Apicoaortic Valved Conduit

Faisal G. Bakaeen

Denton A. Cooley

Introduction

Aortic valve bypass with a valved apicoaortic conduit is one of the options available to relieve left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction. The concept of creating a double-outlet left ventricle dates back to early work by Carrell in the early 1900s. Subsequently, largely experimental attempts to create such a conduit were fraught with limitations relating to hemorrhagic complications at the myocardial anastomosis and degeneration of the homograft valves. Refinements were introduced in the 1950s and 1970s, and better outcomes were achieved with the use of specialized prostheses. Dr. Cooley, the senior author of this chapter, and his colleagues built on their vast experimental work involving pumping prosthesis between the LV apex and the abdominal aorta and saw a clinical application of this technique through a modified nonpumping prosthetic LV apical–abdominal valved composite conduit.

Cooley et al. emphasized the necessity of rigid thromboresistant LVOT prostheses and described the use of alternative techniques with or without cardiopulmonary bypass. Their distal anastomosis was most commonly performed to the supraceliac abdominal aorta; other sites included the infrarenal aorta, ascending aorta, lesser curvature of the aortic arch, and descending aorta.

The apical-to–descending aortic conduit has gained traction in recent years through work by Brown and Gammie. In addition, cardiac surgeons have become more familiar with the ventricular apex because of the increased use of ventricular assist devices and the introduction of transapical transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) technologies. These trends have helped revive the use of the apicoaortic bypass option in select patients with LVOT obstruction.

Indications

Aortic valve bypass with an apicoaortic valved conduit is indicated for patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis or congenital forms of LVOT obstruction who are

not suitable candidates for traditional open surgery. Adult patients often have a porcelain ascending aorta or a hostile mediastinum. Conditions that create a hostile mediastinum include bypass grafts or cardiac structures that are adherent to the posterior table of the sternum and are at risk for injury during sternal re-entry, and dense mediastinal scarring from multiple previous operations or radiation.

not suitable candidates for traditional open surgery. Adult patients often have a porcelain ascending aorta or a hostile mediastinum. Conditions that create a hostile mediastinum include bypass grafts or cardiac structures that are adherent to the posterior table of the sternum and are at risk for injury during sternal re-entry, and dense mediastinal scarring from multiple previous operations or radiation.

Although TAVR is typically used as an alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in such high-risk patients, occasionally, TAVR is not possible because of unsuitable anatomic features of the aortic annulus or root, or because the transcatheter access options are poor.

Contraindications

Anatomically, a heavily diseased or porcelain descending thoracic or abdominal aorta precludes safe aortic clamping and anastomosis. Physiologically, significant aortic regurgitation is a contraindication for aortic valve bypass. In addition, a thoracotomy is best avoided in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Surgical access and exposure are compromised in morbidly obese patients. A thick layer of epicardial fat at the apex adds to the technical difficulty of the apical anastomosis. Also, dense adhesions in the chest or abdomen can complicate access to the aorta.

Steps taken in the work-up and preparation of the patient for apicoaortic conduits are similar to those taken in SAVR. Importantly, echocardiography is performed to confirm the LVOT obstruction and to rule out significant aortic regurgitation. Coronary angiography is performed to rule out hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease. Pulmonary function tests are particularly important in patients with a history of pulmonary disease to ensure that they can tolerate thoracotomy.

A computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast is important in defining the chest anatomy, identifying a suitable aortic anastomosis site, and determining whether femoral access is an option for cardiopulmonary bypass.

As noted earlier, there are a variety of approaches for apicoaortic conduit surgery, the choice of which is dictated by the site of the aortic anastomosis. For the purposes of this chapter, we will focus primarily on the procedure most commonly performed today, namely a left thoracotomy approach for an apical-to–descending aortic bypass.

Positioning and Access for Cardiopulmonary Bypass

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia and, preferably, with the use of a double-lumen endotracheal tube. A transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) probe is typically inserted in conjunction with routine monitoring lines. A Swan–Ganz catheter is useful, particularly in patients with depressed ejection fraction or pulmonary hypertension.

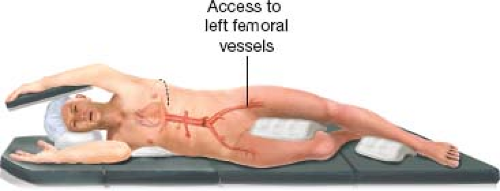

The patient is placed in a right lateral decubitus position with the shoulders at 90 degrees to the table and the hip at 45 degrees to give adequate access to the left femoral vessels (Fig. 5.1). If open access to the left femoral vessel is deemed necessary, the left femoral artery and vein are exposed through a horizontal skin incision just above the groin crease. A femoral arterial line is placed under direct vision, tunneled, and secured to the adjacent skin.

Arterial inflow for cardiopulmonary bypass is routinely performed through an 8-mm Dacron graft (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA). On a side table, this graft is sutured to the apicoaortic conduit, distal to the valve (see Conduit Assembly). If the need to

institute cardiopulmonary bypass arises before the conduit is anastomosed to the aorta, emergent inflow can be established via the left femoral artery with a 17F or 19F percutaneous cannula with initial wire access through the femoral arterial line.

institute cardiopulmonary bypass arises before the conduit is anastomosed to the aorta, emergent inflow can be established via the left femoral artery with a 17F or 19F percutaneous cannula with initial wire access through the femoral arterial line.

Venous outflow is achieved by a 19 to 23F percutaneous cannula advanced into the right atrium or superior vena cava under TEE guidance. Our preference is to place a 5-0 polypropylene purse string suture through which the venous cannula is deployed via a Seldinger approach. This allows easy closure of the vein at the time of decannulation.

Conduit Assembly

We currently use the commercially available Medtronic Hancock specialty product (Hancock, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN) (Fig. 5.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree