Approach to Claudication

James B. Froehlich

Sanjay Rajagopalan

Thomas W. Wakefield

PREVALENCE

Lower extremity atherosclerotic peripheral artery disease (PAD) is commonly encountered in clinical practice. Although prevalence figures vary widely, noninvasive testing (typically assessing the ankle-brachial index) indicates that prevalence increases sharply to rates in excess of 20% after 75 years. The vast majority of these are, however, asymptomatic; only 3% to 6% experience claudication at the age of 60 in most large population studies (1).

RISK FACTORS FOR CLAUDICATION

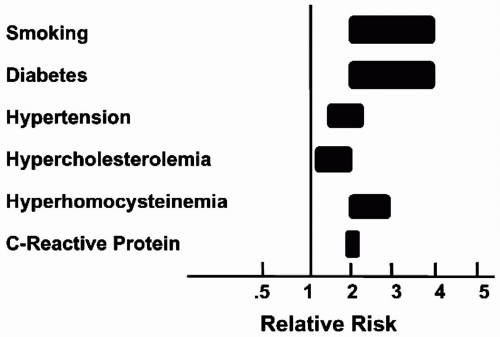

The risk factors for claudication are the same as those for atherosclerosis in general and are outlined in Fig. 6.1. Smoking and hyperhomocystinemia seem to have particularly strong associations with lower extremity atherosclerosis (1). In view of the commonality of risk factors and the systemic nature of atherosclerosis, it is not surprising that peripheral vascular disease is closely associated with coronary artery and cerebrovascular disease. Cardiac disease accounts for the majority of deaths in patients with peripheral vascular disease, in whom the relative risk of death from cardiac causes is increased more than fivefold (1).

PRESENTATION

Lower extremity occlusive disease is asymptomatic in the majority of patients, in whom it is commonly detected only by noninvasive screening. When it does manifest, lower extremity vascular occlusive disease typically causes intermittent claudication (derived from the Latin word for “limp”). Intermittent claudication is classically described as cramping pain or weakness that occurs with exercise and is relieved by rest, although atypical manifestations are well described (2). The pain is caused by inadequacy of the blood supply to contracting muscles and is therefore localized to muscle groups, including those of the buttocks, thigh, or, most commonly, the calf. The amount of exercise producing pain is usually reproducible, and patients can typically quantify their exercise capacity in terms of walking distance or time. Because endothelial function is an important determinant of symptoms, factors such as time of day, meals, and medications may influence symptoms. The pain of intermittent claudication is relieved, usually within 5 minutes, by rest and is sometimes relieved by slowing the pace of walking.

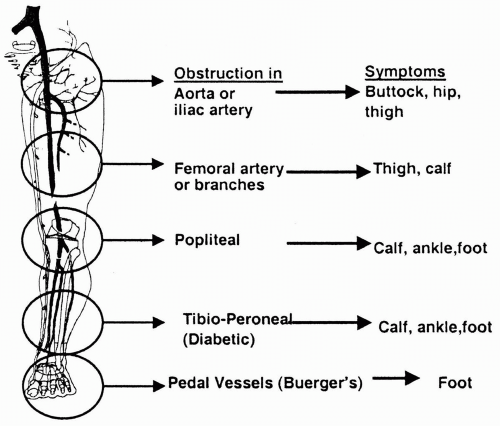

The examiner may deduce the level and extent of disease by considering the location and severity of discomfort. The amount of exercise required to precipitate pain is approximately inversely related to the severity of the narrowing of the vessel, and pain is usually manifested one segment below the area of stenosis. In other words, aortic disease is manifested by buttock pain; iliac disease, by thigh muscle pain; and superficial femoral arterial disease (in the most commonly affected artery), by calf claudication (Fig. 6.2). Because calf muscles may be more metabolically active than other muscle groups, calf symptoms often predominate in patients, irrespective of the level of

disease. Although exercise-induced calf discomfort is usually readily recognized as claudication, it is important to appreciate that aortoiliac disease may also produce aching discomfort in the hips and thighs along with a sensation of weakness in the lower extremity. As arterial insufficiency progresses, rest pain becomes a prominent feature as blood flow becomes insufficient to supply the basal needs of the sensory nerves. Rest pain is classically defined as severe nocturnal pain or a burning sensation that begins over the metatarsal heads or heels and is relieved by movement or dependency. Rest pain is a sign of very severe ischemia and suggests impending limb loss if no intervention is undertaken.

disease. Although exercise-induced calf discomfort is usually readily recognized as claudication, it is important to appreciate that aortoiliac disease may also produce aching discomfort in the hips and thighs along with a sensation of weakness in the lower extremity. As arterial insufficiency progresses, rest pain becomes a prominent feature as blood flow becomes insufficient to supply the basal needs of the sensory nerves. Rest pain is classically defined as severe nocturnal pain or a burning sensation that begins over the metatarsal heads or heels and is relieved by movement or dependency. Rest pain is a sign of very severe ischemia and suggests impending limb loss if no intervention is undertaken.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Vascular Causes

Apart from atherosclerotic involvement of the lower extremity vasculature, other vascular causes, such as peripheral embolization (heart or proximal vasculature, especially aneurysmal disease), coarctation of the aorta, and Buerger disease, must be considered.

Nonvascular Causes

Various nonvascular disorders mimic intermittent claudication. Of particular importance in the differential diagnosis are the following:

Neurogenic claudication (pseudoclaudication): This occurs secondary to impingement of the spinal cord by osteophytes or spinal stenosis. The pain characteristically occurs simply with assumption of the upright posture, although some patients think it is related to exertion. The pain is often described as an ache in the thighs, hips, and buttocks that may be associated with some numbness and is often relieved by stopping and changing posture (particularly by forward flexion of the lumbar spine or sitting). Patients with neurogenic claudication often find that whereas walking may produce symptoms, riding a bicycle (with forward flexion of the lumbar spine) will not cause the same symptoms at an equivalent amount of exertion. Likewise, walking up stairs is sometimes less painful than walking down, as the spine is usually held more upright walking downstairs, thus increasing spinal pressure.

Venous claudication: This condition, due to venous outflow obstruction, usually involving iliac veins, is often accompanied by signs of chronic venous insufficiency. Absence of such findings may help exclude the condition. Venous claudication is often described as a “bursting” discomfort in the limb with activity that is relieved with elevation of legs and with rest.

Compartment syndrome: This results from impaired venous outflow in the limb, usually secondary to hypertrophied muscles. This condition is most often described in athletes with significantly hypertrophied muscles, and a fairly high level of effort is characteristically necessary to induce the discomfort.

Neuropathic pain: Such pain follows the distribution of the dermatome and may be aggravated by exercise. It is often present at rest and can be relieved by changes in posture that relieve pressure on a peripheral nerve.

DIAGNOSIS

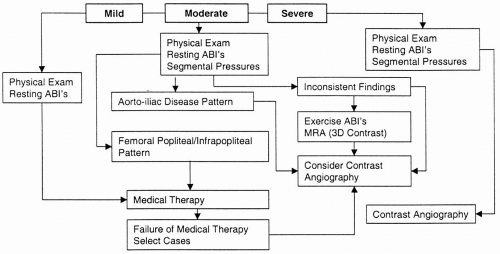

The approach should be individualized according to the severity of symptoms and the functional status of the patient. A strict algorithmic approach, as outlined in Fig. 6.3, although valuable in streamlining an approach to diagnosis, is seldom likely to be applicable in all patients. For instance, even moderately severe claudication could be an indication to proceed with contrast-enhanced angiography, especially if it involves an active individual whose lifestyle requires mobility. Severe symptoms in an elderly individual with a limited lifestyle may also prompt the physician to continue aggressive medical management. In general, the resting ankle/brachial index (ABI), segmental pressures, and Doppler

waveform analysis may be obtained in all patients with claudication. These measurements may help identify patients with predominantly aortoiliac disease who may benefit from early percutaneous intervention. This is in view of the excellent long-term patency rates of this procedure (more than 85% at 5 years) in selected patients with focal iliac artery disease. Patients with predominantly femoropopliteal or infrapopliteal disease who have moderate symptoms may be best managed medically, given the lower patency rates of percutaneous intervention in more distal vessels. In selected cases (failure of medical treatment or active lifestyle), contrast-enhanced angiography with the possibility of intervention (surgical/percutaneous) may be considered early on. For the patient with severe symptoms, and certainly for those with signs of rest pain, proceeding to contrast-enhanced angiography directly is justified to assess the suitability of the patient for surgical or percutaneous options.

waveform analysis may be obtained in all patients with claudication. These measurements may help identify patients with predominantly aortoiliac disease who may benefit from early percutaneous intervention. This is in view of the excellent long-term patency rates of this procedure (more than 85% at 5 years) in selected patients with focal iliac artery disease. Patients with predominantly femoropopliteal or infrapopliteal disease who have moderate symptoms may be best managed medically, given the lower patency rates of percutaneous intervention in more distal vessels. In selected cases (failure of medical treatment or active lifestyle), contrast-enhanced angiography with the possibility of intervention (surgical/percutaneous) may be considered early on. For the patient with severe symptoms, and certainly for those with signs of rest pain, proceeding to contrast-enhanced angiography directly is justified to assess the suitability of the patient for surgical or percutaneous options.

FIGURE 6.3. Diagnostic approach to a patient with claudication.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|