Blastomycosis

Presentation

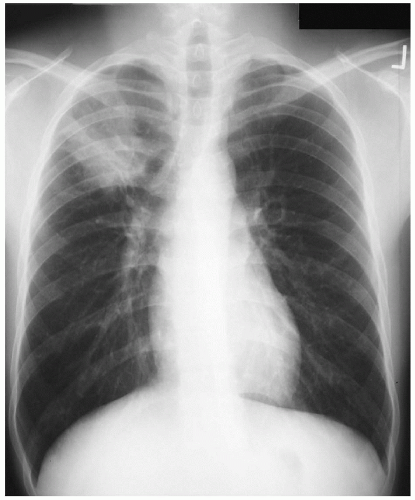

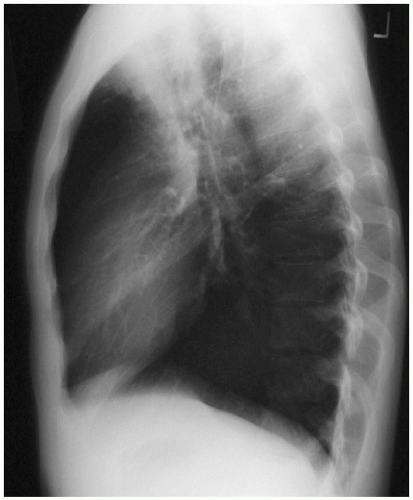

A 24-year-old man is sent to your office by his primary medical physician for recommendations regarding an abnormal chest x-ray. The patient presents with a history of pneumonia, which was treated with several courses of antibiotics without any significant improvement in radiographic findings. The patient’s physical examination is significant for rales over the right upper lung field. He denies any travel except for a camping trip 3 months ago in Mississippi. The patient’s past medical, work, and social history are unremarkable, with no risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Case Continued

A detailed history reveals that the patient has had a chronic cough, which has been productive of mucopurulent sputum with occasional chest discomfort and episodes of hemoptysis during the past 2 months. The patient also reports low-grade fevers, malaise, generalized fatigue, and a 10-pound weight loss over a 1-month period. Although the patient has received several antibiotic regimens, which have included tetracyclines and macrolides, his symptoms and radiographic findings have not improved. Sputum Gram stain and cultures did not reveal any organisms.

Discussion

The patient’s history, physical findings, and radiographic changes are suggestive of a chronic pulmonary infection. Given the resistance to antibiotic therapy, the diagnosis of atypical pneumonias should be further investigated. The causative pathogens of atypical pneumonias may be bacterial, fungal, or viral. In general, viral pathogens do not cause lobar pathology or mass-like lesions in immunocompetent patients. Fungal infection, in addition to an atypical bacterial etiology, including tuberculosis, should be evaluated. The more common pathogens of the atypical bacterial pneumonias in immunocompetent patients are Mycoplasma pneumonia, Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydia pneumonia, oral anaerobes, Chlamydia psittaci, and Coxiella burnetii. The patient’s symptoms, radiographic findings, and travel history suggest a high likelihood of an endemic fungal infection such as histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, or coccidioidomycosis. Although the diagnosis of malignancy is highly unlikely in a 24-year-old, it should be excluded in any patient with a persistent mass or infiltrate that does not respond to antibiotic treatment.

Recommendation

Because the patient has consistent production of mucopurulent sputum, repeat sputum studies should be obtained. Stains and culture mediums for fungal, as well as mycobacterial, strains should be requested. Although the patient’s history is not suggestive of exposure to tuberculosis, a tuberculin skin test should be performed. A flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy with bronchial washings, bronchoalveolar lavage, and possible transbronchial biopsy should also be considered. Empiric treatment for fungus or tuberculosis is not indicated unless an organism is identified.

Discussion

Fungal infection of the lung is best established by staining or culture of the infecting organism. Occasionally, it is not possible to recover organisms in the stained specimens. The two stains most commonly used for demonstration of fungi are periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and methenamine silver stains. Other stains include a wet sputum preparation with immediate KOH staining and cytologic evaluation with Papanicolaou’s (PAP) smear. For optimal fungal cultures, all specimens should be inoculated on different types of culture media. Sabouraud’s dextrose agar is an excellent medium because it inhibits contaminating bacteria. Specimens should also be inoculated onto a second medium containing antibiotics and cycloheximide to suppress less fastidious bacteria and contaminating molds. Because this medium inhibits Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus, Sabouraud’s agar should be used in conjunction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree