Ask specifically about previous cardiac disease, palpitations, blackouts, dizziness, chest pain, symptoms of heart failure, current medication.

|

Severe haemodynamic compromise (cardiac arrest, asystole, systolic blood pressure (SBP)<90 mmHg, severe pulmonary oedema, evidence of cerebral hypoperfusion) needs immediate treatment.

Give oxygen via face mask if the patient is hypoxic on air.

Keep nil by mouth (NBM) until definitive therapy has been started, to reduce the risk of aspiration in case of cardiac arrest or when the patient lies supine for temporary wire insertion.

Secure peripheral venous access.

Give atropine 1 mg IV (MiniJet®) bolus; repeat if necessary up to a maximum 3 mg.

Give isoprenaline 0.2 mg IV (MiniJet®) if there is a delay in pacing and the patient remains unstable. Set up an infusion (1 mg in 100 mL 1 M saline starting at 1 mL/min titrating to heart rate (HR)).

Insert temporary pacing wire (technique described in Temporary ventricular pacing, p. 808). If this is not possible immediately, set up an external pacing system and transfer to a screening room for transvenous pacing.

Temporary ventricular pacing, p. 808). If this is not possible immediately, set up an external pacing system and transfer to a screening room for transvenous pacing.

Look for and treat reversible causes; drug overdose (β-blockers, verapamil, diltiazem, digoxin), hypothyroidism, hypothermia, myocardial infarction (MI), infective endocarditis).

Ensure all possible underlying causes have been identified and removed.

Regardless of aetiology if symptomatic bradycardia remains refer for permanent pacing (see p. 530).

p. 530).

Complete heart block should always be referred for a permanent pacemaker, whether symptomatic or not.

In emergencies, external cardiac pacing (via an external defibrillator that can pace) may be used first, but this is only a temporary measure until a more ‘definitive’ transvenous pacing wire can be inserted.

The defibrillator ECG electrodes need to be attached.

Attach the defibrillation patches to the anterior and posterior chest wall. Turn the output up (in volts or amperes) until ventricular capture with QRS complexes is seen. This will also cause extremely unpleasant thoracic muscular capture, so the patient must be sedated with benzodiazepam

External cardiac pacing is useful as a standby in patients, e.g. post-MI, when the risks of prophylactic transvenous pacing after thrombolysis are high.

Haemodynamically stable patients with anterior MI and bifasicular block may be managed simply by application of the external pacing electrodes and having the pulse generator ready if necessary.

Familiarize yourself with the machine in your hospital when you have some time—a cardiac arrest is not the time to read the manual for the apparatus!

Young athletic individual

Healthy resting heart, e.g. sleep

Chronic degeneration of sinus or AV nodes or atria

Drugs—β-blockers, morphine, amiodarone, calcium-channel blockers, lithium, propafenone, clonidine

Increased vagal tone

vasovagal attack

nausea or vomiting

carotid sinus hypersensitivity

Hypothyroidism

Hypothermia

MI or ischaemia of the sinus node

Cholestatic jaundice

Raised intracranial pressure

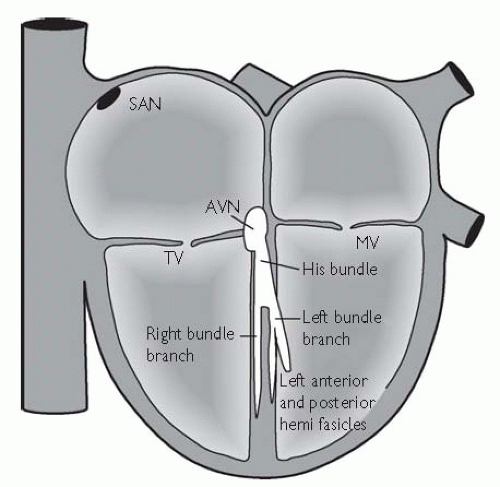

Mobitz 1 (Wenckebach): ECG shows the PR interval prolongs until a P wave is not conducted. The PR interval following the dropped P wave must be the shortest. The RR interval is therefore irregular. This block is characteristic of the AVN.

Mobitz 2: ECG shows a fixed P to QRS ratio of 2:1, 3:1, or 4:1. Block is predominantly at the His bundle and there is often an aberrant pattern to the QRS complex.

|

LBBB (Fig. 10.3): LV depolarization is delayed, giving a wide QRS, large notched R waves in leads I and V6, and a deep S wave (may be preceded by small R wave) in V1. Block confined to the anterior or posterior fascicles of the left bundle gives left-axis or right-axis deviation respectively on the ECG. BBB leads to asynchronous contraction of the left and right ventricle, which reduces cardiac output, important in heart failure.

RBBB: RV depolarization is delayed, giving wide QRS, an RSR pattern in V1, and a slurred S wave in I and V6. This can be a normal variant but more commonly as a result of causes listed above and, in addition, ASD, pulmonary embolism (PE), cor pulmonale.

Bifasicular block (Fig. 10.4) = RBBB + left anterior hemiblock (left-axis deviation on ECG), RBBB + left posterior hemiblock (right-axis deviation on ECG), or LBBB. All of these may progress to complete AV block.

Trifasicular block = bifasicular block + 1st-degree AV block.

Conventional teaching is that LBBB is always pathological, and thorough investigation for an underlying cause is needed (echocardiogram, cardiac MR, coronary angiography); however, a cause may not be found. RBBB may occur in otherwise completely normal hearts.

Hypertensive heart disease

Valve disease (especially aortic stenosis)

Conduction system fibrosis (aging)

Myocarditis or endocarditis

Cardiomyopathies

Pulmonary hypertension

Trauma or post-cardiac surgery

Neuromuscular disorders (myotonic dystrophy)

Polymyositis.

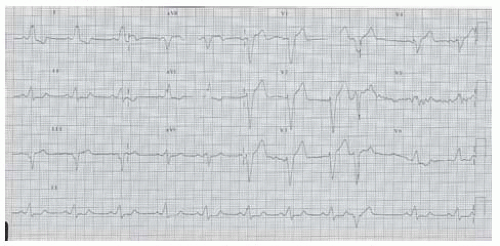

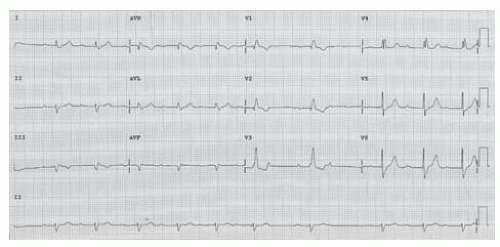

Fig. 10.4 ECG showing bifasicular block. There is a wide QRS complex with an rSr pattern in V1 and deep slurred S wave in V6 (=RBBB). The QRS in lead 1 is positive and lead aVF negative (=left anterior hemiblock). There is also 2nd-degree AV nodal block (Mobitz type 1 or Wenkebach). Observing the rhythm strip from the first P wave, there is a gradually prolonging PR interval and the P wave that follows the 6th QRS complex is blocked. |

Patients with cardiac arrest—immediate unsynchronized DC shock (follow advanced life support (ALS) guidelines)

Patients with signs of severe haemodynamic compromise:

shock; low BP, cool peripheries, sweating

cerebral hypoperfusion; confusion, agitated, depressed conscious level

pulmonary oedema

chest pain

Patients without haemodynamic compromise: record an ECG and diagnose tachyarrhythmia. Follow the treatment algorithm outlined here. If they deteriorate, treat as above.

tachy- (>120/min) vs. brady- (<60/min) arrhythmia

narrow (≤120 ms or 3 small squares) vs. broad QRS complex

regular vs. irregular rhythm.

The only exception is a patient in chronic AF with an uncontrolled ventricular rate—defibrillation is unlikely to cardiovert to sinus rhythm (SR). Rate control and treatment of precipitant is first-line.

Sedate awake patients with midazolam (2.5-10 mg IV) ± diamorphine (2.5-5 mg IV + metoclopramide 10 mg IV) for analgesia. Beware respiratory depression and have flumazenil and naloxone to hand.

Formal anaesthesia with propofol is preferred, but remember the patient may not have an empty stomach and precautions should be taken to prevent aspiration (e.g. cricoid pressure, endotracheal (ET) intubation).

Start at 200 J synchronized shock and increase as required.

If tachyarrhythmia recurs or is unresponsive try to correct ↓PaO2 (partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood), ↑PaCO2 (partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the arterial blood), acidosis or ↓K+. Give Mg2+ (8 mmol IV stat) and shock again. Amiodarone 150-300 mg bolus IV may also be used.

If there is ongoing ventricular tachycardia (VT) in the context of cardiac arrest or recurrent VT episodes, causing haemodynamic compromise, requiring repeated DC cardioversions then give IV amiodarone (300 mg IV bolus, followed by 1.2 g IV over 24 hours via central venous line). Follow Resuscitation Council periarrest arrhythmia guidelines.1

Try vagotonic manoeuvres (e.g. Valsalva/carotid sinus massage).

If diagnosis is clear, introduce appropriate treatment.

If there is doubt regarding diagnosis, give adenosine 6 mg as a fast IV bolus followed by 5 mL saline flush. If there is no response, try 9, 12, and 18 mg in succession with continuous ECG rhythm strip.

Definitive treatment should start as soon as diagnosis is known (see Treatment options in tachyarrhythmias, p. 721).

Treatment options in tachyarrhythmias, p. 721).

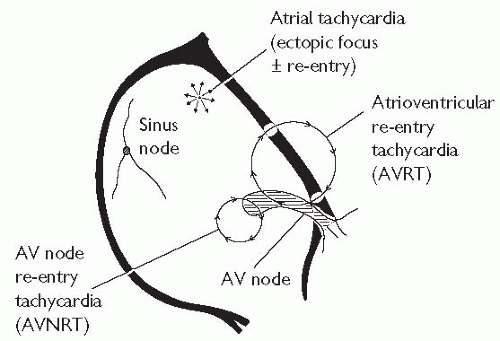

First episodes of atrioventricular node re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT), atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia (AVRT), or focal atrial tachycardia may need no further treatment. All other diagnoses and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW) should be referred to a cardiologist for further investigation and management.

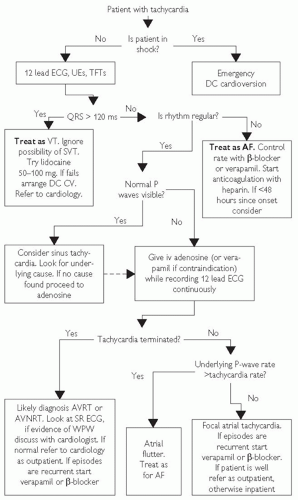

Fig. 10.5 Guidelines to the safe management of arrhythmias in the emergency department (adapted from Barts and the London NHS Trust A+E guidelines). CV = cardioversion; UEs = urea and electrolytes. |

junctional tachycardia.

independent P waves.

capture and fusion beats

QRS axis <-30 or >+90.

Concordance of QRS complexes in precordial leads (all positive or all negative)

Absence of RS or RS >100 ms in precordial leads

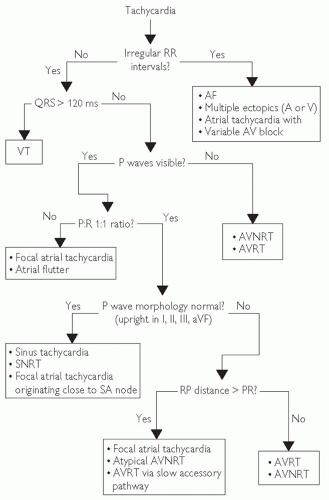

1:1 P:R, normal P-wave morphology: sinus tachycardia, focal atrial tachycardia originating from close to the SA node (high crista terminalis or right superior pulmonary vein) or, rarely, SNRT.

1:1 P:R, abnormal P-wave morphology: focal atrial tachycardia. AVRT or AVNRT (if slow activation from ventricle to atrium = long RP tachycardia).

P waves not visible: AVRT or AVNRT (with fast activation from ventricle to atrium). Compare QRS morphology in tachycardia with SR, as a slight deflection in the tachycardia QRS complex not seen in SR may represent the P wave,

P:R 2:1,3:1 or greater: focal or macro-re-entrant atrial tachycardia with AV nodal block.

P-wave rate >250/min: this defines atrial flutter (macro-re-entrant atrial tachycardia). Usually there will be 2:1 or 3:1 P:R ratio. In typical atrial flutter, a characteristic saw-tooth baseline is seen in the inferior leads.

Fig. 10.6 ECG diagnosis of tachycardia. |

|

Atrial arrhythmias: mechanism, p. 564). The circuit is not influenced by adenosine, and the AVN block reveals the underlying rhythm. It is usually (but not always) associated with structural heart disease. AFL exacerbates heart failure symptoms and, if incessant, will worsen LV function.

Atrial arrhythmias: mechanism, p. 564). The circuit is not influenced by adenosine, and the AVN block reveals the underlying rhythm. It is usually (but not always) associated with structural heart disease. AFL exacerbates heart failure symptoms and, if incessant, will worsen LV function.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree