Bradycardia

Eric D. Good

Krit Jongnarangsin

USUAL CAUSES

Bradycardia is defined as a heart rate less than 60 beats per minute. This traditional rate cutoff is arbitrary, and many asymptomatic people have heart rates below 60 beats per minute who have no cardiac abnormalities (see “sinus bradycardia”). Pathologic causes of bradycardia are diverse and can be divided into intrinsic and extrinsic etiologies: these are listed in Table 19.1. Intrinsic causes of bradycardia may be related to conduction abnormalities of the sinus or atrioventricular (AV) nodes, His-Purkinje system, and atrial or ventricular myocardium. Because the cardiac conduction system is composed of specialized cardiac myocytes, common myocardial diseases such as ischemia, infarction, hypertension, surgical trauma, age-related degeneration, and dilated cardiomyopathies can also result in bradycardia. Less common pathologic causes of bradycardia include infiltrative disorders, collagen vascular diseases, familial conduction-system diseases, and infections such as endocarditis or Lyme disease. Because a portion of the atrioventricular conduction system is a narrow electrical corridor without redundancy, small pathologic lesions can result in profound bradycardia. Occasionally, bradycardia is caused by idiopathic degeneration of the conduction tissue. Bradycardia can also be a result of intentional or unintentional catheter ablation of the sinus node or atrioventricular junction.

Congenital heart block tends to occur in children of women with autoimmune diseases and results from transplacental transfer of maternal anti-Ro or anti-La antibodies or both. Sinus bradycardia may be associated with congenital complete heart block (1).

Extrinsic causes of bradycardia include hypervagotonia, drugs, hypoxemia, central nervous system disease, thyroid disease, and electrolyte abnormalities. Sleep is normally accompanied by marked bradycardia, especially in young patients. Complex partial seizures have also been included among the long list of functional causes of bradycardia (2).

An abnormal increase in vagal tone is responsible for the bradycardia seen during vasodepressor syncope, carotid sinus hypersensitivity, and cough and micturition syncope, although adrenergic withdrawal can also be a factor. Careful identification of reversible causes can lead to prevention of unnecessary therapy. For example, tracheostomy can correct the bradycardia associated with sleep apnea (3).

PRESENTING SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

Patients with bradycardia have a broad spectrum of signs and symptoms. Because symptoms are usually nonspecific, it is important to be as certain as possible that the symptoms are secondary to bradycardia. Patients with persistent bradycardia can have symptoms that progress gradually, such as fatigue, dizziness, or exercise intolerance, or can have symptoms that occur suddenly, such as syncope, congestive heart failure, or cardiac arrest. Patients with paroxysmal bradycardia usually are first seen with palpitations, dizzy spells, presyncope, syncope, or seizures, depending on the escape rhythm and the

degree of cerebral perfusion during the bradycardia. Many patients with bradycardia are asymptomatic.

degree of cerebral perfusion during the bradycardia. Many patients with bradycardia are asymptomatic.

TABLE 19.1. Causes of bradycardia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bradycardia is often accompanied by a bounding pulse and a large pulse pressure. When complete heart block is present, the physical examination can reveal signs of atrioventricular dissociation, such as cannon A waves in the neck veins and variable atrioventricular-valve closure sounds. In affected elderly patients, confusion is occasionally the sole manifestation of bradycardia.

HELPFUL TESTS

Proper characterization of a bradycardia often helps identify the cause. For example, transient atrioventricular block that occurs at the same time as transient sinus slowing is diagnostic of a vagal cause and does not require further evaluation. However, when an intrinsic cause is suspected, further testing is usually warranted, to exclude underlying structural heart disease.

An electrocardiographic recording is necessary to establish a diagnosis of bradycardia. Simple palpation of the pulse can lead to an erroneous diagnosis of bradycardia in the setting of atrial or ventricular bigeminy. A 12-lead electrocardiogram should be obtained for all patients with symptoms suggestive of bradycardia.

For patients with daily symptoms suggestive of bradycardia, an ambulatory Holter monitor can be helpful for characterizing the rhythm. For patients with less-frequent symptoms, a continuous-loop recorder collects data better than does a Holter monitor. Continuous-loop recorders can be worn for several weeks and can be used to transmit a rhythm strip over the phone after a patient has symptoms (4). An implantable loop recorder is also available for patients who have infrequent symptoms but is usually reserved for patients with recurrent, unexplained syncope (5).

A formal exercise-treadmill test can be helpful in establishing a diagnosis of chronotropic incompetence. However, a simple recording of the cardiac rhythm before and immediately after a short walk or stair climbing is often sufficient and saves the expense of formal exercise testing.

Maneuvers or medications that increase the sinus rate, such as ambulation or atropine, are useful tests in the setting of second-degree atrioventricular block. If the atrioventricular block worsens when the sinus rate increases, the conduction block is usually pathologic and related to an intrinsic abnormality of the His-Purkinje system.

Electrophysiologic testing can be useful in the evaluation of patients with symptoms suggestive of bradycardia (6). Measurement of the sinus node recovery time—the time between cessation of rapid atrial pacing and the first spontaneous atrial depolarization from the sinus node—is a useful test of sinus node function. Intracardiac recordings are valuable in patients with atrioventricular block when the surface electrocardiogram is not sufficient to determine the level of block. Intracardiac His-bundle recordings can reveal whether atrioventricular block is at or below the level of the atrioventricular node. If the level of atrioventricular block is below the atrioventricular node, placement of a pacemaker is often indicated. Early studies suggested

that electrophysiologic testing should be performed in patients with bundle-branch block to determine whether the patient is at risk for developing higher-degree atrioventricular block (7). However, the predictive value in this setting is low. Therefore electrophysiologic testing is currently not indicated for the evaluation of asymptomatic patients with isolated bundle-branch block.

that electrophysiologic testing should be performed in patients with bundle-branch block to determine whether the patient is at risk for developing higher-degree atrioventricular block (7). However, the predictive value in this setting is low. Therefore electrophysiologic testing is currently not indicated for the evaluation of asymptomatic patients with isolated bundle-branch block.

Patients with unexplained syncope and bundle-branch block should undergo electrophysiologic testing to exclude inducible ventricular tachycardia before paroxysmal bradycardia is assumed to be the cause of syncope, especially in the setting of left ventricular dysfunction (8).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Bradyarrhythmias can be categorized as those caused by dysfunction of the sinus node and those caused by dysfunction of the atrioventricular conduction system. The characteristics of each bradyarrhythmia are described in the following sections. Proper characterization of the bradyarrhythmia is important because it helps determine the cause, prognosis, and treatment.

Tissues that constitute the cardiac conduction system have the ability to depolarize spontaneously. The intrinsic spontaneous rate of depolarization usually decreases in the anatomic direction of normal impulse propagation. The dominant pacemaker normally arises from within the sinus node complex and suppresses spontaneous depolarization of the distal conduction tissue. During bradycardia, these latent pacemaker cells are unmasked and give rise to the dominant rhythm. Escape beats and rhythms are also described hereafter.

Sinus Node Dysfunction

Abnormal sinus node function can result from abnormal automaticity or from sinus node exit block, and it manifests as sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses, or chronotropic incompetence. Sinus node dysfunction is often referred to as sick sinus syndrome and is the most common indication for pacemaker implantation. Patients with sinus node dysfunction often have concomitant atrial disease, which results in atrial tachyarrhythmias. This common association is referred to as the tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome.

Sinus Bradycardia

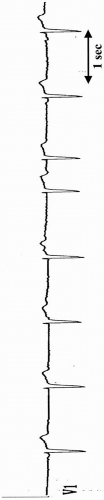

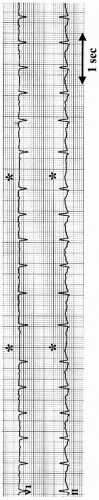

Sinus bradycardia is defined as a sinus rhythm with a rate less than 60 beats per minute (Figs. 19.1 and 19.2). Some authors have argued that sinus rhythm rates as low as 46 beats per minute in men and 51 in women should be considered normal (9). Young patients and trained athletes often have even more marked sinus bradycardia because of elevated vagal tone. Sinus bradycardia is also observed normally during sleep.

Sinus Pause

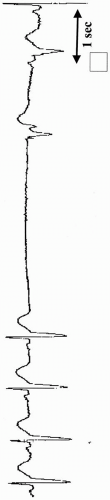

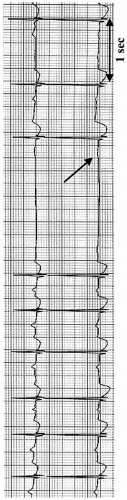

A sinus pause is present when the length of a pause is not a multiple of the baseline sinus-cycle length (Fig. 19.3). In contrast, sinoatrial (SA) exit block is diagnosed when a pause is present and the length of the pause is equal to a multiple of the baseline sinus-cycle length. As with atrioventricular blocks, SA block can be categorized as first-, second-, or third-degree block. First-degree SA block is caused by a delay in transmission of SA depolarization to the atrial tissue and can be diagnosed only with specialized intracardiac recordings. Second-degree SA block is manifested as a sinus pause and results from intermittent failure of conduction from the sinus node to the surrounding atrial muscle. Second-degree SA block can be categorized in the Wenckebach classification system as type I or type II. Type I SA block is manifested as gradual shortening of the sinus-cycle length followed by a pause that is not equal to the preceding PP interval (Fig. 19.4). Type II SA block is characterized by a constant sinus-cycle length followed by a sinus pause that is equal to the preceding PP interval. High-grade SA block is present when the pause is equal to a multiple of the preceding PP interval.

FIGURE 19.1. Rhythm strip from lead V1, showing marked sinus bradycardia. The sinus rate is 27 beats per minute. |

FIGURE 19.3. Two-lead rhythm strip of a sinus pause with an atrial escape beat. Note that the morphologic pattern of the first P wave after the sinus pause differs from the sinus P waves (arrow). |

An excessively long pause is often called sinus arrest and can be caused by third-degree SA exit block or decreased automaticity (Fig. 19.5).

Chronotropic Incompetence

A rate of increase in sinus node firing that is inappropriately slow relative to the level of exertion indicates a condition termed chronotropic incompetence; this is considered to be a relative bradycardia. Several definitions are proposed for chronotropic incompetence, including failure to reach a heart rate that is either 85% of, or two standard deviations below, the age-predicted maximal heart rate (220 beats/min minus years of age). However, patients who have clinically relevant chronotropic incompetence usually demonstrate an obvious inability to increase the heart rate appropriately with activity.

Atrioventricular Conduction Disturbances

Atrioventricular block can occur at the level of the atria, AV node, within the His bundle, or within the Purkinje system distal to the His bundle. Atrioventricular block caused by intraatrial conduction block results when the sinus node impulse does not reach the atrioventricular node, but this is rare. Causes include atrial myopathies, cardiac surgery, heart transplant, and ablation procedures. Atrioventricular block is categorized as first-, second-, or third-degree. Identification of the level and type of block is important, because they are related to the prognosis and therapy.

The atrioventricular conduction system serves to prevent rapid atrial rhythms from conducting to the ventricle on a 1:1 basis. Therefore pathologic atrioventricular block must be distinguished from atrioventricular block that results from normal refractoriness (Fig. 19.6).

First-Degree Atrioventricular Block

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree