Aortoiliac Occlusive Disease (Open Surgery)

JOHN P. DAVIS and GILBERT R. UPCHURCH Jr

Presentation

A 41-year-old gentleman presents to the clinic with a 24-month history of worsening pain in his buttocks and thighs that is exacerbated by walking or exertion. His pain is worse on the right when compared to the left, and it improves upon resting. The pain is not evident during rest or at night. He has a 26-pack-year smoking history and a past medical history of hyperlipidemia, for which he takes a statin. His surgical and family history are unremarkable. A diminished femoral pulse on the left and an absent femoral pulse on the right are noted on physical examination. Distal pulses are not palpable, but monophasic Doppler signals are evident bilaterally.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of buttock and thigh pain that is exacerbated with exercise is broad. The source of this pain could be neurogenic (spinal stenosis, lumbar disc rupture or bulge, or diabetic neuropathy), musculoskeletal (osteoarthritis of the hip or soft tissue injury), or vascular (arterial insufficiency).

Vascular insufficiency is the most likely origin given the nature of his symptoms and his physical examination findings. More specifically, this patient is likely suffering from aortoiliac disease given his buttock and thigh pain that is easily reproduced and occurs with increasing exertion. Additionally, bilateral diminished femoral pulses are consistent with aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD). When there is concern for arterial insufficiency, the examiner must focus on palpation of femoral, popliteal, and distal pulses. Femoral bruits, lower extremity pallor on elevation, hair loss, and thickened toenails are also signs that are indicative of lower extremity arterial insufficiency. Doppler examination is helpful in instances when pulses are abnormal.

Workup

Initial testing includes ankle-brachial indices (ABIs) and pulse volume recordings (PVRs). Additional imaging will be necessary if there are abnormalities in the initial testing.

Ankle-Brachial Indices and Pulse Volume Recordings

ABIs are helpful for determining the degree of arterial insufficiency. An ABI of 0.95 to 1.2 is considered normal, while an ABI of 0.5 to 0.95 is associated with claudication. An ABI of 0.2 to 0.5 is associated with rest pain. An ABI of 0 to 0.3 usually is associated with tissue loss or gangrene. ABIs greater than 1.3 are considered unreliable, as they are usually a result of calcified noncompressible vessels, which can be seen in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Some patients will give clinical histories and have examinations that support arterial insufficiency, but have normal resting ABIs. These patients benefit from ABI measurements after exercising. A 15% decrease in ABIs after exercising supports the diagnosis of arterial insufficiency.

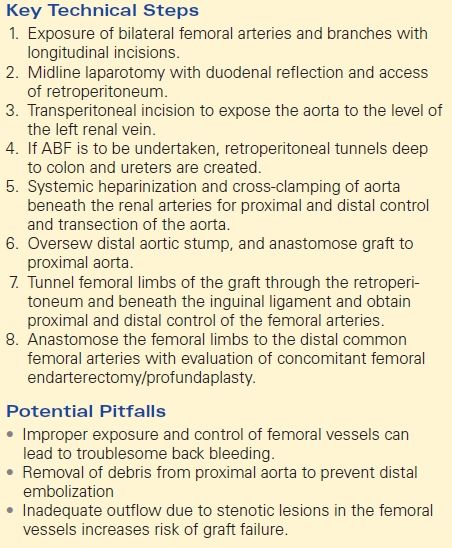

PVRs indirectly measure the pulsatility of a vessel. These tracings are particularly helpful when evaluating a patient with noncompressible vessels and falsely elevated ABIs. An elevated ABI and attenuated tracings on PVR suggest poor blood flow despite the elevated ABI. Patients with AIOD will have attenuated PVRs throughout the lower extremities (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1 PVR tracings from a patient with AIOD. Note the dampened waveforms in all tracings.

Cross-Sectional Imaging

CT Angiography (CTA) is the preferred imaging modality for preoperative evaluation as it allows for visualization of the aorta and the inflow vessels, outflow vessels, and runoff to the lower extremities. This is normally well tolerated in patients with normal renal function. Patients with borderline renal insufficiency are commonly hydrated prior to administration of the intravenous (IV) contrast. Sodium bicarbonate can be administered intravenously for further renal protection, though its efficacy may be in question.

Magnetic resonance angiography with gadolinium administration is an acceptable means of imaging in patients with renal insufficiency. It is usually well tolerated, but patients with renal insufficiency carry an increased risk of gadolinium-induced nephrogenic systemic sclerosis. Cross-sectional imaging gives the surgeon the ability to classify the severity of the disease.

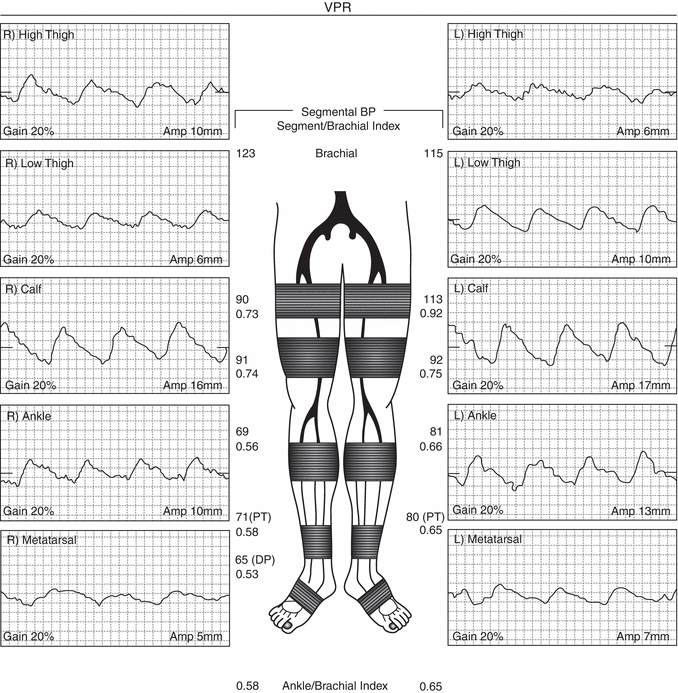

The most commonly utilized classification system is the Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASCII) classification (Fig. 2). Classification schemes range from type A to type D lesions, with type A lesions being more isolated and shorter, while type D lesions are more severe and longer. Recently, endovascular therapy is preferred for type A, B, and C lesions, while open surgery is reserved for type D lesions.

FIGURE 2 TASC II aortoiliac lesions (Adapted from Bekken JA, Vos JA, Aarts RA, et al. DISCOVER: Dutch Iliac Stent trial: COVERed balloon-expandable versus uncovered balloon-expandable stents in the common iliac artery: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:215).

Return to Scenario

The patient was referred to the vascular laboratory and underwent ABIs and PVRs. His ABIs were 0.58 on the right and 0.65 on the left. PVRs were obtained, which revealed moderately attenuated waveforms throughout the lower extremities indicative of inflow disease. CTA revealed an approximately 70% stenosis of the aorta secondary to mural thrombus that extended to the renal arteries (Fig. 3A). The renal arteries were patent bilaterally. Additionally, there was segmental occlusion of the right common iliac artery with severe stenosis of the left common iliac artery secondary to atherosclerotic plaque (Fig. 3B). This patient’s imaging was consistent with TASC D classification of disease.

FIGURE 3 A: CT imaging revealing a large mural thrombus extending to the level of the renal arteries. B: A 3D reconstruction revealing stenosis of the left common iliac artery and complete occlusion of the right common iliac artery.

Treatment Options

Medical Therapy

Initiation of risk factor modification and medical therapy is essential in patients with peripheral vascular disease and lower extremity arterial insufficiency. Smoking cessation strategies are essential in this patient population. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin or clopidogrel is beneficial in patients to reduce the risk of subsequent myocardial infarction and cerebroembolic events. Additionally, statin therapy, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and cilostazol have been shown to increase claudication-free walking times at 6 months. Most importantly, a walking regimen for patients with arterial insufficiency promotes collateralization and improves claudication without operative intervention. Medical therapy may be reserved in patients with less severe TASC A or B lesions, while intervention should be considered in patients with advanced lesions resulting in persistent or worsening claudication, rest pain, and/or tissue loss.

Surgical Approach

This patient is a young and otherwise healthy man with significant AIOD with severe lifestyle-limiting claudication. CTA revealed TASC D AIOD with mural thrombus that extended to the renal arteries. Endovascular therapy is considered in all patients with AIOD, but the nature of his disease, particularly the mural thrombus extending to the renal arteries, makes endovascular therapy less attractive. Therefore, this patient would benefit from open aortoiliac reconstruction. In addition to optimization of risk factors and medical therapy, patients with peripheral vascular disease must undergo stringent cardiac risk stratification and screening as patients with peripheral vascular disease have increased rates of concomitant coronary artery disease.

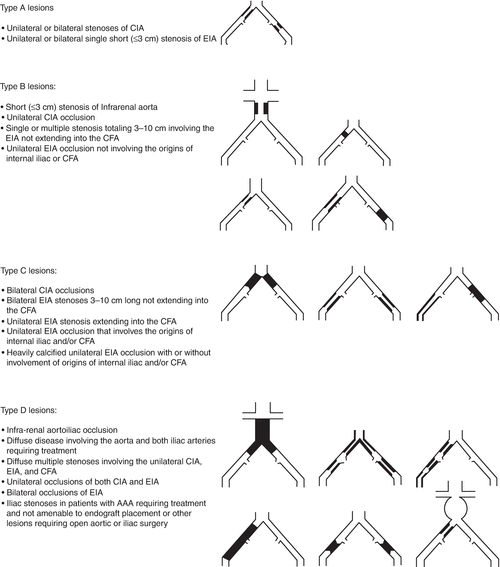

Aortobifemoral or aortobiiliac bypass is considered the gold standard for open reconstruction of the distal aorta and iliac vessels for AIOD, particularly in patients with advanced lesions (i.e., total aortic occlusion with extensive disease extending proximally to the renal arteries), worsening claudication, rest pain, or tissue loss. Table 1 describes key technical steps and common pitfalls.

TABLE 1. Aortiliac Occlusive Disease (Open Surgery)