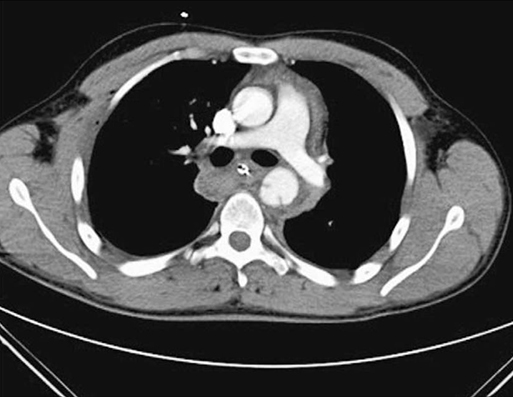

Aortic trauma is most common in men between the ages of 20 and 40 years. In 1989, Mattox and colleagues reported that 90% of cardiovascular trauma was caused by penetrating mechanisms and only 7% was caused by blunt injury. The descending thoracic aorta is the one anatomic location where blunt mechanism is nearly as common (44%) as penetrating trauma (56%). The higher incidence of injury in the descending thoracic aorta is as a result of its relatively fixed nature at the ligamentum arteriosum, which, as the remnant of the ductus arteriosus, connects the pulmonary artery to the inferior surface of the aortic arch. In cases of thoracic trauma with significant deceleration, this anatomic relationship predisposes the proximal portion of the descending thoracic aorta to tears in the wall of the vessel (Figure 1). The majority of blunt aortic injuries occur at the aortic isthmus, which is an area of slight constriction immediately distal to the left subclavian artery origin at the point of attachment of the ligamentum arteriosum (see Figure 1). In a classic 1958 report, Parmley described the direct, indirect, deceleration, compression, and blast forces that produce aortic rupture. Direct forces include displacement of the vertebrae that cause rupture of the aorta by shearing forces. Indirect forces act through a sudden and significant increase of pressure within the aorta. In cases of significant trauma, patients who remain hemodynamically normal undergo contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the aorta. In most studies, aortic CT has been shown to have near 100% sensitivity and negative predictive value (Figure 2). If the CT scan raises question of an aortic injury, traditional contrast aortography is indicated (see Figure 1). Recognizing that not all blunt aortic injuries are the same, Starnes and colleagues have performed multiple studies to advance understanding of the natural history based on CT imaging. Specifically, this group created a novel classification system based on the presence or absence of aortic external contour abnormality, defined as an alteration in the symmetric, round shape of the aorta (Box 1). The grades of aortic injury are intimal tear without an external contour abnormality and an intimal defect and or thrombus of less than 10 mm of length or width; large intimal flap without an external contour abnormality and intimal defect and/or thrombus of greater than 10 mm of length or width; pseudoaneurysm with an external contour abnormality and contained rupture; and rupture with an aortic external contour abnormality and contrast extravasation. This grading allows one to characterize mortality and make recommendations regarding the timing of appropriate management strategies for patients with blunt aortic injury.

Aortic Injury

Incidence

Pathophysiology

Presentation and Diagnosis

Aortic Injury