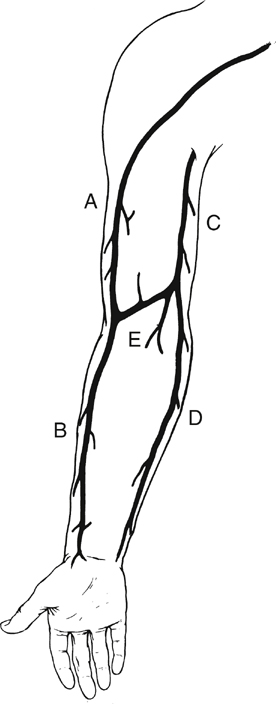

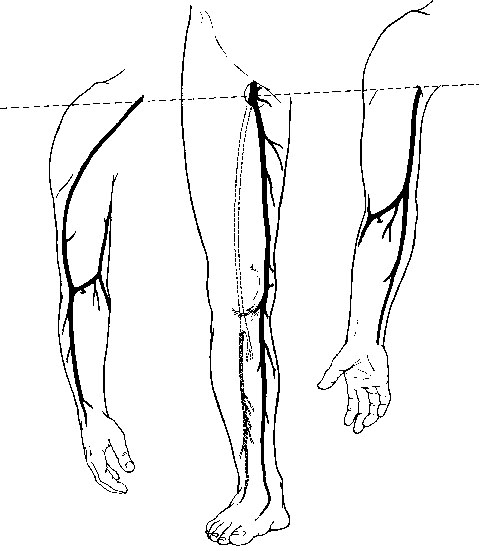

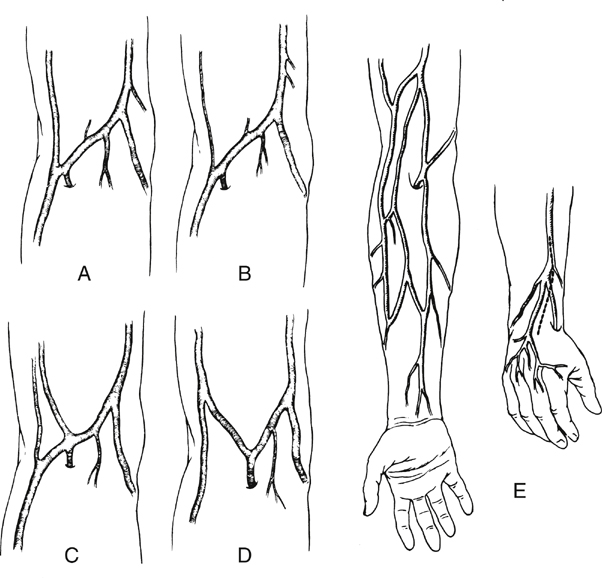

The cephalic vein arises at the anatomic snuff box of the wrist, courses on the lateral aspect of the arm and upper arm, continues in the deltopectoral groove, and ends in its confluence with the axillary vein. It is nearly uniform in diameter (5–7 mm) and is best used in the reversed configuration (Figure 1). The medially positioned basilic vein originates near the ulnar styloid process, passes anterior to the median condyle of the elbow, and widens as it terminates in the brachial or ultimately the axillary vein. At its largest end it measures 7 to 12 mm in diameter, tapering down to 3 to 5 mm (see Figure 1). The upper arm basilic vein normally joins one of the brachial veins near the axilla, although this juncture can occur anywhere along its course in the upper arm. One of the brachial veins can substitute for the basilic vein by arising as a direct continuation of the median antecubital vein. The median antecubital vein (MAV) interconnects the cephalic and basilic veins, is devoid of valves, and has numerous large, deep branches (see Figure 1). The entire basilic vein can span from the common femoral artery to the popliteal artery, whereas the cephalic vein is long enough to reach crural arteries in the midcalf (Figure 2). Two naturally occurring continuous grafts are also available in addition to the cephalic and basilic veins. The first consists of the forearm cephalic, median antecubital, and upper arm basilic segments (see Figure 1). We have used this graft reversed as well as nonreversed. When reversed, this graft usually tapers less than a reversed saphenous vein graft. A second continuous graft takes advantage of the segments with the largest diameters: the upper arm basilic, median antecubital, and upper arm cephalic veins (see Figure 1). The basilic vein is oriented at the proximal anastomosis because its diameter is opposite to the proximal artery. However, we have used this single-length segment successfully in less than half of the intended attempts. This low rate of use is the result of intimal damage and fibrous synechia within the median antecubital vein that often accompanies fibrosis of the adjacent forearm cephalic vein. Resection of the MAV and end-to-end anastomosis of the upper arm cephalic and basilic segments yields a graft that is 4 to 5 inches shorter. If a composite graft must be surgically constructed, the cephalic vein segment should be placed distally because of its smaller diameter. There are many anatomic variants of the arm veins, principally in the antecubital fossa and the forearm. The normal anatomy can vary, with one to four or more deep muscular branches occurring in the region of the cephalic–median antecubital juncture (Figure 3). A small upper arm cephalic vein is usually associated with an enlarged median antecubital vein connecting to the basilic vein (see Figure 3). Skin incisions must be placed precisely if there is duplication of the upper arm cephalic and forearm or wrist cephalic veins (see Figure 3). Convergence of the cephalic and basilic veins in the antecubital fossa to form a Y was thought to preclude the use of the aforementioned single-length upper arm loop grafts. This has not been a problem because the angles become unkinked under arterial pressure.

Arm Veins for Lower Extremity Arterial Reconstruction

Anatomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree