Surgery for Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Anthony L. Estrera

Kristofer M. Charlton-Ouw

Ali Azizzadeh

Hazim J. Safi

Indications

Aneurysms involving any part of the visceral aortic segment, from just above the celiac artery down to the lowest renal artery, are classified as thoracoabdominal. Most aneurysms are asymptomatic and the indication for repair is currently based on the maximal cross-sectional diameter. A thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) greater than 6 cm should be considered for elective repair. Fusiform aneurysms less than 5 cm can be observed with serial computed tomographic (CT) imaging. Aneurysms between 5 to 6 cm may be repaired or observed under an intensive CT surveillance protocol. The 5-year risk of rupture is greater than 30% for TAAAs greater than 6 cm in diameter. The mortality rate is estimated at over 90% in the first 24 hours after TAAA rupture, so elective repair before rupture is paramount.

TAAAs can be expected to increase in size by 1 to 3 mm per year. Patients with connective tissue disorders, symptoms, saccular aneurysms, and those with diameter increases of more than 5 mm in 6 months, are also at higher risk of rupture and are considered for earlier repair. Symptoms that may prompt early repair include chest, abdominal, or back pain. Expanding aneurysms can also compress adjacent structures, such as the lung, bronchus, esophagus, or the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, and may represent a less stable aortic state, necessitating urgent repair.

Although the exact mechanism of aneurysm formation is unknown, risk factors include increasing age, smoking, family history, and aortic dissection. There is no currently accepted pharmacologic therapy to limit aneurysm progression or prevent rupture. For patients with aortic dissection, systolic blood pressure target should be less than 120 mm Hg with a heart rate of less than 60 bpm. Patients with aortic dissection or aneurysm should be enrolled in a lifelong surveillance protocol.

Contraindications

The major contraindication for elective open TAAA repair is poor control of patient comorbidities such as infection, coronary artery, pulmonary and renal disease. We found that patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 67 mL/min/1.73 m2 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were at risk for postoperative complications. Age greater than 75 years was also a risk. The extent of aneurysm repair also predicts postoperative renal insufficiency. Aneurysms involving the renal arteries (extents II, III, and IV) were at highest risk for postoperative renal failure. Thus, several factors need to be weighed to determine whether patients are appropriate candidates for TAAA repair. In general, these same risks also apply when considering endovascular TAAA repair. Finally, patients with a life expectancy of less than 2 years should normally not be considered for elective repair. Consideration of repair in these settings may be considered in patients with severe symptoms and rupture after extensive education and discussion with the patient and family.

Preoperative evaluation of patients for elective TAAA repair should include a thorough history and physical examination and determination of the presence of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and renal diseases. Pulmonary function testing is obtained in patients with a history of smoking or pulmonary disease. There is controversy regarding optimal preoperative cardiac workup for noncardiac vascular disease, despite published practice guidelines. We found that preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction was the strongest cardiac predictor of mortality and we obtain echocardiography in all patients to assist in stratifying risk and to determine the need for additional cardiac testing. In addition, we will assess functional capacity using metabolic equivalents (1 MET = 3.5 mL of O2 uptake/kg/min) and determine if further evaluation is required. Treatment of coronary artery disease can be treated with medical therapy, coronary artery angioplasty, or coronary artery bypass prior to thoracoabdominal repair. The type of revascularization will depend on the degree of disease, taking into consideration the antiplatelet agents required after percutaneous interventions. It is unclear if preoperative coronary artery or carotid artery revascularization is beneficial in asymptomatic patients.

Renal function should be evaluated with estimation of GFR. Normal values are greater than 90 mL/min/1.73 m2. GFR is easy to estimate by several methods (e.g., Cockcroft–Gault, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease, or Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formulas) and is a better predictor of risk than serum creatinine. Several formulas are available on smartphones and can be calculated in seconds.

Axial imaging of the entire chest, abdomen, and pelvis is mandatory to determine extent of aneurysm as well as synchronous aneurysms. Intravenous CT contrast is useful, but is contraindicated in patients with impaired renal function (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). Newer magnetic resonance imaging sequences do not require contrast and are an acceptable alternative in patients with preoperative renal insufficiency.

Classification

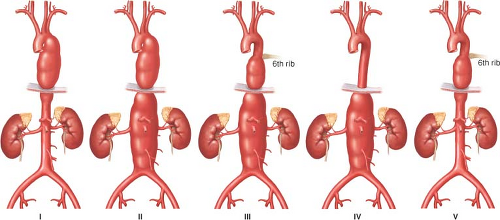

In an effort to associate the complications related to aneurysms, specifically paraplegia and paraparesis, aneurysms have been classified as follows (Fig. 15.1): Extent I is from the left subclavian artery to just below the renal artery; extent II is from the left subclavian to below the renal artery; extent III is from the 6th intercostal space to below the renal artery; extent IV is from the 12th intercostal space to the iliac bifurcation (i.e., total abdominal). In 1995, we added extent V, which is from the 6th intercostal space to above the renal arteries. Classifications are correlated with prognosis, especially the risk of spinal cord ischemia when not using surgical adjuncts, such as distal aortic perfusion.

Surgery

Our technique for descending aortic aneurysm and TAAA repair has evolved over the past two decades. The overall approach has been simplified so that a general approach can be applied to all types, whether descending or thoracoabdominal aneurysms.

Anesthesia

The patient is brought to the operating room and placed in the supine position on the operating table and prepared for surgery. The right radial artery is cannulated for continuous arterial pressure monitoring. General anesthesia is induced. Endotracheal intubation is established using a double lumen tube for selective one-lung ventilation during surgery. A sheath is inserted in the internal jugular vein, and a pulmonary balloon-tipped catheter is floated into the pulmonary artery for continuous monitoring of the central venous and pulmonary artery pressures. Large-bore central and peripheral venous lines are established for fluid and blood replacement therapy. Temperature probes are placed in the patient’s nasopharynx and bladder. Electrodes are attached to the scalp for electroencephalography and along the spinal cord for both motor- and somatosensory-evoked potential to assess the central nervous system and spinal cord function, respectively. The patient is then positioned on the right side with the hips and knees flexed to open the intervertebral spaces. A lumbar catheter is placed in the third or fourth lumbar space to provide cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure monitoring and drainage. The CSF pressure is kept at 10 mm Hg or less by gravity drainage of CSF fluid throughout the procedure.

Positioning

The position of the patient is of paramount importance. The patient should be positioned on the operative table with the shoulder blades at a right angle to the edge of the table, and the hips are tilted 60 degrees so that both femoral arteries are accessible. Good exposure of the chest and abdomen is also required.

Technique

Currently, the incision used is from the tip of the scapula to the costal cartilage along the sixth rib. This modified thoracoabdominal incision can be applied to all descending thoracic aortic aneurysm (DTAA) and TAAA extents I and V. The typical TAAA incision will begin as the modified version, from the tip of the scapula, and extending to the umbilicus if needed. This will be applied to TAAA extents II, III, and IV. We do not use the midline incision curve into the chest as it can lead to catastrophic necrosis of the upper portion of the abdominal incision.

Retroperitoneal Exposure

After entering the abdomen, we mobilize the left kidney and the viscera medially, exposing the aorta from the aortic hiatus to the iliac bifurcation. We prefer the retroperitoneal approach rather than the transperitoneal approach. The advantage of the retroperitoneal approach is to prevent the viscera, and especially the small bowel, from coming into the operative field, making closure easier. In addition, it decreases water and heat loss. The diaphragm is incised anteriorly in a circumferential fashion just to the point that allows adequate exposure of the aorta. A rim, left of the diaphragm, is left for easier closure. The crus of the diaphragm is also enlarged so as to be able to pass the prosthetic graft into the abdomen from the chest.

Distal Aortic Perfusion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree