54 Arrhythmias in Congenital Heart Disease

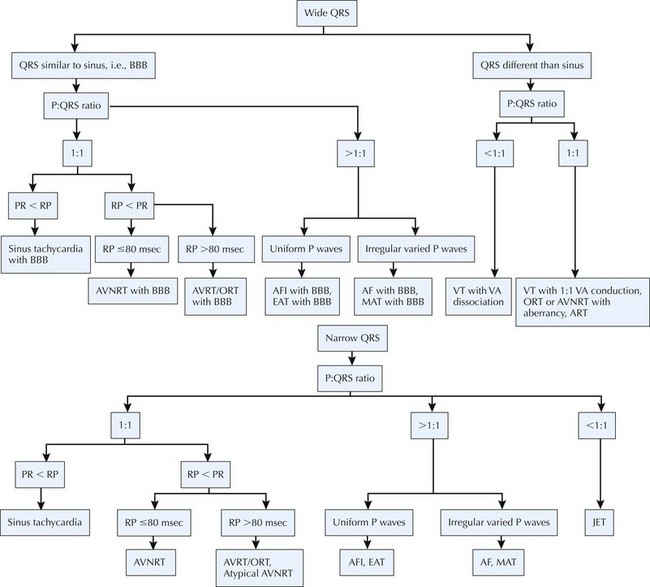

Advances in medical and surgical care of children with congenital heart disease have dramatically reduced mortality and, consequently, increased the population of children, adolescents, and adults with congenital heart disease. Arrhythmias are an important source of morbidity and mortality among these patients. Arrhythmias can result from congenital anomalies of the conducting system; from effects of chronic cyanosis, chamber distension, hypertrophy, and fibrosis; and from surgical intervention. Although the overall incidence of sudden death related to arrhythmias in congenital heart disease is low, subsets of patients are at considerable risk. Risk stratification continues to evolve, as do strategies for pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic arrhythmia management (Fig. 54-1).

Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease

Tetralogy of Fallot

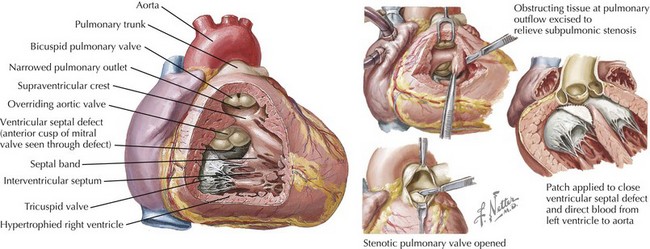

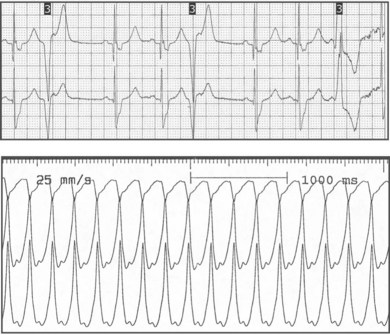

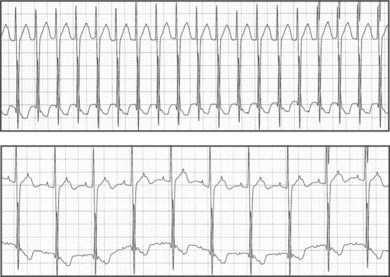

Electrocardiographic features of tetralogy typically are right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy and right-axis deviation. Among patients who have not undergone surgical repair, supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias are rare in childhood but can increase by adolescence (Fig. 54-2). After repair, right bundle branch block is present in most patients and left-axis deviation and PR interval prolongation are also occasionally seen. Although the long-term survival rate is excellent (nearly 90% at 30 years of age), ventricular arrhythmias are common. Significant ventricular arrhythmias are present in 5% to 10% of patients’ electrocardiograms (ECGs), in 20% to 40% of treadmill exercise recordings, and in 40% to 60% of ambulatory recordings (Fig. 54-3). The severity of ventricular arrhythmias increases with age at repair, RV pressure, and duration of follow-up. Electrophysiologic testing usually demonstrates a monomorphic macroreentry circuit involving the scarred RV outflow tract or the conal septum. The incidence of sudden cardiac death among long-term tetralogy survivors is 1.5% to 5%; however, the ability to identify those patients at highest risk is limited. Although some studies suggest that ambulatory recordings and/or invasive electrophysiology testing is useful, other reports are less compelling. One finding that is almost always useful is marked QRS prolongation. QRS duration of greater than 180 milliseconds indicates a risk of sustained ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. In addition to ventricular arrhythmias, supraventricular arrhythmias are common in long-term follow-up, with atrial flutter or fibrillation present in up to 25% of patients.

D-Transposition of the Great Arteries

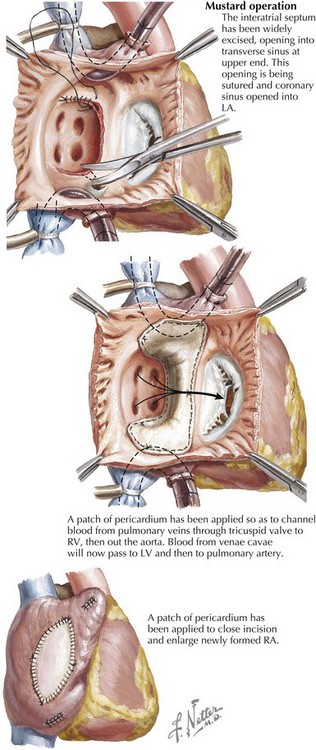

Electrocardiographic findings of unoperated D-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) primarily reflect the ventriculoarterial discordance of D-TGA (i.e., the right ventricle serving as the systemic ventricle), resulting in RV hypertrophy. Children with D-TGA require surgical repair. Atrial baffle (Mustard and Senning) procedures to direct pulmonary venous blood to the systemic (morphologic right) ventricle and systemic venous blood to the pulmonary (morphologic left) ventricle were for several decades the “repair of choice” for D-TGA (Fig. 54-4). Atrial baffle repair of D-TGA frequently produces direct trauma to the sinus node or its blood supply and creates conduction barriers by suture lines and scars—essentially substrates for atrial reentry rhythms. There is progressive loss of sinus rhythm: 5 to 10 years after atrial baffle surgery, only 20% to 40% of patients remain in sinus rhythm, 7% to 35% are in junctional rhythm, up to 40% are in slow ectopic atrial rhythm, and 10% have intra-atrial reentry. At longer follow-up, nearly half of these patients have supraventricular tachycardia, predominantly intra-atrial reentry. Loss of sinus rhythm and development of junctional rhythm are associated with an increased risk of development of symptomatic bradycardia. Ten years after atrial baffle surgery, approximately 8% of patients need cardiac pacing, which increases to approximately 20% of patients at 20 years’ follow-up. Sudden cardiac death occurs in 3% to 15% of patients after atrial baffle repair, with the risk seeming to be greater among patients with decreased right (systemic) ventricular function and among patients with uncontrolled intra-atrial reentry. Since the 1980s, most infants born with D-TGA have undergone the arterial switch procedure, resulting in a significant reduction of complex atrial arrhythmias. However, simple atrial ectopy is frequently seen, speculated to be related to balloon atrial septostomy, venous cannulation, or atrial defect repair.

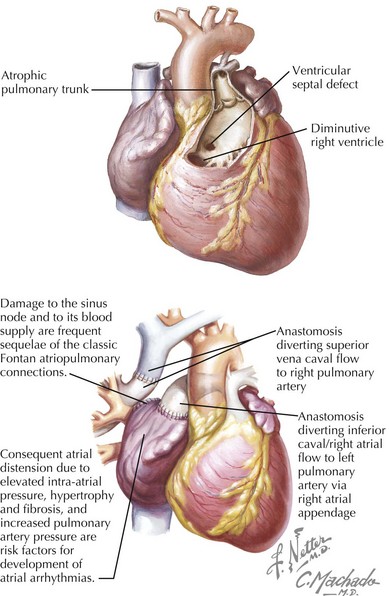

Tricuspid Atresia

Electrocardiographic findings of tricuspid atresia include right atrial (RA) enlargement, left-axis deviation, and increased left ventricular (LV) forces. A short PR interval is seen occasionally and is usually attributed to enhanced atrioventricular (AV) node conduction rather than to an accessory connection. Initially applied to tricuspid atresia and now increasingly to diverse single-ventricle variants, including hypoplastic left-sided heart syndrome, Fontan palliation (nearly always preceded by anastomosis of the superior vena cava to the pulmonary artery or hemi-Fontan staging) directs systemic venous blood to the pulmonary arteries (Fig. 54-5). In classic Fontan atriopulmonary connections, the sinus node or its blood supply is often interrupted and the atria are subjected to increased pressure, resulting in atrial distension, hypertrophy, and fibrosis. Surgical scars and patches produce conduction barriers that support intra-atrial reentry circuits, frequently involving the lateral atrial wall, the perimeter of the atrial septal defect (ASD) patch, and the inferomedial RA isthmus, the latter also being a component of typical atrial flutter in structurally normal hearts. The incidence of late atrial tachycardia after Fontan palliation is 30% to 50% at 5 years, and 5% to 15% of these patients require permanent pacemaker implantation. Advanced patient age at follow-up, increased RA size, and increased pulmonary artery pressure are risk factors for atrial arrhythmia development (Fig. 54-6). Late sudden cardiac death occurs in 2% to 3% of patients. Modification of surgical techniques to reduce atrial distension and atrial suture lines (e.g., lateral tunnel and extracardiac conduit modifications) has apparently reduced the incidence of atrial arrhythmias, although long-term follow-up is limited.

Ebstein’s Malformation

Electrocardiographic findings of Ebstein’s malformation typically include RA enlargement and RV conduction delay. Accessory connection–mediated supraventricular tachycardia is reported in 23% of patients. Most commonly supraventricular tachycardias in patients with Ebstein’s malformations are due to Wolff-Parkinson-White–type accessory pathways (Fig. 54-7). Concealed accessory connection–mediated tachycardia and AV node reentry tachycardia are less common. Catheter ablation techniques can be very useful in patients with Ebstein’s anomaly and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. However, multiple accessory connections can occur, and the altered tricuspid valve architecture results in higher procedural failure and recurrence rates compared with catheter ablation of accessory connections in structurally normal hearts. Surgical advances for improving tricuspid valve and right-sided heart function have dramatically reduced the development of late atrial reentrant tachycardia (Fig. 54-8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree