Figure 4.1

(a, b) The patient is placed supine with a roll under the shoulders to extend the neck. The head is stabilized with a ring in axial alignment. If the trachea is not totally occluded, we prefer to start the operation with a laryngeal mask (LM), which permits adequate ventilation and avoids the need for tracheal instrumentation before the surgery. If the patient has a tracheostomy, it is replaced by a tube through the ostomy. If safe ventilation cannot be achieved with an LM, an orotracheal tube should be used; tracheal dilation may be needed under direct vision using a rigid bronchoscope. The sterile field is prepared to include the neck to the level of the mandible and the anterior chest covering the entire sternum. The choice of incision depends on the location of the stenosis. For most upper and mid-tracheal lesions, a cervical collar incision is appropriate and may be extended to a partial or complete sternotomy if necessary. Lower tracheal lesions are best approached through a sternotomy or right thoracotomy. A low cervical collar incision is made. Upper and lower skin flaps are dissected to the level of the thyroid cartilage and sternal notch, respectively, and laterally to the sternocleidomastoid muscle level. Dissection continues opening the midline, sparing the pretracheal muscles laterally to expose the ventral trachea. An Adson retractor is placed at this level. Usually, the thyroid isthmus must be ligated and divided for better exposure. If the tracheal lesion is at or close to a tracheostomy, the tracheostomy site is resected along with the skin incision. If the damaged trachea does not include the tracheostomy site, it is preferable to leave it alone and wait for spontaneous healing

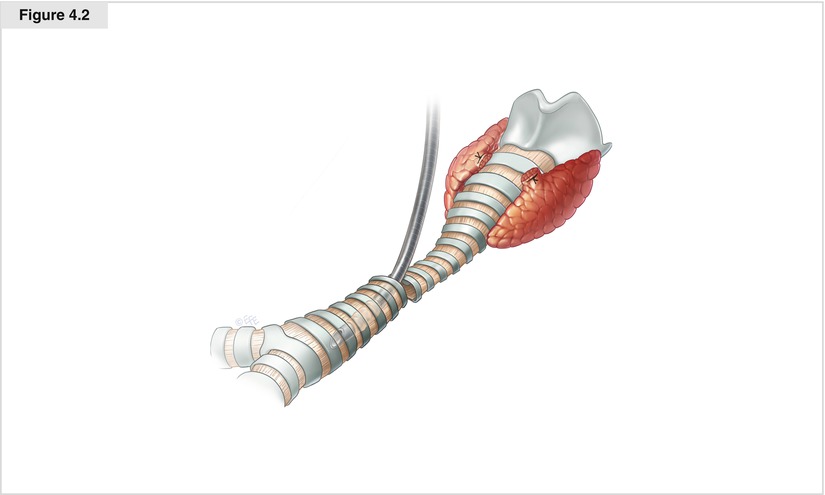

Figure 4.2

At this time, the stenosed tracheal segment must be identified. Sometimes, the external trachea looks almost normal, and the diseased segment must be identified under flexible bronchoscopic vision. Once recognized, the dissection progresses around the lateral and posterior trachea at this level. Staying close to the tracheal wall avoids injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerves and the esophagus in the lateral and posterior aspects of the trachea. Because the tracheal blood supply is located on the lateral aspects, the lateral dissection should be limited to the stenosed segment as much as possible. If posterior separation from the esophagus becomes difficult because of firm adhesions, the anterior trachea may be opened between cartilages at this level and the membranous trachea dissected free under direct vision. Before the trachea is opened, an armed endotracheal tube is passed to the anesthesiologist to create a sterile ventilation circuit into the operative field. The tracheal wall is partially opened at the inferior extent of the stenosis. Stay sutures are placed in healthy tissue, and the trachea is totally transected

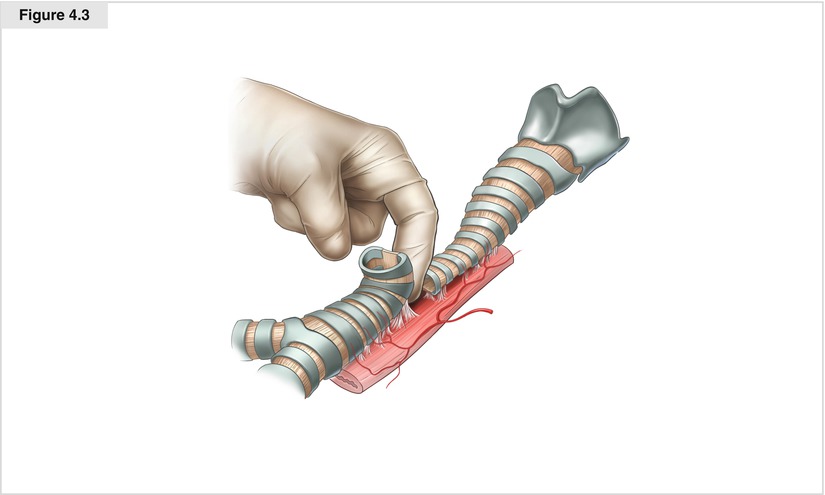

Figure 4.3

The anterior and posterior trachea is freed from the surrounding structures with blunt finger dissection to the carinal level, preserving the lateral vascular attachments. The plane of separation must be direct on the tracheal wall to avoid injury to the brachiocephalic artery and esophagus. Intermittent ventilation is reassumed by the armored tube. If an endotracheal tube was used to initiate the operation, it is useful to leave a heavy silk suture attached to the distal opening and to avoid removing the tube completely. During ventilation through the distal trachea, the posterior dissection of the upper trachea continues until the cricoid plate is located. The trachea is transected at the upper border of the stenosis, and the injured segment is removed. The tracheal resection must include all injured cartilage and inflamed mucosa, and it is important for the feasibility of reconstruction to have been confirmed preoperatively. It is better to start with a limited resection because it can always be extended if necessary. To assess how easily the trachea can be approximated without tension, the distal tracheal end is pulled up gently with the stay sutures while the anesthesiologist raises the head, flexing the chin over the chest. If there is excessive tension at the anastomosis, laryngeal release maneuvers may be necessary. Both the thyrohyoid (Dedo) and suprahyoid (Montgomery) maneuvers have been described to facilitate reconstruction of the upper and mid-trachea (Grillo 2003b). However, the author has never had to use any of these techniques, even with larger resections

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree