Aortic Stenosis

Ragavendra R. Baliga

Mauro Moscucci

Michael J. Shea

G. Michael Deeb

DEFINITION

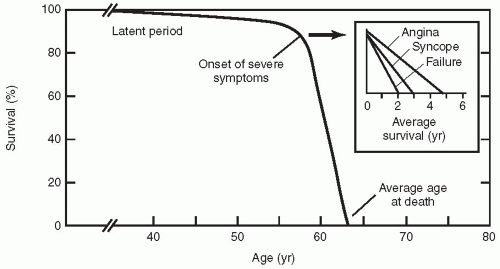

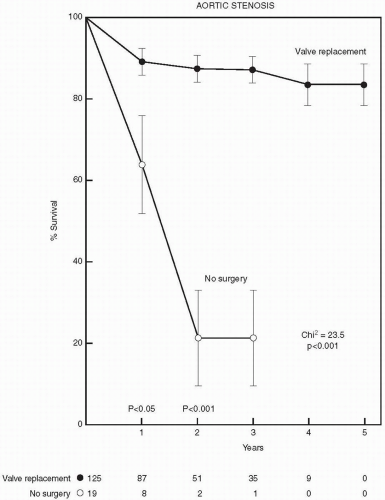

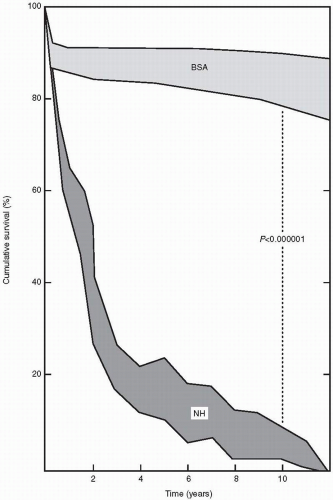

Valvular aortic stenosis is the most common valve lesion in adults in industrialized nations, and calcified aortic stenosis is the valve lesion most commonly considered for valve replacement in the United States, particularly in the elderly. The normal aortic valve has three leaflets and has an area of 2 to 3 cm2. Aortic stenosis is often not apparent until the valve orifice area is reduced by 50%. In general, patients are asymptomatic until the valve area is less than 1 cm2. The onset of symptoms is associated with a 2-year survival rate of less than 50% (Fig. 24.1). In contrast, adults with asymptomatic aortic stenosis have an excellent clinical prognosis.

USUAL CAUSES

Aortic stenosis is usually acquired and occurs in previously normal valves (Table 24.1). Seventy percent of affected patients have calcific stenosis (60% bicuspid, 10% tricuspid), 15% from rheumatic stenosis, and 15% from other forms of stenosis. Acquired aortic stenosis occurs as a result of arteriosclerotic degeneration and calcification of the aortic leaflets and usually manifests in the sixth, seventh, and eighth decades. According to the Helsinki Ageing study, almost 3% of the individuals aged between 75 and 86 years have critical aortic stenosis (1).

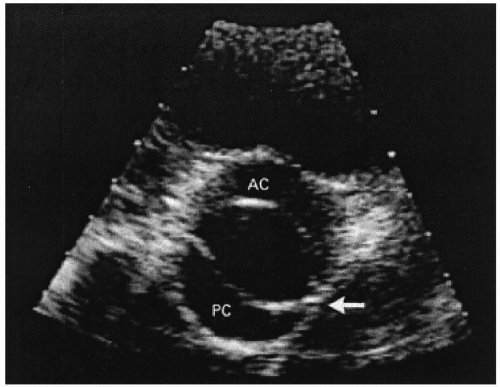

Approximately 1% of the population have bicuspid aortic valves (Figs. 24.2 and 24.3). Individuals with bicuspid aortic valves are more likely to develop aortic stenosis than are individuals with normal valves, and in such instances, the condition manifests in the third and fourth decades. The bicuspid aortic valve is the most common pathologic finding in symptomatic patients who are younger than 65 years (2). Bicuspid aortic valve is 4 times more common among men than among women. About one fifth of the patients with bicuspid aortic valves have associated cardiac abnormalities such as patient ductus arteriosus or coarctation of the aorta (3). The bicuspid aortic valve is not stenosed at birth, but it has a single fused commissure, which results in an eccentrically oriented orifice. These anatomic characteristics, when subjected to hemodynamic stress, may result in thickening and calcification of the valve leaflets, rendering them immobile. Many of these patients have associated abnormalities of the medial layer of the aorta above the bicuspid valve, predisposing to dilatation of the aortic root.

In developing countries, rheumatic fever is a common cause of aortic stenosis, and usually the valve also is regurgitant. The stenosis occurs in a previously normal valve and is characterized by the fusion of the commissures, followed by secondary calcification and contraction of leaflets and annulus. In these patients, the mitral valve is also almost always affected.

Aortic stenosis can coexist with other congenital cardiovascular defects such as coarctation of the aorta, in which the valve is often bicuspid (e.g., as in Turner syndrome); hypoplastic left heart syndrome; corrected

transposition of great arteries; ventricular septal defect with or without pulmonary stenosis; and coarctation of the aorta with a patent ductus arteriosus.

transposition of great arteries; ventricular septal defect with or without pulmonary stenosis; and coarctation of the aorta with a patent ductus arteriosus.

TABLE 24.1. Usual causes of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SYMPTOMS

Many patients with aortic stenosis are asymptomatic. Symptoms usually manifest when the valve area is less than 50% (normal valve area is 2 to 3 cm2). Typical symptoms of aortic stenosis include angina, syncope, and shortness of breath.

Angina occurs in about 70% of patients and, when coronary arteries are normal, results from a combination of increased myocardial oxygen demand and reduced coronary flow reserve caused by increased left ventricular mass. In one study, about one fourth of the patients with severe aortic stenosis had angiographically significant coronary artery disease (4).

Syncope occurs in about 25% of patients and often occurs during or immediately after exercise (see Chapter 5). Exertional syncope has been attributed to the fact that cardiac output is restricted by the stenosed valve, when peripheral resistance decreases on exercise. Impaired vasodepressor response

is a second explanation for syncope that occurs in this condition. Increased intramural pressure, stimulating baroreceptors and thereby resulting in reflex bradycardia and vasodilatation, is another mechanism by which syncope can occur. Diastolic dysfunction with inability to increase cardiac output on exercise is an additional mechanism. When the calcification of the aortic valve extends into the upper part of the ventricular septum, complete atrioventricular block can occur and manifests as syncope.

is a second explanation for syncope that occurs in this condition. Increased intramural pressure, stimulating baroreceptors and thereby resulting in reflex bradycardia and vasodilatation, is another mechanism by which syncope can occur. Diastolic dysfunction with inability to increase cardiac output on exercise is an additional mechanism. When the calcification of the aortic valve extends into the upper part of the ventricular septum, complete atrioventricular block can occur and manifests as syncope.

FIGURE 24.2. Bicuspid aortic valve (From: Bruce CJ, Breen JF. Aortic coarctation and bicuspid aortic valve. N Engl J Med 2000;342:249, with permission.) |

Shortness of breath results from high end-diastolic pressures in the left ventricle and is first apparent on exertion. Shortness of breath, including paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, is suggestive of left ventricular dysfunction and portends a poor prognosis. Orthopnea indicates severe left ventricular dysfunction. The left ventricular dysfunction, in aortic stenosis, is diastolic, systolic, or both. Diastolic dysfunction tends to predominate in advanced stages. Diastolic dysfunction is caused by increased left ventricular myocardial thickness, whereas systolic dysfunction is caused by increased dilatation of the left ventricle and decreased myocardial contractility. Severe aortic stenosis can manifest for the first time as congestive heart failure, and affected patients typically have a low-volume pulse, an enlarged heart, and a soft murmur. Heart failure is not an uncommon presentation (5), and such patients frequently have normal left ventricular systolic function.

Other modes of presentation include infective endocarditis (see Chapter 20), sudden death, and, occasionally, systemic emboli from the calcified valve (usually resulting in a stroke or amaurosis fugax). About 3% to 5% of patients with aortic stenosis die suddenly without prior symptoms, and the mechanism of death remains unclear, but it has been suggested that it may be a result of extreme intolerance to complete heart block or tachyarrhythmias. In patients with severe aortic stenosis, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia may develop as a result of hemolysis at the valve. Infective endocarditis should be considered in patients with aortic stenosis who have unexplained illness. Arrhythmias and

conduction abnormalities have also been described in aortic stenosis. Ventricular arrhythmias are more common than supraventricular arrhythmias, and heart block may occur because of calcification of conducting tissues.

conduction abnormalities have also been described in aortic stenosis. Ventricular arrhythmias are more common than supraventricular arrhythmias, and heart block may occur because of calcification of conducting tissues.

SIGNS

In mild aortic stenosis (when the aortic gradient is less than 50 mm Hg), the pulse is normal. In severe aortic stenosis, the carotid pulse is slow in increasing and has

diminished volume with a notch on the upstroke—the anacrotic pulse—but it may be normal in elderly patients with noncompliant carotid arteries. With associated aortic regurgitation, a double pulse, or pulsus bisferiens, may be felt. The apex beat initially is thrusting and not displaced and reflects the concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle. A displaced apex beat indicates left ventricular dilatation, which suggests that the condition is advanced or that associated aortic regurgitation is present. A

systolic thrill may be felt at the base of the heart.

diminished volume with a notch on the upstroke—the anacrotic pulse—but it may be normal in elderly patients with noncompliant carotid arteries. With associated aortic regurgitation, a double pulse, or pulsus bisferiens, may be felt. The apex beat initially is thrusting and not displaced and reflects the concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle. A displaced apex beat indicates left ventricular dilatation, which suggests that the condition is advanced or that associated aortic regurgitation is present. A

systolic thrill may be felt at the base of the heart.

On auscultation, a midsystolic, crescendo-decrescendo murmur (diamond-shaped murmur) is found, best heard in the second right intercostal space, and the intensity of the murmur increases on expiration. The murmur usually radiates to the neck and right clavicle. Clavicular auscultation appears to be more rewarding than the traditional search for transmission of aortic murmurs to the carotid artery (6). In mild aortic stenosis, the peak of the murmur occurs earlier in systole, and as the severity of stenosis progresses, the peak of the murmur occurs later in systole. The decrease in the loudness of the murmur is suggestive of the onset of poor left ventricular function and a low cardiac output. The murmur may display the Gallavardin phenomenon—that is, the selective transmission of the musical component toward the cardiac apex but location of the noisy component (jet noise) to the right of the upper sternum, with transmission toward the carotid arteries. The transmission of these high-frequency components of the murmur to the apex may be mistaken for mitral regurgitation.

The aortic component of the second heart sound is soft or absent when the valves are calcified. A delayed aortic component of the second sound or reverse split is suggestive of severe aortic stenosis. An ejection click may be heard at the apex in bicuspid aortic stenosis, especially in young patients. A third sound implies severe left ventricular dysfunction, whereas a fourth heart sound indicates severe aortic stenosis. Clinical signs of severe aortic stenosis include narrow pulse pressure, soft second heart sound, delayed or reverse split of second heart sound, heaving apex beat, fourth heart sound, and cardiac failure.

HELPFUL TESTS

Electrocardiogram

The electrocardiogram usually shows left ventricular hypertrophy and, occasionally, left axis deviation. In later stages, negative P waves may occur in lead V1 caused by left atrial hypertrophy. First-degree heart block or left bundle-branch block is suggestive of calcification of the conducting tissues. The presence of atrial fibrillation is suggestive of associated mitral valve disease or coronary artery disease.

Chest Radiograph

The chest radiograph may show cardiac enlargement, but, typically in the initial stages, the cardiac size may be normal in posteroanterior views. Poststenotic dilatation of the aorta may be seen but can also occur with subvalvular stenosis. Calcification of the aortic valve may be seen in lateral views, particularly in older patients. Signs of pulmonary venous congestion or pulmonary edema may be seen in acute left ventricular failure. When these signs are associated with coarctation of aorta, rib notching may be present.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography may show bicuspid valve (Figs. 24.2 and 24.3), calcified valve, left ventricular hypertrophy, and systolic function (Table 24.2). Women have a much higher incidence of excessive left ventricular hypertrophy, which leads to a supernormal left ventricular ejection fraction (7). Echocardiography is useful in the diagnosis and assessment of severity of aortic stenosis. Complete assessment of AS requires (a) measurement of transvalvular flow, (b) determination of the mean transvalvular pressure gradient, and (c) calculation of the effective valve area. The degree of aortic stenosis is graded as mild (valve area exceeding 1.5 cm2), moderate (area exceeding 1.0 to 1.5 cm2), or severe (area less than 1.0 cm2) (Table 24.3).

Echocardiography also helps define the level of obstruction (i.e., valvular, supravalvular, subvalvular). A normal valve appearance excludes significant aortic stenosis in adults. Furthermore, echocardiography allows assessment of left ventricular size, function, and hemodynamics. It is useful in the reevaluation of patients with known aortic stenosis

with changing symptoms and signs and in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis. Doppler imaging allows assessment of the valve gradient. The valve gradient, however, depends on several factors, including left ventricular function, and therefore is not a good indicator of the severity of the disease. For example, a mean valve gradient of less than 50 mm Hg may be associated with severe, moderate, or even mild aortic stenosis (8,9). Thus it is more prudent to use the effective aortic valve area to determine the severity of aortic stenosis. This may be assessed by the continuity equation.

with changing symptoms and signs and in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis. Doppler imaging allows assessment of the valve gradient. The valve gradient, however, depends on several factors, including left ventricular function, and therefore is not a good indicator of the severity of the disease. For example, a mean valve gradient of less than 50 mm Hg may be associated with severe, moderate, or even mild aortic stenosis (8,9). Thus it is more prudent to use the effective aortic valve area to determine the severity of aortic stenosis. This may be assessed by the continuity equation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree