they are relatively quick procedures, with minimal morbidity to the patient. Implant reconstruction is best used for a bilateral reconstruction because it is the best opportunity for symmetry. With implant-only reconstructions, it is difficult to mimic the natural ptosis and contour of the contralateral breast, except in the cases of young women with relatively small, youthful-appearing breasts (Box 37-2).

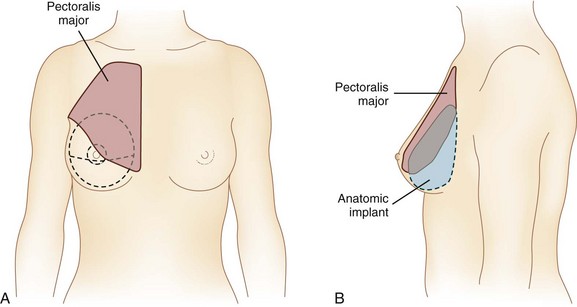

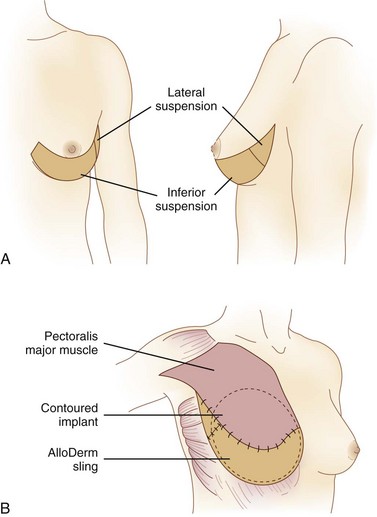

Initially, these reconstructive procedures were performed with placement of the implant in the subcutaneous pocket. This fell out of favor because of visible rippling of the implant beneath a thin layer of skin and a greater complication risk of capsular contracture. Currently, these implants are placed in a submuscular pocket beneath the pectoralis major. Some surgeons provide for full muscle coverage, with the assistance of the serratus anterior and rectus abdominis fascia inferiorly. Others provide coverage of the inferior pole of the implant with bioprosthetic material (e.g., human, porcine, bovine dermal allografts) to help create a natural inframammary fold and contoured reconstruction and provide an additional layer between the implant and inferior mastectomy skin flap. This material is sutured to the pectoralis major muscle superiorly and then inferiorly to the previously marked or designated inframammary fold (Figs. 37-1 and 37-2).13,15,16 Either method helps fix the pectoralis major and keeps it from migrating superiorly, exposing more of the implant.

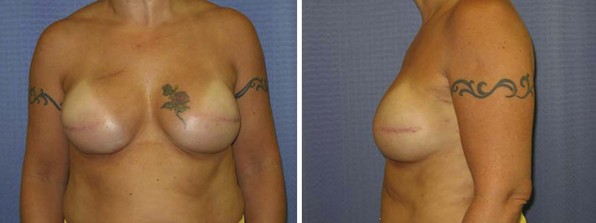

In general, implant-based reconstructions provide for a round-shaped, youthful breast mound without ptosis (Fig. 37-3). Some would refer to this as less natural. It requires multiple clinic visits to provide for expansion and then a subsequent procedure to place the permanent implants, which requires a time commitment from the patient. Over time, implant reconstructions tend to change because of the effects of gravity, the body’s response to foreign objects (capsule formation), and aging of the implants themselves. This occurs linearly with time, so that 86% of women are pleased with their results at 2 years versus 54% at 5 years.17

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree