and Alessandra Cancellieri2

(1)

Department of Radiology, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy

(2)

Department of Pathology, Maggiore Hospital, Bologna, Italy

Clinical features | Micaela Romagnoli Rocco Trisolini | |

Pathology | Alessandra Cancellieri |

Classification of DLDs | DLDs associated to known causes Idiopathic DLDs IPAF | Page 2 Page 2 Page 3 |

Clinical evaluation | Acute, subacute, chronic History Key symptoms and signs | Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 |

Functional testing | Spirometry DLCO | Page 7 Page 8 |

Autoimmunity | Laboratory findings Systemic symptoms and signs | Page 9 Page 9 |

The most frequent clinical settings | IPF, NSIP, COP, sarcoidosis | Page 11 |

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) | Procedure and normal values Diagnostic role | Page 13 Page 13 |

TBNA, EBUS-TBNA EUS-FNA EUS-B-FNA | Procedures and diagnostic role | Page 18 |

Transbronchial biopsy (TBB) | Procedure Diagnostic role | Page 21 Page 21 |

Transbronchial cryobiopsy | Procedure Diagnostic role | Page 23 Page 23 |

Surgical lung biopsy in VATS | Procedure Diagnostic role | Page 25 Page 25 |

Multidisciplinary approach (MDA) | The role of MDA | Page 26 |

Classification of DLDs

Diffuse lung diseases (DLDs) are a heterogeneous group of lung disorders, consisting of inflammation and/or fibrosis of the pulmonary parenchyma, classified together because of some similar clinical, radiographic, physiologic or pathologic manifestations.

The differential diagnosis includes a broad range of diseases, and the treatment choices and prognosis significantly vary among the different causes and types of DLDs, so ascertaining the correct diagnosis is important.

DLD, interstitial lung disease (ILD) and diffuse parenchymal lung diseases (DPLD)

DLDs Associated to Known Causes

DLDs associated to known causes (~35 % of all patients with DLDs) are:

Connective tissue diseases (CTD)

Drug-induced lung diseases

Dust-associated pneumoconiosis

Familial pulmonary fibrosis

Hypersensitivity pneumonia (HP)

IgG4-related disease

Immunodeficiency (HIV, GVHD)

Idiopathic DLDs

Idiopathic DLDs (iDLDs) (~65 % of all patients with DLDs) may be classified according to the incidence in:

Major idiopathic interstitial pneumonias:

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

Idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP)

Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD)

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP)

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP)

Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP)

Rare idiopathic interstitial pneumonias:

Idiopathic lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP)

Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE)

Unclassifiable idiopathic interstitial pneumonias*

*Causes of unclassifiable ILDs include (a) insufficient clinical, radiologic or pathologic data and (b) discordance between clinical, radiologic and pathologic findings that may occur in patients previously treated or new pathologic entities/unusual variants of recognized entities.

Idiopathic DLDs

Idiopathic DLDs might also be classified according to clinical presentation:

Acute/subacute iDLDs:

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP)

Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP)

Chronic fibrosing iDLDs:

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

Idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP)

Smoking-related iDLDs:

Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD)

Travis WD (2013) An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188(6):733

American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society (2002) American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165:277

IPAF

Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) is a new entity in the DLDs context:

Many patients with an idiopathic DLD have clinical features suggesting an underlying autoimmune process, but do not meet established criteria for a definite CTD.

The ‘European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society Task Force on Undifferentiated Forms of Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Disease’ was formed to reach a consensus regarding the nomenclature and classification criteria for patients with DLD and features of autoimmunity.

The proposed term ‘interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features’ (IPAF) gives classification criteria mainly based on the combination of features from three domains: (1) clinical characteristics consisting of specific extra-thoracic features, (2) serologic characteristics consisting of specific autoantibodies and (3) morphologic characteristics based on specific chest imaging, histopathologic or functional features.

The term IPAF should be used to identify individuals with DLD and features suggestive of, but not definitive for, a CTD.

Fischer A (2015) An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society research statement: interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur Respir J 46(4):976

Cottin V (2016) Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias with connective tissue diseases features: a review. Respirology 21(2):245

Kim HC (2015) Interstitial pneumonia related to undifferentiated connective tissue disease: pathologic pattern and prognosis. Chest 147(1):165

Solomon JJ (2015) Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: a focused review. J Intensive Care Med 30(7):392

Epidemiology and Prognosis

Registries of epidemiology of different DLDs remain scarce, since these conditions are rare. Many of the available data come from prospective registries of data reported by respiratory physicians in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Spain and Greece. The data show that the most frequent DLDs are IPF and sarcoidosis, which together comprise about 50 %.

Prognosis significantly differs depending on DLD subtype. The 5-year survival rate is only about 20 % in IPF, about 60 % in LIP, 80 % in cellular NSIP, above 90 % in sarcoidosis and close to 100 % in COP. In general, DLDs that are associated with connective tissue diseases are recognized to have a better prognosis, although there are some conflicting data in literature on this issue.

The risk prediction is challenging in DLDs because of the heterogeneity in disease-specific and patient-specific variables.

The validated GAP model, a clinical prediction model based on sex, age and lung physiology, has been validated in patients with IPF and with DLDs other than IPF. The ILD-GAP model accurately predicts mortality in major chronic ILD subtypes and at all stages of disease.

Ley B (2012) A multidimensional index and staging system for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med 156(10):684

Ryerson CJ (2014) Predicting survival across chronic interstitial lung disease: the ILD-GAP model. Chest 145(4):723

The European Lung white book. Interstitial lung diseases 256, 2013 ERS

Clinical Evaluation

All successful diagnostic strategies begin with the patient. First of all it is an absolute requirement to know the tempo of the patient’s respiratory symptoms. Shortness of breath is the main clinical complaint when DLD is present, often accompanied by cough. Knowing whether these symptoms are acute (hours to several days), subacute (a few weeks to a few months) or chronic (many months to years) allows inclusion of some diseases and exclusion of others from the differential diagnosis. This knowledge also helps us to determine the nature of the critical pathology for this patient. Tables below present a view of the diseases most commonly associated with these three clinical presentations listed in alphabetical order.

Acute Diseases

The main acute (hours to several days) diseases are:

Acute exacerbation of chronic DLD

Acute injury related to drugs

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP)

Acute injury related to fumes and toxins

Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP)

ARDS

Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH)

Infection

Vasculitis

In the patient with acute clinical manifestations, further knowledge about his/her immunological status is very helpful, as suspicion for infection is always higher in immunocompromised hosts, and if bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and/or transbronchial biopsies are done, specimens always require additional studies to exclude an infectious organism (cultures and special stains for microorganisms).

Subacute Diseases

The main subacute (weeks to several months) diseases are:

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP)

Infection

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP)

Smoking-related disease

Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP)

Subacute injury related to CVD

Subacute injury related to drugs

Chronic Diseases

The main chronic (months to several years) diseases are:

Amyloidosis

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP)

Chronic injury related to CVD

Chronic injury related to drugs

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP)

Non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP)

Pneumoconioses

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP)

Sarcoidosis/berylliosis

Small airways disease

Smoking-related disease

Leslie KO (2009) My approach to interstitial lung disease using clinical, radiological and histopathological patterns. J Clin Pathol 62(5):387

Palmucci S (2014) Clinical and radiological features of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs): a pictorial review. Insights Imaging 5(3):347

History

In about one-third of patients with a DLD, the aetiology of the lung injury pattern is known, and it can be depicted by a detailed clinical history, taking into account all the possible known causes of lung injury (please see the above section ‘DLDs associated to known causes’).

A complete history should include information about:

Occupational and environmental exposure (asbestos, inorganic particles, organic dusts or animal antigens)

Smoking history

Drugs exposure

Pulmonary infection

Recent travel history

Immune disorders

Autoimmune disorders, e.g. connective tissue disease (CTD)

Family history (familial fibrosis)

When all these causes might be excluded, then the diagnosis will be of an idiopathic DLD.

Key Pulmonary Symptoms and Signs

Dyspnea (acute, subacute or chronic), mainly progressive exertional dyspnea

Dry cough

Chest pain

Hemoptysis

Wheezing

Inspiratory crackles at lower lobes (mainly in IPF, asbestosis, chronic HP)

Tachypnea (10–15 % of patients)

Inspiratory crackles, velcro sounds and rales

Dyspnea

Most of the patients with DLD present to the pulmonologist attention mainly because of chronic progressive dyspnea, which is mainly experienced during exertion, but it can also occur at rest at the end-stage disease, or it can present in an acute form during an exacerbation.

Differential diagnosis for acute dyspnea: pulmonary embolism, upper airway obstruction (foreign body aspiration, laryngospasm), acute asthma, pneumothorax, pneumonia, pulmonary oedema and cardiac ischaemia.

Differential diagnosis for chronic dyspnea includes asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cardiac failure.

Some patients with mild forms of DLDs, or at earlier stages, might be asymptomatic, and the radiologic or pulmonary function abnormalities can be discovered incidentally.

When in DLD the severity of dyspnea is worse than expected based on the extent of radiologic and functional abnormalities, one should consider the possibility of a complicating factor, e.g. pulmonary hypertension, or of a coexisting cardiac disorder.

Seeger W (2013) Pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol 62(25 Suppl):D109

Ryu JH (2007) Pulmonary hypertension in interstitial lung diseases. Mayo Clin Proc 82

Dry Cough

Dry cough is typically observed in patients with DLDs, and it may precede the onset of dyspnea.

Differential diagnosis for dry cough includes postnasal drip, gastroesophageal reflux disease, asthma and lung cancer.

Brown KK (2006) Chronic cough due to chronic interstitial pulmonary diseases: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 129(1 Suppl):180S

Chest Pain

Chest pain is related to a pleural disorder. In DLDs, chest pain might be present because of a pleuritis or a pleural effusion, e.g. in CTD-related DLDs, drug-induced DLDs, or because of a spontaneous pneumothorax, e.g. in LAM and LCH.

Hemoptysis

Coughing up of blood is not a frequent symptom in DLDs. However, it might be present in some specific DLDs, e.g. pulmonary vasculitis, CTD-DLDs, Goodpasture’s syndrome, drug-induced alveolar haemorrhage and idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis.

Wheezing

Wheezing is uncommon in patients with DLDs. However, some DLDs might be associated with airflow obstruction and wheezing, e.g. in sarcoidosis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (previously known as Churg-Strauss syndrome), respiratory bronchiolitis-associated ILD (RB-ILD), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Key Extrapulmonary Symptoms and Signs

Clubbing of the fingers and toes ( ). It is common in IPF but also in other chronic conditions: lung carcinoma, asbestosis, cystic fibrosis and arterio-venous malformation.

). It is common in IPF but also in other chronic conditions: lung carcinoma, asbestosis, cystic fibrosis and arterio-venous malformation.

Cutaneous neurofibromas ( ) are the hallmarks of Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis.

) are the hallmarks of Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis.

Erythema nodosum, uveitis, parotid enlargement and acute arthritis (sarcoidosis).

Fever.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) often present in scleroderma and IPF.

Haematuria (vasculitis).

Multiorgan involvement (connective tissue disease, vasculitis, amyloidosis, neurofibromatosis).

Neurologic symptoms (vasculitis, sarcoidosis, miliary TB).

Pulmonary hypertension.

Weight loss.

All the symptoms and signs, pulmonary and/or extrapulmonary, are not specific per se of DLDs, as they can be found in many other different respiratory diseases and heart dysfunction (lung cancer, emphysema, COPD, heart failure). Their presence together with the clinical context, chest X-ray and chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) findings makes the physician confident for the suspicion of a DLD, necessitating for further investigations.

Functional Testing

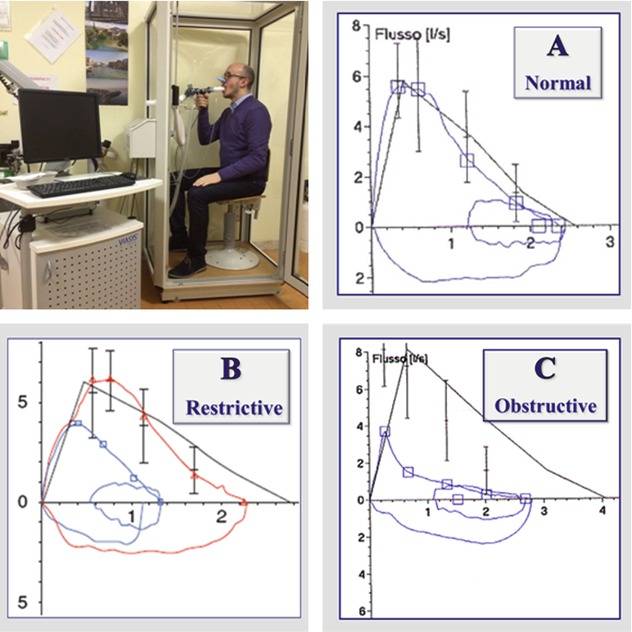

Spirometry

Normal: FVC, FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio are above the lower limit of normal. ATS recommendations: lower limit of normal is the result of the mean predicted value (based on the patient’s sex, age and height) minus 1.64 times the standard error of the estimate from the population study on which the reference equation is based. If the lower limit of normal is not available, the FVC and FEV1 should be greater than or equal to 80 % of predicted, and the FEV1/FVC ratio should be no more than 8–9 absolute percentage points below the predicted ratio.

Restrictive: FEV1/FVC ratio is normal, with relative preservation of the RV/TLC percentage, and reduced values of TLC, RV, FVC and FEV1.

Obstructive: FEV1/FVC ratio is reduced, with reduced FEV1, relative preservation of TLC and FVC and increased RV.

In DLDs spirometry might be normal, e.g. in the earlier stages of the disease, but most often it shows a typical restrictive pattern.

In some cases, severe obstructive defects, especially when they present acutely, e.g. during an asthma attack, can mimic a restrictive pattern, showing a normal FEV1/FVC ratio, and reduced values of both FVC and FEV1.

It is important in these cases to also measure TLC and RV, since contrarily to real restrictive trouble, TLC in these cases is normal or increased (and not reduced) and RV is increased (and not reduced).

Quanjer PH (1993) Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J 6(Suppl 16):S5

DLCO

The diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO, mL/min/mmHg) is usually decreased in DLDs. The decrease of DLCO is due in part to the thickening of the alveolo-capillary membrane, but also importantly to the mismatching of ventilation and perfusion of the alveolus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree