chest pain

irregular heartbeat or palpitations

shortness of breath on exertion, lying down, or at night

cough

cyanosis or pallor

weakness

fatigue

unexplained weight change

swelling of the extremities

dizziness

headache

high or low blood pressure

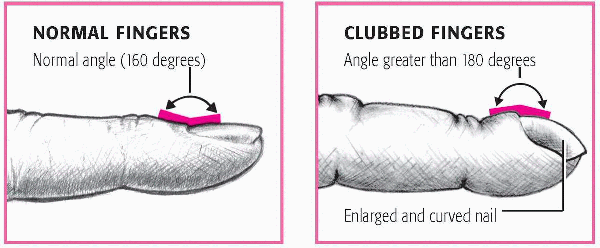

peripheral skin changes, such as decreased hair distribution, skin color changes, or a thin, shiny appearance to the skin

pain in the extremities, such as leg pain or cramps.

signs and symptoms. Ask about the location, radiation, intensity, and duration of any pain and any precipitating, exacerbating, or relieving factors. Ask him to rate the pain on a scale of 1 to 10, in which 1 means negligible and 10 means the worst pain imaginable.

AGE AWARE

AGE AWARE

Are you ever short of breath? If so, what activities cause you to be short of breath?

Do you feel dizzy or fatigued?

Do your rings or shoes feel tight?

Do your ankles swell?

Have you noticed changes in the color or sensation in your legs? If so, what are those changes?

If you have sores or ulcers, how quickly do they heal?

Do you stand or sit in one place for long periods at work?

How many pillows do you sleep on at night? (See Key questions for assessing cardiac function, page 26.)

congenital heart defects, and syncope. Other questions to ask include:

Are you still in pain? Where’s it located? Point to where you feel it.

Describe what the pain feels like. (If the patient needs prompting, ask if he feels a burning, tightness, or squeezing sensation in his chest.)

Does the pain radiate to any other part of your body? Your arm? Neck? Back? Jaw?

When did the pain begin? What relieves it? What makes it feel worse?

Tell me about any other feelings you’re experiencing. (If the patient needs prompting, suggest nausea, dizziness, or sweating.)

Tell me about any feelings of shortness of breath. Does a particular body position seem to bring this on? Which one? How long does the shortness of breath last? What relieves it?

Has sudden breathing trouble ever awakened you from sleep? Tell me more about this.

Do you ever wake up coughing? How often? Have you ever coughed up blood?

Does your heart ever pound or skip a beat? If so, when does this happen?

Do you ever get dizzy or faint? What seems to bring this on?

Tell me about any swelling in your ankles or feet. At what time of day? Does anything relieve the swelling?

Do you urinate more frequently at night?

Tell me how you feel while you’re doing your daily activities. Have you had to limit your activities or rest more often while doing them?

Have you ever had severe fatigue not caused by exertion?

Are you taking any prescription, over-the-counter, or illicit drugs?

Are you allergic to any drugs, foods, or other products? If yes, describe the reaction you experienced.

Have you begun menopause?

Do you use hormonal contraceptives or estrogen?

Have you experienced any medical problems during pregnancy? Have you ever had gestational hypertension?

MI, cardiomyopathy, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease (CAD), vascular disease, hyperlipidemia, or sudden death.

AGE AWARE

AGE AWARE

stress and how he deals with it

current health habits, such as smoking, alcohol intake, caffeine intake, exercise, and dietary intake of fat and sodium

environmental or occupational considerations

activities of daily living.

about exposing her chest, explain each assessment step beforehand, use drapes appropriately, and expose only the area being assessed. If the patient experiences cardiovascular difficulties, alter the order of the assessment as needed.

RED FLAG

RED FLAG

cardiovascular inflammation or infection

heightened cardiac workload (Assess a febrile patient with heart disease for signs of increased cardiac workload such as tachycardia.)

MI or acute pericarditis (mild to moderate fever usually occurs 2 to 5 days after an MI when the healing infarct passes through the inflammatory stage)

infections, such as infective endocarditis, which causes fever spikes (high fever).

RED FLAG

RED FLAG |

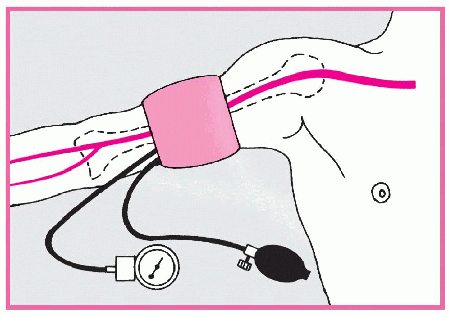

Wrong-sized cuff. Select the appropriate-sized cuff for the patient. This ensures that adequate pressure is applied to compress the brachial artery during cuff inflation. If the cuff bladder is too narrow, a false-high reading will be obtained; too wide, a false-low reading. The cuff bladder width should be about 40% of the circumference of the midpoint of the limb; bladder length should be twice the width. If the arm circumference is less than 13″ (33 cm), select a regularsized cuff; if it’s between 13″ and 16″ (33 to 40.5 cm), a large-sized cuff; if it’s more than 16″, a thigh cuff. Pediatric cuffs are also available.

Slow cuff deflation, causing venous congestion. Don’t deflate the cuff more slowly than 2 mm Hg/heartbeat; you’ll get a false-high reading.

Cuff wrapped too loosely, reducing its effective width. Tighten the cuff to avoid a false-high reading.

Mercury column not read at eye level. Read the mercury column at eye level. If the column is below eye level, you may record a false-low reading; if it’s above eye level, a false-high reading.

Poorly timed measurement. Don’t take the patient’s blood pressure if he appears anxious or has just eaten or been ambulating; you’ll get a false-high reading.

Incorrect position of the arm. Keep the patient’s arm level with his heart to avoid a false-low reading.

Failure to notice an auscultatory gap (sound fades out for 10 to 15 mm Hg then returns). To avoid missing the top Korotkoff sounds, stimulate systolic pressure by palpation first.

Inaudibility of feeble sounds. Before reinflating the cuff, have the patient raise his arm to reduce venous pressure and amplify low-volume sounds. After inflating the cuff, lower the patient’s arm; then deflate the cuff and listen. Or, with the patient’s arm positioned at heart level, inflate the cuff and have the patient make a fist. Have him rapidly open and close his hand 10 times before you begin to deflate the cuff; then listen. Be sure to document that the blood pressure reading was augmented.

increased stroke volume, which occurs with exercise, anxiety, and bradycardia

declined peripheral vascular resistance or aortic distention, which occurs with anemia, hyperthyroidism, fever, hypertension, aortic coarctation, and aging.

mitral or aortic stenosis, which occurs with mechanical obstruction

constricted peripheral vessels, which occurs with shock

declined stroke volume, which occurs with heart failure, hypovolemia, cardiac tamponade, or tachycardia.

tachypnea with low cardiac output

dyspnea, a possible indicator of heart failure (not evident at rest; however, pausing occurs after only a few words to take breaths)

Cheyne-Stokes respirations, possibly accompanying severe heart failure (seen especially with coma)

shallow breathing, possibly seen with acute pericarditis (deep respirations occur in an attempt to reduce the pain associated with deep respirations).

determine risk factors

calculate hemodynamic indexes (such as cardiac index)

guide treatment plans

determine medication dosages

assist with nutritional counseling

detect fluid overload.

RED FLAG

RED FLAG

central cyanosis, suggesting reduced oxygen intake or transport from the lungs to the bloodstream, which may occur with heart failure

peripheral cyanosis, suggesting constriction of peripheral arterioles, a natural response to cold or anxiety or a result of hypovolemia, cardiogenic shock, or a vasoconstrictive disease.

earlobes, and nail beds for signs of peripheral cyanosis. The color range for normal mucous membranes is narrower than that for the skin; therefore, it provides a more accurate assessment. In a darkskinned patient, inspect the oral mucous membranes, such as the lips and gingivae, which normally appear pink and moist but would appear ashen if cyanotic.

medications

excess heat

anxiety

fear.

Elevate one of the patient’s legs 12″ (30.5 cm) above heart level for 60 seconds.

Tell him to sit up and dangle both legs.

Compare the color of both legs.

dehydration, especially if the patient takes diuretics

age

malnutrition

adverse reaction to corticosteroid treatment.

aortic dissection

aortic valve incompetence

cardiomyopathy.

In a patient with a good arterial supply, color should return in less than 3 seconds.

|

that occur in xanthelasma result from lipid deposits and may signal severe hyperlipidemia, a risk factor of cardiovascular disease.

inspect

palpate

percuss

auscultate.

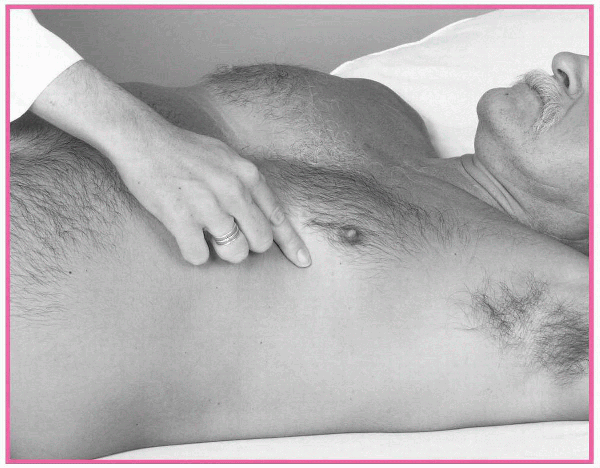

apical impulse. This is typically also the point of maximum impulse (PMI) and should be located in the fifth intercostal space medial to the left midclavicular line. The apical impulse gives an indication of how well the left ventricle is working because it corresponds to the apex of the heart. The impulse can be seen in about one-half of all adults.

AGE AWARE

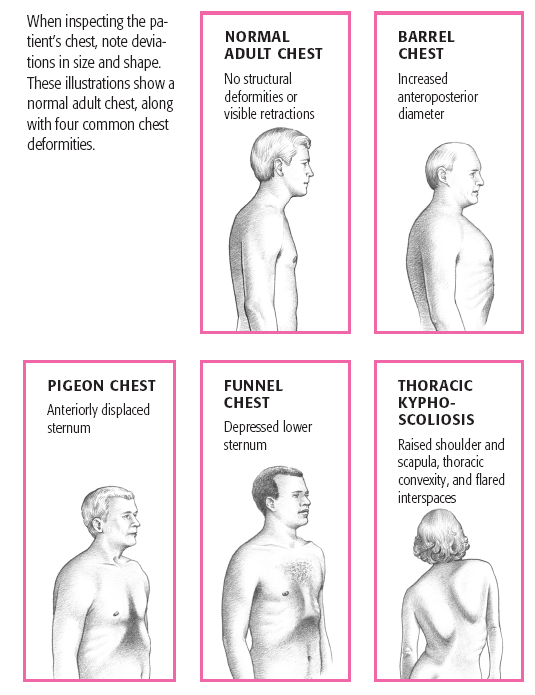

AGE AWAREexpansion and inhibiting heart muscle movement, whereas others can indicate cardiac disease:

barrel chest, indicated by a rounded thoracic cage caused by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

pectus excavatum, indicated by a depressed sternum

scoliosis, which is a lateral curvature of the spine

pectus carinatum, indicated by a protruding sternum

kyphosis, which is a convex curvature of the thoracic spine

retractions, indicated by visible indentations of the soft tissue covering the chest wall, or the use of accessory muscles to breathe, which typically results from a respiratory disorder, but may also indicate a congenital heart defect or heart failure

visible pulsation to the right of the sternum, a possible indication of aortic aneurysm

pulsation in the sternoclavicular or epigastric area, a possible indication of aortic aneurysm

sustained, forceful apical impulse, a possible indication of left ventricular hypertrophy, which increases blood pressure and may cause cardiomyopathy and mitral insufficiency

laterally displaced apical impulse, a possible sign of left ventricular hypertrophy.

apical impulse that exerts unusual force and lasts longer than one-third of the cardiac cycle—a possible indication of increased cardiac output

displaced or diffuse impulse—a possible indication of left ventricular hypertrophy

pulsation in the aortic, pulmonary, or right ventricular area—a sign of chamber enlargement or valvular disease

pulsation in the sternoclavicular or epigastric area—a sign of aortic aneurysm

palpable thrill or fine vibration—an indication of blood flow turbulence, usually related to valvular dysfunction (Determine how far the thrill radiates and make a mental note to listen for a murmur at this site during auscultation.)

heave or a strong outward thrust during systole along the left sternal border—an indication of right ventricular hypertrophy

heave over the left ventricular area—a sign of a ventricular aneurysm (A thin patient may experience a heave with exercise, fever, or anxiety because of increased cardiac output and more forceful contraction.)

displaced PMI—a possible indication of left ventricular hypertrophy caused by volume overload from mitral or aortic stenosis, septal defect, acute MI, or other disorder.

lying on his back with the head of the bed raised 30 to 45 degrees

sitting up

lying on his left side.

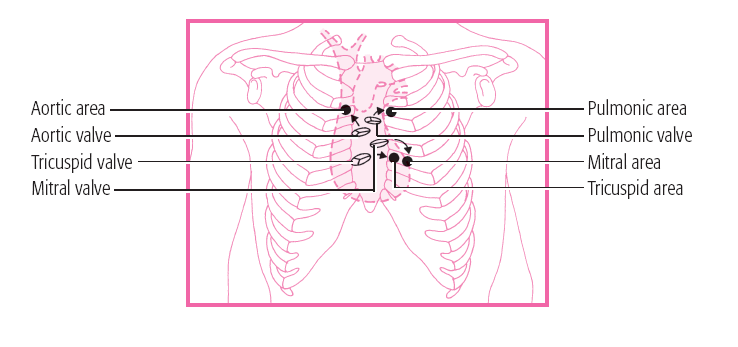

Place the stethoscope in the second intercostal space along the right sternal border, as shown. In the aortic area, blood moves from the left ventricle during systole, crossing the aortic valve and flowing through the aortic arch.

Move to the pulmonic area, located in the second intercostal space at the left sternal border. In the pulmonic area, blood ejected from the right ventricle during systole crosses the pulmonic valve and flows through the main pulmonary artery.

In the third auscultation site, assess the tricuspid area, which lies in the fifth intercostal space along the left sternal border. In the tricuspid area, sounds reflect blood movement from the right atrium across the tricuspid valve, filling the right ventricle during diastole.

Finally, listen in the mitral area, located in the fifth intercostal space near the midclavicular line. (If the patient’s heart is enlarged, the mitral area may be closer to the anterior axillary line.) In the mitral (apical) area, sounds represent blood flow across the mitral valve and left ventricular filling during diastole.

|

described as sounding like “lub.” It’s low-pitched and dull. S1 occurs at the beginning of ventricular systole. It may be split if the mitral valve closes just before the tricuspid.

SOUND | LOCATION | PITCH | TIMING | PATIENT POSITION | CAUSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

S3 | Apex | Low | Early to middiastole | Supine or left lateral | Noncompliant ventricle |

S4 | Mitral or tricuspid area (with bell of stethoscope) | Low | Late diastole | Supine | Atrial contraction into a noncompliant ventricle |

Summation gallop | Apex | Low | Middiastole | Left lateral | S3 and S4 occurring together to produce one heart sound |

Quadruple rhythm | Apex | Low | Throughout cardiac cycle | Left lateral | Hearing S1, S2, S3, and S4 |

Click | Apex or lower left sternal border | High | Mid to late systole | Sitting or standing | Tensing of the chordae tendineae and mitral valve cusps |

Snap | Apex along lower left sternal border | High | Mid to late diastole | Left lateral | Stenotic valve attempting to open |

Rub | Third left intercostal space at the lower left sternal border | High | Throughout systole, diastole, or both | Leaning forward | Pericarditis |

pressure changes

valvular dysfunctions

conduction defects.

AGE AWARE

AGE AWARE AGE AWARE

AGE AWARE

acute MI

hypertension

CAD

cardiomyopathy

angina

anemia

elevated left ventricular pressure

aortic stenosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree