Chapter 53 Anus

Disorders of the Anal Canal

Anatomy

Anal Canal Musculature

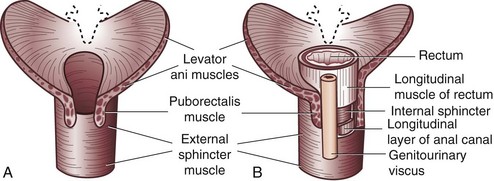

The anal canal musculature, with its sphincteric apparatus, is the terminal muscular channel of the gastrointestinal tract and can be conceptualized as two tubular structures overlying each other. The inner component is the continuation of the smooth circular layer of the rectum forming the thickened and rounded internal sphincter, which ends 1.5 cm below the dentate line, slightly cephalad to the external sphincter (intersphincteric groove). The outer component is a continuous sheet of striated muscle constituting the pelvic floor, which is comprised of the levator ani muscle, puborectalis muscle, and external sphincter (Fig. 53-1). The latter is elliptical and engulfs the anal canal and internal sphincter, beyond which it terminates in a subcutaneous portion. The other two portions, the superficial and deep divisions, constitute a single muscular unit, which is continuous superiorly with the puborectalis and levator ani muscles. The external sphincter, bulbospongiosus, and transverse perineal muscles meet together centrally on the perineum and constitute the perineal body. The funnel-shaped configuration of the paired levator ani muscles form the major part of the pelvic floor and their fibers decussate medially with the contralateral side to fuse with the perineal body around the prostate or vagina.

Anal Canal Lining

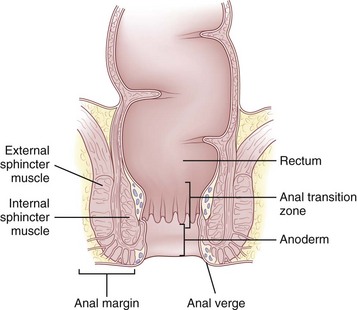

The epithelium that lines the anal canal incrementally transitions from normal, squamous, hair-bearing skin to gastrointestinal columnar epithelium in the short distance between the anal verge and top of the anal canal (Fig. 53-2). At the verge, the skin becomes anoderm, which is a modified squamous lining without skin appendages, such as hair. At the level of the dentate line, the squamous and columnar epithelium comingle; this is referred to as the anal transition zone. Finally, cephalad to the top of the anal canal, the lining becomes exclusively gastrointestinal columnar epithelium. These epithelial distinctions are helpful for understanding the basis and treatment of benign and malignant conditions. For example, fistulas developing from the condition of hidradenitis suppurativa can only arise from the appendages of skin, so this disorder can only occur below the dentate line, typically outside the anal verge. In contrast, fistulas that are derived from crypto glandular disease arise within the glands at the level of the dentate line and Crohn’s fistulas typically arise in the gastrointestinal tract above the dentate line. These distinctions help differentiate the diagnoses. For cancer cases, the histology is the key to understanding the likely origin, behavior, and management of the disease. Squamous cell lesions that arise in the anal margin skin or anoderm are treated with wide excision as skin cancers (margin lesions) or with radiation chemotherapy (anal canal). Adenocarcinomas arising in the distal rectum or within the anal canal are usually treated with surgical removal of the rectum, with the adjunctive use of radiation and chemotherapy.

Physiology

The physiology of the anal canal and pelvic floor is complex, but the advent of more sophisticated means to evaluate its functions (e.g., manometry, defecography, evacuability testing, electromyography) has improved our understanding of it. The principal function of the anal canal is the regulation of defecation and maintenance of continence. The ability to control defecation depends on the coordinated functions of the sensory and muscular activities of the anus, the compliance, tone, and evacuability of the rectum, the muscular activities of the pelvic floor, and the consistency, volume, and timing of the colonic fecal movements. Perturbations of any of the critical functions can result in fecal incontinence (Table 53-1).

Table 53-1 Common Causes of Fecal Incontinence

| CATEGORY | MECHANISM | COMMON CAUSES |

|---|---|---|

| Functional | Fecal impaction; dilated internal anal sphincter | Pelvic floor dyssynergia (difficulty relaxing sphincter when defecating), drug side effect, idiopathic, spinal cord injury |

| Diarrhea; rapid transit and/or large volume | Irritable bowel syndrome; infectious and metabolic causes of diarrhea | |

| Cognitive, psychological; social indifference | Dementia, psychosis, willful soiling | |

| Sphincter weakness | Sphincter muscle injury | Obstetric trauma, motor vehicle accident, foreign body trauma |

| Pudendal nerve injury | Obstetric trauma, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, idiopathic | |

| Central nervous system injury | Spina bifida, traumatic spinal cord injury, cerebrovascular accident, multiple sclerosis | |

| Sensory loss | Afferent nerve injury: unable to detect rectal filling | Diabetic neuropathy, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis |

Adapted from Whitehead WE, Wald A, Norton NJ: Treatment options for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 44:131–142, 2001.

Pelvic Floor Disorders

Incontinence

A National Institutes of Health (NIH) State-of-the-Science Conference on the Prevention of Fecal and Urinary Incontinence in Adults was conducted in 2007.1 Several important conclusions were reached, including that fecal and urinary incontinence will affect more than 25% of all U.S. adults during their lives. Fecal incontinence is now recognized as having serious effects, causing people to suffer physical discomfort, embarrassment, stigma, and social isolation. Furthermore, the panel concluded that financial costs and caregiver burden are substantial and may be underestimated because of underreporting.

Clinical Evaluation

Determining the extent and nature of the problem should start by distinguishing true incontinence (i.e., complete loss of solid stools) from minor incontinence (i.e., occasional staining from seepage or urgency). Seepage of mucus from prolapsing hemorrhoids or from a large secretory villous polyp, urgency from colitis or proctitis, and overflow incontinence from fecal impaction may be confused with true incontinence. After true incontinence is established, the severity of the disability should be assessed by seeking information on control of flatus, liquid and solid stool, and effect on lifestyle and activities (see Table 53-1).2

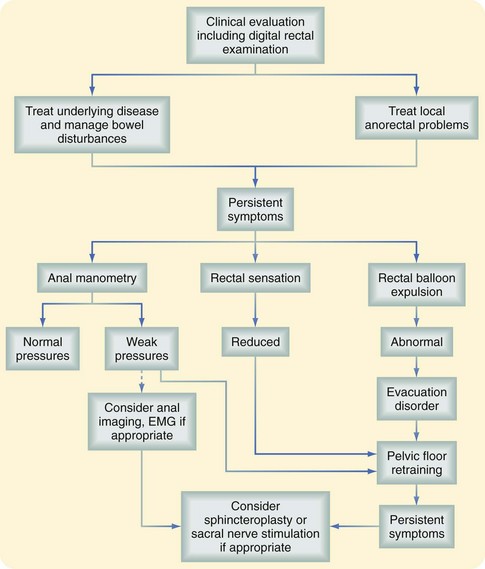

Fecal incontinence is often multifactorial; defects in the sphincter may be the result of trauma from previous surgical procedures for hemorrhoids, fissures, or fistulas, forceful dilation of the anal canal, impalement injury, or obstetric injuries, either directly because of a tear or breakdown of episiotomy repair or indirectly from stretching of the pudendal nerve during labor, which may develop decades later. The NIH consensus panel concluded that for fecal incontinence, a routine episiotomy is the most preventable risk factor, but that additional risk factors include female gender, older age, and neurologic diseases, with contributions also from body mass, decreased activity, depression, and diabetes. The workup of fecal incontinence should include an evaluation of associated gastrointestinal disorders, such as diarrhea, which can aggravate disorders of continence (Fig. 53-3).3 The physical examination should confirm a weak resting tone and squeeze pressure or a patulous anus and the presence of scars, defects, deformities, or keyhole abnormalities. Examination can also exclude the presence of prolapse, hemorrhoids, or other contributory or associated anorectal abnormalities. Endoscopy excludes the diagnoses of proctitis, fecal impaction, rectal polyps, and colitis cystica profunda.

FIGURE 53-3 Clinical evaluation of fecal incontinence. EMG, Electromyogram.

(From Whitehead W, Bharucha AE: Diagnosis and treatment of pelvic floor disorders: What’s new and what to do. Gastroenterology 138:1231–1235, 2010).

Additional testing can be restricted to a few tests, depending on the extent of findings at examination.4,5 Anal manometry confirms the extent of impairment of the internal and external sphincters by the resting and squeeze pressures, respectively. Manometry can also identify asymmetry, suggesting anatomic defects amenable to repair. Endoanal ultrasound has been recommended to detect occult defects and, in some centers with expertise, is considered more accurate than clinical or conventional methods of evaluation. Finally, electromyography of the pelvic floor can be used to differentiate between anatomic and neurogenic sources of incontinence, and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency testing can predict the likelihood of successful repair.

Treatment

Medical Management

Medical management is a preferred option for cases of mild incontinence and of generalized weakness in which reparable anatomic defects are not identified. A first-line approach includes the use of diet and medications to slow transit and increase stool consistency. Coupled with sphincter exercises, this may improve symptoms and restore normal function for mild cases.4 Biofeedback training focuses on strengthening of the anal musculature and improving anorectal sensation and is reported with variable success rates of approximately 75% for at least modest reduction in incontinence frequency, with 50% accomplishing complete continence. A bowel management program has been a successful approach for patients with anorectal malfunctions, Hirschsprung’s disease, and spina bifida.6 Of note, medical management can also be considered complementary to surgical therapy and may be carried out before and/or after surgery to optimize surgical results.

Surgical Repair

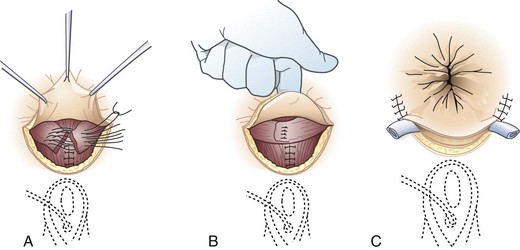

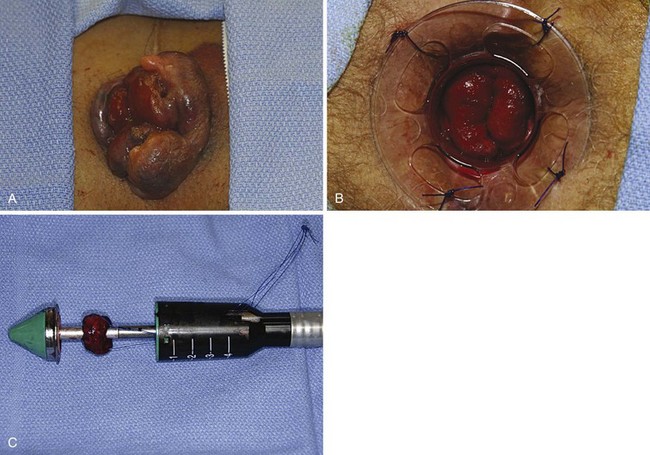

Surgical options range from the traditional approach of sphincter repair to the newer technique of sacral nerve stimulation and to the final step of colostomy creation. For discrete anatomic defects, the most common surgical approach is the direct overlapping sphincteroplasty, in which the separated muscular ends are dissected, reapproximated, and sutured (Fig. 53-4).7 Fecal diversion is not typically required for these repairs unless there are extenuating circumstances. The overlapping sphincteroplasty is associated with low rates of morbidity and mortality and reasonable rates of success with good to excellent results achieved in 55% to 68% of patients.4 Direct repair of anterior sphincter defects from obstetric injuries can be expected to restore fecal continence in 59% of patients. A study of 10-year outcomes after anal sphincter repair has suggested continued deterioration of function over time. For nonanatomic defects, postanal repair is advocated by some surgeons but reserved for highly select patients.

Prolapse of the Rectum

Preoperative Evaluation

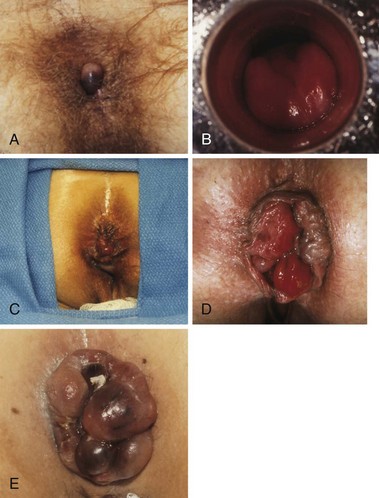

The preoperative assessment of the patient should focus on establishing the extent of the prolapse, patient’s overall health status, presence of associated conditions, such as constipation and pelvic floor disorders, and complications, such as incontinence. All these factors influence the operative and medical management. At history, almost 50% of patients have constipation and most have fecal incontinence.8,9 By observing the patient while he or she is straining on the commode, the presence and extent of the prolapse can be verified. Complete prolapse demonstrates full-thickness rectal protrusion with concentric rings (Fig. 53-5). Frail older patients and those with high-risk comorbid conditions or limited life expectancy are ideally suited for perineal procedures. Younger patients, particularly those with constipation or evidence of pelvic floor defecating disorders, are best served with resection and fixation using open or laparoscopic approaches.

Surgical Correction

Perineal Procedures

The Delorme procedure is essentially a mucosal proctectomy and muscularis plicating procedure (Fig. 53-6). It is ideally applied to patients with up to 3 to 4 cm of prolapse, even though the mucosal tube resected can extend up to 15 cm. Even in frail older patients, the Delorme procedure is associated with low rates of mortality and major morbidity, approximately 1% and 14%, respectively.9 Incontinence improves in as many as 69% of patients. Prolapse recurrence is not uncommon and is likely underestimated because this procedure is performed in patients with limited life expectancies and therefore short follow-up.

The Altemeier procedure is similar to the Delorme procedure, but rather than a mucosal resection, a full-thickness rectal resection is performed, starting 1 or 2 cm above the dentate line. The bowel and attendant mesentery are resected. Because the pelvic cavity is entered, injury to the small bowel must be avoided. A full-thickness anastomosis is accomplished after the full extent of resection is completed. For patients with incontinence, a levatorplasty may be added to the resection. Results are similar to those described for the Delorme procedure.8

Abdominal Procedures

The abdominal options include bowel resection and rectopexy, with or without mesh, performed alone or together. Complete mobilization of the rectum is required for the abdominal procedures; debate exists about whether the lateral stalks should be preserved.10 Preservation of the stalks is thought to yield better functional results but a greater risk for recurrence. Although the entire rectum is mobilized to the level of the levatores, if resection and anastomosis are being performed, they should be performed high rather than low in the rectum, essentially an anterior resection. This minimizes the risk for anastomotic complications. Rectopexy is performed by securing the rectum to the presacral tissues. Resection with rectopexy is associated with low recurrence rates (0% to 9%) and can be performed safely, with morbidity and mortality rates commensurate with any large bowel resection. Constipation improves in up to 50% of patients and incontinence in most patients.

Rectocele

Clinical Evaluation

Patients with a rectocele present with a bulge or prolapse of the anterior rectal wall into the vagina. Symptoms attributable to a rectocele include the presentation of a vaginal bulge, inability to evacuate completely during defecation and, in most cases, the necessity to evacuate digitally through the vagina or through the rectum or perineum. The cause of rectoceles remains unclear; it is probably multifactorial because it is associated with a constellation of a number of pelvic floor disorders, including constipation, paradoxical muscular contraction, and neuropathies or anatomic disorders from childbirth.11 Rectocele may coexist with other defecation disorders, such as slow-transit constipation or pelvic floor dysfunction, including pelvic organ prolapse, in which factors such as age, parity, obesity, constipation, pelvic surgery, and pulmonary and medical conditions may play a role. Associated disorders must be addressed to achieve resolution of all symptoms. A careful physical examination will reveal the size of the defect where the rectum prolapse extends to the vagina.

Defecography, which can demonstrate dynamic information on the process of rectal emptying, is the only test that is specifically diagnostic for a rectocele.11 It is probably the most useful test for understanding the relevance of the rectocele in the defecation process, even though there is no exact correlation between any single test finding and results from surgery. Further colorectal evaluations and tests can be ordered, as appropriate, for other symptoms or coexisting disorders.

Treatment

The optimization of bowel function through proper diet, fiber supplements, and good bowel habits is always appropriate as complementary therapy. Medical therapies, specifically biofeedback, have met with limited success, providing only partial relief in most patients but major relief in only a minority of patients.12

Surgical Treatment

Patients with rectoceles should be considered for surgical correction if the rectocele is larger than 2 cm and the patient has to perform digitally assisted defecation.13 Although gynecologic surgeons often perform a transvaginal repair, the defect between the vagina and rectum can be corrected using a transperineal approach, with or without mesh and including a levatorplasty, or using a transanal repair, with an anal mucosa flap and a plication technique without mesh. The repair should extend 7 to 10 cm above the anal canal. Symptomatic improvement can be anticipated in 73% to 79% of properly selected patients. Best results can be expected in patients who have a small rectocele, require digitally assisted evacuation, are without evidence of anismus, and can be repaired using a transperineal approach.

Common Benign Anal Disorders

Hemorrhoids

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Evaluation

Within the normal anal canal there are specialized, highly vascularized cushions forming discrete masses of thick submucosa containing blood vessels, smooth muscle, and elastic and connective tissue. They are located in the left lateral, right anterior, and right posterior quadrants of the canal to aid in anal continence. The term hemorrhoids should be restricted to clinical situations in which these cushions are abnormal and cause symptoms. The cause of hemorrhoids remains unknown. They may be no more than the downward sliding of anal cushions associated with gravity, straining, and irregular bowel habits. Hemorrhoids can be considered external or internal; the diagnosis is based on the history, physical examination, and endoscopy. External hemorrhoids are covered with anoderm and are distal to the dentate line; they may swell, causing discomfort and difficult hygiene, but cause severe pain only if actually thrombosed. Internal hemorrhoids cause painless, bright red bleeding or prolapse associated with defecation. Internal hemorrhoids are classified according to the extent of prolapse, which influences treatment options (Table 53-2). The patient may report dripping or even squirting of blood in the toilet bowl. Chronic occult bleeding leading to anemia is rare, and other causes of anemia must be excluded. Prolapse below the dentate line area can occur, especially with straining, and may lead to mucus and fecal leakage and pruritus. Pain is not usually associated with uncomplicated hemorrhoids but more often with fissure, abscess, or external hemorrhoidal thrombosis.

Table 53-2 Internal Hemorrhoids: Grading and Management

| GRADE | SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS | MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|---|

| First degree | Bleeding; no prolapse | Dietary modifications* |

| Second degree | Prolapse with spontaneous reduction | Rubber band ligation |

| Bleeding, seepage | Coagulation Dietary modifications | |

| Third degree | Prolapse requiring digital reduction | Surgical hemorrhoidectomy |

| Bleeding, seepage | Rubber band ligation Dietary modifications | |

| Fourth degree | Prolapsed, cannot be reduced | Surgical hemorrhoidectomy |

| Strangulated | Urgent hemorrhoidectomy Dietary modifications |

* Dietary modifications include increasing consumption of fiber, bran, or psyllium and water. Dietary modifications are always appropriate for the management of hemorrhoids, if not for acute care then for chronic management, and for prevention of recurrence after banding and/or surgery.

The physical examination should include inspection during straining, preferably on a commode, digital rectal examination, and anoscopy (Fig. 53-7). Digital examination enables assessment of internal and external hemorrhoidal disease and anal canal tone and exclusion of other lesions, especially low rectal or anal canal neoplasms. Because almost all anorectal symptoms are ascribed to hemorrhoids by patients, it is essential that other anorectal pathologies be considered and excluded. Anoscopy is the definitive examination, but a flexible proctosigmoidoscopy should always be added to exclude proximal inflammation or neoplasia. Colonoscopy or barium enema should be added if the hemorrhoidal disease is unimpressive, the history is somewhat uncharacteristic, or the patient is older than 40 years or has risk factors for colon cancer, such as a family history. Depending on the degree of disease, treatment falls into two main categories, nonsurgical and hemorrhoidectomy.

Treatment

Nonoperative Management

In many patients, hemorrhoidal symptoms can be ameliorated or relieved by simple measures, such as better local hygiene, avoidance of excessive straining, and better dietary habits supplemented by medication to keep stools soft, formed, and regular (see Table 53-2). A wide array of fiber supplements are now available over the counter. Symptoms of bleeding but not prolapse can be significantly reduced over a period of 30 to 45 days with the use of fiber supplements. Over-the-counter suppositories and anal salves, although popular, have never been tested for efficacy. Even though all patients should be counseled on dietary and fiber recommendations, patients with prolapse and internal plus external hemorrhoids benefit from additional interventions.

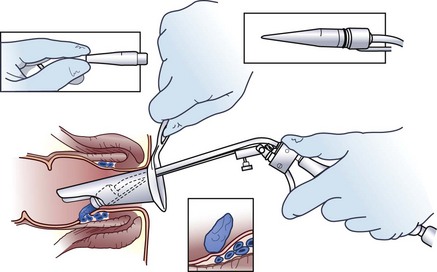

In the absence of symptomatic external hemorrhoids, second- and some third-degree internal hemorrhoids can be treated with office procedures that produce mucosal fixation. Although sclerotherapy, infrared coagulation, heater probe, and bipolar electrocoagulation have all been described, the simplest, most effective, and most widely applied office procedure is rubber band ligation. Rubber band ligation can be performed in the office without sedation through an anoscope, using a ligator (Fig. 53-8). Preferably, only one site should be banded each time. Because severe perineal sepsis and even deaths have been reported after rubber band ligation, patients should be instructed to return to the emergency department if delayed or undue pain, inability to void, or a fever develops. With one or more applications, symptoms are alleviated in 79% of patients.14 Because of the risk for bleeding and sepsis, it is preferable that patients not be taking antiplatelet or blood-thinning medications and that subacute bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis is administered to patients at risk. Rubber band ligation should be avoided in immunodeficient patients.

Surgical Treatment

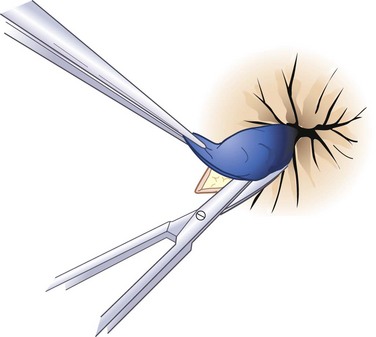

Hemorrhoidectomy is the best means of curing hemorrhoidal disease and should be considered whenever patients fail to respond satisfactorily to repeated attempts at conservative measures, hemorrhoids are severely prolapsed and require manual reduction, hemorrhoids are complicated by strangulation or associated pathology, such as ulceration, fissure, or fistula, or hemorrhoids are associated with symptomatic external hemorrhoids or large anal tags. The choice of anesthesia should be individualized based on the patient’s preference, build, and medical status. In most cases, local or regional anesthesia with mild sedation can be used effectively. For simple, thrombosed external hemorrhoids, excision in the office is best performed early in the course of the disease, during the period of maximum pain (Fig. 53-9). To remove complex internal or external hemorrhoids, an open or closed hemorrhoidectomy can be performed as an outpatient procedure.

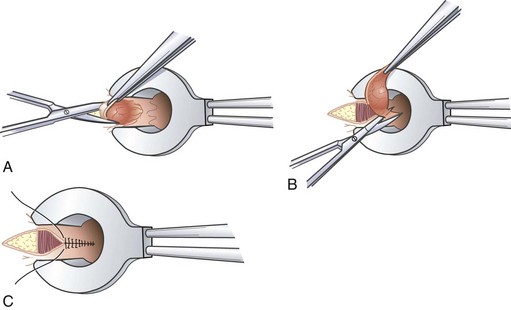

Closed hemorrhoidectomy provides simultaneous excision of internal and external hemorrhoids (Fig. 53-10). Preoperative and intraoperative assessment determines the number and location of hemorrhoids requiring excision; typically, three bundles are identified in the right anterior, right posterior, and left lateral positions. Using a large operative scope retractor, such as the Fansler, ensures that sufficient anoderm is preserved to avoid the long-term complication of anal stenosis. Postoperative complications include fecal impaction, infection, urinary retention and, rarely, arterial bleeding. Patients typically recover sufficiently to return to work within 1 to 2 weeks. As an alternative to the closed technique, the surgical wounds can be left open to reduce postoperative pain, but at the expense of longer healing times.

Newer technology and techniques have been applied to the operative treatment of hemorrhoids, with the promise of less postoperative pain. The two main categories of these treatments involve the application of ultrasonic or controlled electrical energy, such as the Harmonic Scalpel (Soma, Bloomfield, Conn) and LigaSure (Covidien, Boulder, Colo) respectively, or a new operative approach to hemorrhoidal tissue excision. Both energy application modalities remove the excess hemorrhoidal tissue and coagulate or seal the blood vessels simultaneously, with minimal lateral thermal injury to nearby tissue. It is thought that the reduction in trauma to the surrounding anal canal mucosa and underlying anal sphincter will decrease postoperative edema and pain. Small single-institution reports have evaluated both these newer technologies compared with traditional excisional hemorrhoidectomy.15 These studies all demonstrated decreased postoperative pain and analgesic use in the Harmonic Scalpel or Liga-Sure groups compared with traditional techniques, with similar short-term success rates.

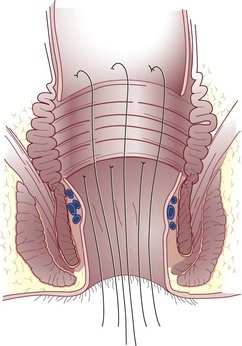

Another operative technique developed to treat circumferential prolapsed and bleeding hemorrhoids was first described by Longo. Thus technique, commonly referred to as the stapled hemorrhoidectomy or stapled hemorrhoidopexy, excises a circumferential portion of the lower rectal and upper anal canal mucosa and submucosa and performs a reanastomosis with a circular stapling device. As a result, the prolapsed anal cushions are retracted and fixed into their normal anatomic positions within the anal canal. Stapled hemorrhoidectomy is performed using a dedicated device, including an obturator and circular stapler (Fig. 53-11). To conduct the procedure, the hemorrhoidal tissue must first be reduced and the anal canal gently dilated to facilitate introduction of the stapler. A purse-string suture is placed 3 to 4 cm above the dentate line. Placement of this suture should incorporate all the redundant tissue circumferentially, with care being taken to avoid a full-thickness suture that would ensnare the vaginal wall in women. If the suture is placed too close to the dentate line, it could lead to severe and prolonged pain or urgency. If the suture is placed too far cephalad or does not include circumferential tissue incorporation, it will likely not resolve all symptoms.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree