The operation is performed with the patient supine and the arm on the donor side abducted to 90 degrees, nearly always with general anesthesia. Towels, gel pads, intravenous fluid bags wrapped in towels, or other suitable padding is placed between the patient and the operating table on the side of the axillofemoral component to elevate the flank and lower chest. The patient is prepped from the neck to the lower anterior thighs including the intervening abdomen, ipsilateral flank, and chest including the sternum to allow entry to the abdomen and ipsilateral chest or a sternotomy (although none of these has ever been required in the author’s practice). Perioperative prophylactic antibiotics are administered and continued for 24 hours. Specific antibiotic coverage is administered as necessary in cases of an established remote infection when surgery cannot be delayed in an attempt to clear the infection.

The donor axillary artery is exposed using a transverse incision inferior to the middle of the ipsilateral clavicle, splitting of the pectoralis major muscle fibers, and division of the deep fascia. Exposure and control of the axillary artery is in most cases facilitated by ligation and division of at least one large crossing vein. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the adjacent axillosubclavian vein and brachial plexus elements. The axillary artery is less robust than the more familiar femoral artery and must be treated with great care to avoid injury. The author does not divide the pectoralis minor muscle as some have recommended. A critical technical point is to keep the graft anastomosis as medial as possible on the axillary artery to reduce the tendency for later arm abduction to disrupt the anastomosis. Leaving the pectoralis minor intact forces the surgeon to keep the anastomosis medial. One or both femoral arteries are exposed through standard groin incisions. A longitudinal groin incision is used most often because it allows more flexibility depending on findings at inspection of the target arteries.

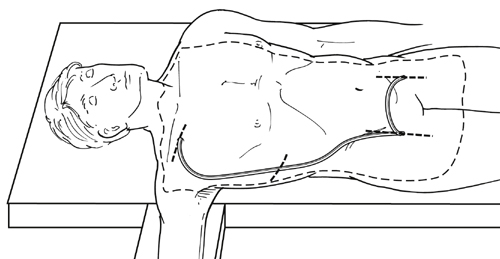

The axillofemoral graft is tunneled from the axillary artery exposure to the femoral exposure, which is nearly always ipsilateral (Figure 1). Circumstances requiring bypass from one axillary artery to a single contralateral femoral target are rare. The author’s team’s practice is to tunnel the graft posterior to the pectoralis minor muscle, but the graft may be tunneled anterior to the pectoralis minor, or the pectoralis minor may be divided, and there is no evidence that this affects outcome. The graft should be tunneled in the subcutaneous tissue in the midaxillary line to prevent kinking during subsequent patient torsoflexion and compression/angulation of the graft by the costal margin, which tends to be more prominent anteriorly. Classic descriptions of the operation have included an intermediate incision in the flank to facilitate tunneling, but we prefer to use a long enough tubular tunneler that allows tunneling without any intermediate incision.

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue

Related

![]()