General Considerations

Atherosclerosis is a leading cause of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerotic plaques can acutely rupture, exposing a necrotic core that sets off the coagulation cascade, ultimately culminating in vascular occlusion. Activation of platelets is the initial event in this cascade and, depending on the vascular bed involved, can cause acute coronary syndromes, ischemic stroke, mesenteric ischemia, or acute limb ischemia. Antiplatelet therapy forms the core of treatment for both acute and chronic atherosclerotic disease. In this chapter, we will discuss antiplatelet therapy in the treatment of cardiovascular disease.

Role of Platelets in Thrombosis

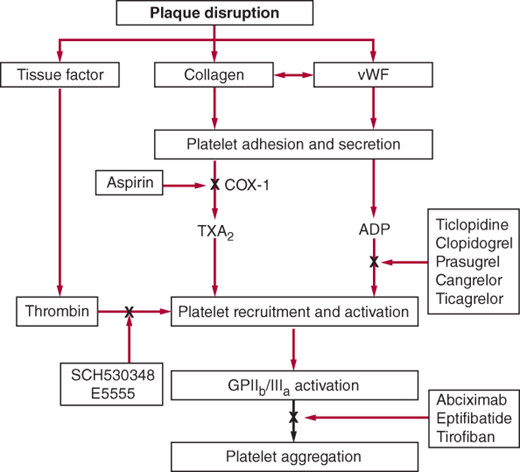

After vascular injury, platelets are bound to exposed collagen and von Willebrand factor (vWF) and activated. Activated platelets then secrete thromboxane A2 (TXA2) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP), which leads to platelet aggregation and recruitment of more platelets. The final common pathway of platelet aggregation is mediated by glycoprotein (GP) IIbIIIa receptors that bind to fibrinogen and vWF, leading to platelet plug and clot formation. Antiplatelet agents target different pathways in this cascade (Figure 3–1).

Figure 3–1.

Site of action of antiplatelet drugs. Aspirin inhibits thromboxane A2 (TXA2) synthesis by irreversibly acetylating cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1). Reduced TXA2 release attenuates platelet activation and recruitment to the site of vascular injury. Ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and prasugrel irreversibly block P2Y12, a key adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor on the platelet surface; cangrelor and ticagrelor are reversible inhibitors of P2Y12. Abciximab, eptifibatide, and tirofiban inhibit the final common pathway of platelet aggregation by blocking fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor (vWF) binding to activated glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa. SCH530348 and E5555 inhibit thrombin-mediated platelet activation by targeting protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1), the major thrombin receptor on human platelets. (Reproduced with permission from Longo DL, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.)

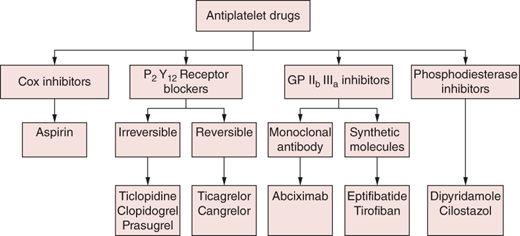

Classification of Antiplatelet Drugs

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, aspirin) in low doses irreversibly inhibits cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), which is required for synthesis of TXA2, a vasoconstrictor required for platelet aggregation. At higher doses, ASA also inhibits COX-2, which is required for prostacyclin production; prostacyclins are inhibitors of platelet aggregation and vasodilators. Thus, for optimal antiplatelet effect, an ASA dose between 75 and 325 mg is recommended. For rapid onset of action, in ASA-naïve patients, a dose of at least 162 mg should be used.

ASA is contraindicated in patients with a history of bronchospasm or anaphylactic reaction.

Dyspepsia, peptic ulcer, erosive gastritis, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding are dose-related side effects. Some patients may develop bronchospasm, urticaria, and rarely anaphylactic reactions. Complex acid–base abnormalities can occur in the setting of aspirin overdose. Some younger patients may have aspirin hypersensitivity with associated nasal polyps, allergic rhinitis, and bronchospasm (Samter’s triad). These patients may benefit from aspirin desensitization. Hyporesponsiveness to ASA is defined as the inability of ASA to produce expected inhibitory effects on platelet function. Clinically, this is associated with increased vascular events. Currently, there is no consensus on treatment, although empirically, an ADP receptor antagonist may be added.

All patients who present with chest pain and electrocardiographic or cardiac biomarker evidence of ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-STEMI (NSTEMI) should be treated with non–enteric-coated aspirin 162–325 mg (preferably crushed and chewed to enable rapid onset of action). Aspirin should be continued indefinitely in all patients who are not allergic at a dose of 75–162 mg/day, once daily. For patients allergic to aspirin, clopidogrel (or another P2Y12 receptor antagonist) is a reasonable alternative.

Aspirin 75–162 mg is a standard component of routine management of patients with chronic stable angina and has been demonstrated to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Patients with symptomatic lower extremity peripheral arterial disease have a high likelihood of disease in other vascular beds and should be treated with aspirin to reduce risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or vascular death.

Patients with prior ischemic stroke or TIA should receive aspirin 325 mg within the first 48 hours of onset of symptoms. If the patient has received thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke, antiplatelet therapy can be started after 24 hours. Therapy should be continued indefinitely at a dose of 75 or 81 mg orally once daily.

Currently there is no evidence to support ASA for primary prevention in young patients (males < age 45, women < age 55) or patients over the age of 80 years. Men aged 45–79 years (for reduction of MIs) and women aged 55–79 years (for reduction of ischemic strokes) should take low-dose aspirin for primary prophylaxis if their potential benefit exceeds the risk of GI bleed. Aspirin 75–162 mg/day can be considered in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes who have a > 10% 10- year risk of developing coronary artery disease (CAD) based on Framingham risk score.

Commercially available products include the irreversible inhibitors ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and prasugrel and the reversible inhibitors cangrelor and ticagrelor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree