28 Atrial Fibrillation

Definition and Classification

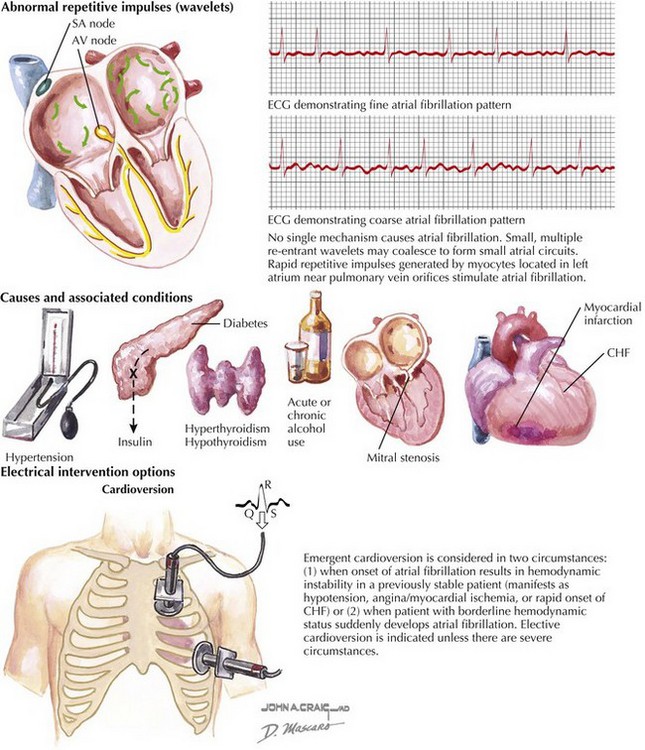

On ECG, AF is characterized by the replacement of P waves with rapid oscillating or fibrillatory waves that vary in amplitude, shape, and timing associated with an irregular ventricular response (Fig. 28-1). The rapidity of the ventricular response to AF depends on properties of the atrioventricular (AV) node, the level of autonomic tone, the presence of accessory conduction pathways, and the effects of various medications. AF may occur in association with other arrhythmias, including atrial flutter or atrial tachycardia.

Figure 28-1 Atrial fibrillation.

AV, atrioventricular; CHF, congestive heart failure; ECG, electrocardiogram; SA, sinoarterial.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

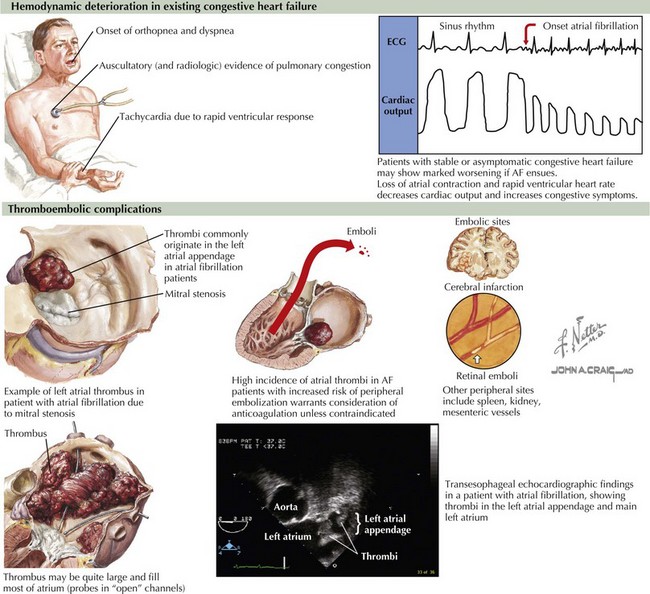

AF acutely has adverse hemodynamic consequences as a result of loss of synchronous atrial mechanical activity, irregularity of ventricular response, rapid heart rate, and impaired coronary arterial blood flow (Fig. 28-2). Loss of atrial contraction may most markedly affect cardiac output in those with impaired diastolic filling who are most dependent on atrial function, such as those with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) or hypertension.

AF is associated with a significantly increased risk of thromboembolic stroke (see Fig. 28-2). Reduced blood flow velocity in the left atrial appendage due to loss of organized mechanical contraction leads to stasis and thrombus formation. Thrombus formation generally requires continuation of AF for approximately 48 hours. However, even after cardioversion, atrial stunning (and minimally effective mechanical function of the atria) may be present for as long as 3 to 4 weeks, depending on the duration of AF.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Approach

AF may be related to multiple causes (Box 28-1), including acute causes such as binge alcohol intake, surgery, myocardial infarction, pericarditis, pulmonary disease, or hyperthyroidism (see Fig. 28-1). Most often, treatment of these conditions will lead to resolution of the AF. AF has been associated with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea. Multiple cardiovascular conditions are associated with AF, including valvular heart disease, heart failure, coronary artery disease, hypertension (particularly with LVH), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, and pericardial disease. In these conditions, treatment of the underlying cause does not usually abolish the AF. Familial AF has been increasingly recognized and is probably a result of genetic abnormalities leading to abnormal function of cardiac ion channels. Finally, approximately 30% to 45% of cases of paroxysmal AF and 20% to 25% of persistent AF occurs in patients without underlying predisposing conditions and is classified as lone AF.