35 Aortic Regurgitation

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Aortic Valve Leaflet Pathology

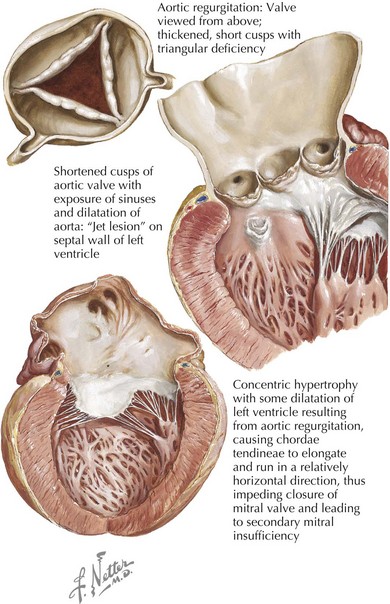

Causes of valve leaflet disease include rheumatic heart disease, congenital abnormalities of the aortic valve (especially bicuspid valves), calcific degenerative valve disease, myxomatous degeneration, or infective endocarditis. Rheumatic disease is characterized by shortening and scarring of the cusps and is frequently accompanied by mitral valve involvement (Fig. 35-1). Congenitally bicuspid valves are found in 1% to 2% of the population, with a 3 : 1 male predominance. There is a growing appreciation that the presence of a bicuspid valve is linked to a connective tissue disorder that leads to loss of elastic tissue within the proximal aorta, ultimately predisposing to aortic root dilatation and an increased propensity to dissection. While a bicuspid valve often presents as aortic stenosis or a mixed stenosis-regurgitation lesion, 10% of individuals with bicuspid aortic valves have pure regurgitation, occurring as a result of altered cusp architecture or an abnormal aortic root related to annular dilatation or dissection. Infective endocarditis may cause aortic regurgitation by several mechanisms, including (1) perforation of a single leaflet or a flail leaflet and (2) weakening of the cusp and valve annulus as a result of an expanding aortic root abscess.

Aortic Root Diseases

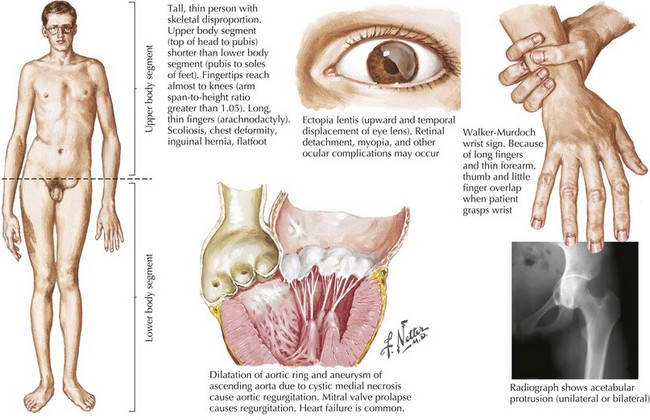

Aortic root disease is responsible for approximately one half of all clinically significant cases of aortic regurgitation. Common aortic root problems causing aortic regurgitation include connective tissue disorders (such as Marfan’s syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and type IV Ehler-Danlos) that may lead to annuloaortic ectasia or ascending aortic dissection and resulting distortion of valve structure and/or undermined support of the aortic valve leaflets (Fig. 35-2). In long-standing systemic hypertension, aortic regurgitation may occur from dilatation of the ascending aorta with distortion of the valve and chronic damage to the valve leaflets.

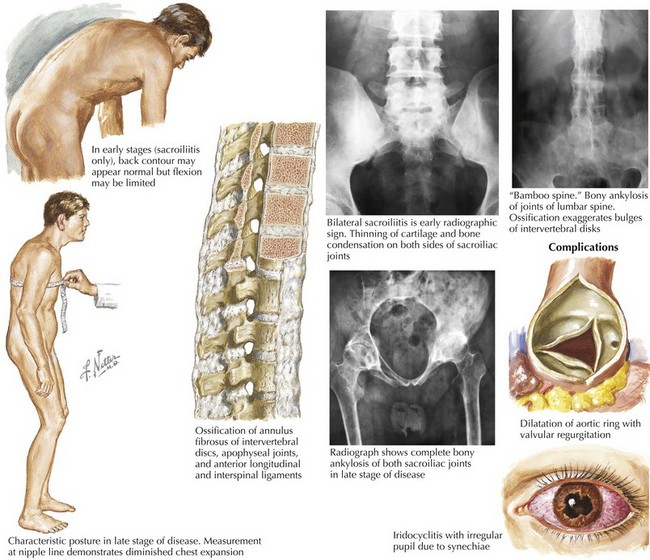

Less common causes of aortic regurgitation include syphilitic aortitis, ankylosing spondylitis, osteogenesis imperfecta, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, Behçet’s syndrome, ulcerative colitis, discrete subaortic stenosis, and ventricular septal defect with prolapse of an aortic cusp (Fig. 35-3).

Clinical Presentation

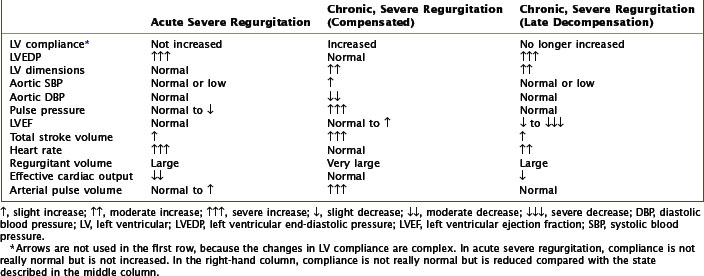

Clinical presentation of aortic regurgitation varies with the onset (acute or chronic) and the degree to which compensatory changes have occurred within the left ventricle in response to volume overload (Table 35-1). In acute aortic regurgitation the presentation is usually dramatic. LV compensatory dilatation has not yet developed, so LV compliance is normal and remains so despite the sudden regurgitation. The acute volume overload is poorly tolerated, because the left ventricle is abruptly and markedly distended, resulting in impaired systolic function (based on the Frank-Starling mechanism). As a result, the left ventricle functions on the steep portion of the pressure-volume curve, leading to a considerably increased LV diastolic pressure, which in turn causes a severe increase in left atrial and pulmonary capillary wedge pressures, with resultant pulmonary edema. Forward cardiac output is reduced, and sinus tachycardia develops in an attempt to augment cardiac output. The regurgitation causes premature mitral valve closure with occasional diastolic mitral regurgitation. Because of these changes, the patient with acute aortic regurgitation usually appears severely ill, manifesting tachycardia, hypotension, peripheral vasoconstriction, and pulmonary edema, but lacks many of the physical signs of chronic regurgitation. Fatigue, apathy, agitation, or a decline in mental function may develop as a manifestation of the decrease in forward cardiac output. Finally, patients may develop signs and symptoms of myocardial ischemia due to the combination of a lower aortic diastolic blood pressure and increased LV end-diastolic pressure resulting in a reduced transmyocardial pressure gradient to support coronary blood flow.

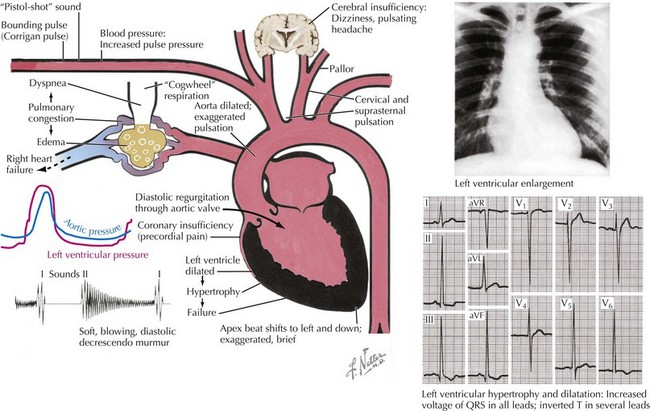

Chronic aortic regurgitation may be asymptomatic for years. When symptoms develop, they are usually indolent, reflecting the disease’s slow, progressive nature. Frequent complaints include exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and palpitations. Angina pectoris may occur if there is significant coronary artery disease or because of reduced coronary blood flow in the setting of LV hypertrophy. As in acute aortic regurgitation, a reduced transmyocardial perfusion pressure exists that reduces coronary blood flow. This is further worsened by the degree of LV hypertrophy, which increases myocardial oxygen demand. As aortic regurgitation develops, the left ventricle slowly enlarges primarily with eccentric hypertrophy, although concentric hypertrophy also occurs from increased afterload (Fig. 35-4). As the regurgitation progresses, the left ventricle slowly dilates with an increase in end-diastolic volume and chamber compliance. Accordingly, in the early phases of LV dilation before the onset of systolic dysfunction, the increased end-diastolic volume is not associated with major increases in end-diastolic pressure. The resulting increased stroke volume maintains a normal forward cardiac output, usually without substantial increases in heart rate. The augmented stroke volume leads to many of the classic findings of chronic aortic regurgitation (Table 35-2; see Fig. 35-4). Occasionally, patients may experience an unpleasant awareness of each contraction, especially if irregular beats lead to a diastolic pause with a larger stroke volume in the subsequent beat. The augmented aortic systolic pressure from the increased stroke volume plus the lower aortic diastolic pressure from regurgitation into the left ventricle results in a wide pulse pressure. During exercise, systemic vascular resistance and diastolic filling period decrease, resulting in less regurgitation per cardiac cycle. This increases forward cardiac output without substantial increases in LV end-diastolic pressure. With time and worsening aortic regurgitation, the ability of the left ventricle to compensate for the chronic volume overload eventually is exceeded, and LV systolic failure develops. As the LV ejection fraction decreases, the ventricle dilates further, initiating a vicious cycle eventually leading to the typical symptoms of congestive heart failure. Throughout this process, myocardial fibrosis contributes to the gradual development of irreversible LV dysfunction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree