Chapter 21 Anomalous Origin of the Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Trunk

In 1886, St. John Brooks1 described two cases of “an abnormal coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery.” The diagnosis was subsequently called into question when the abnormal communication was attributed to a coronary arterial fistula. The seminal report of Bland, White, and Garland2 in 1933 referred to Maude Abbott’s case of a 60-year-old woman with anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk (Figure 21-1B). Bland, White, and Garland remain with us as eponyms.3 In 1962, Fontana and Edwards4 reported a series of 58 postmortem specimens.

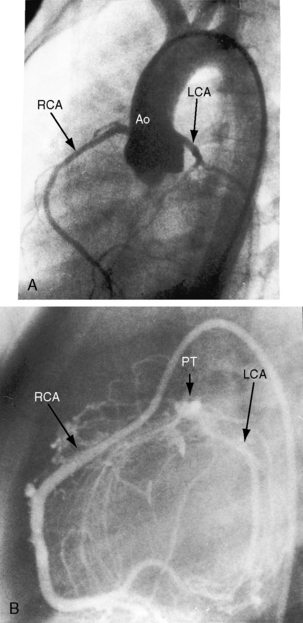

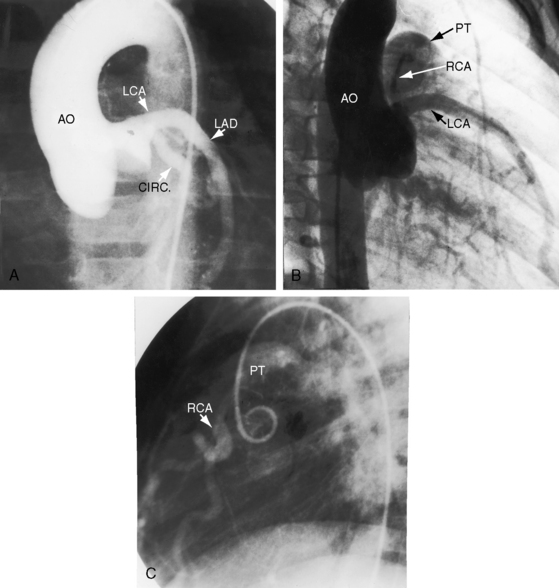

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk is the most common major congenital malformation of the coronary circulation, with an incidence rate estimated at 1 in 300,000 live births.5–8 More rarely, the right coronary artery (Figure 21-2), the left anterior descending coronary artery,9 the circumflex coronary artery,10–12 both coronary arteries,13–15 or a single coronary artery16 arises from the pulmonary trunk or its right or left branch.11,17 Stenosis of the ostium of the anomalous left coronary artery has been reported,18 and rarely, the anomalous artery courses within the aortic wall (intramural).19

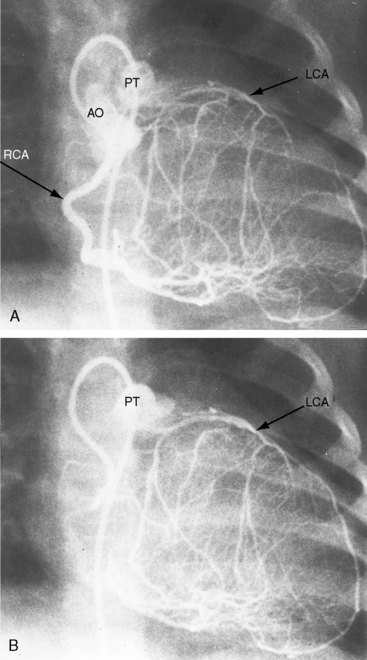

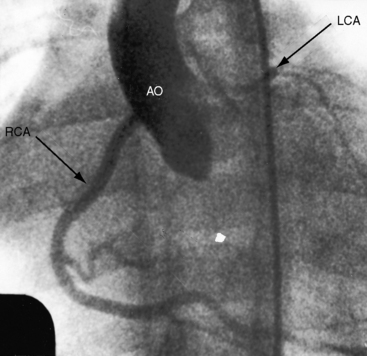

The anomalous left coronary artery is a thin-walled vessel that resembles a venous channel (Figures 21-1, 21-3, and 21-4).20,21 The right coronary artery originates from its normal aortic sinus, is dilated and tortuous (see Figures 21-1 and 21-4), and, on rare occasions, is aneurysmal.22 The portion of left ventricle perfused by the anomalous left coronary artery is thin, scarred, and dilated21 and occasionally forms a ventricular aneurysm. Conversely, the hypoperfused but viable portion of left ventricle increases its mass, often appreciably,20 because immature cardiomyocytes replicate in response to the hypoxemic stimulus.23 The left ventricular endocardium exhibits fibroelastosis and rarely is focally calcified. Interestingly, in adults with typical ischemic heart disease, newly formed elastic fibers appear within 3 or 4 weeks after a myocardial infarction and culminate in endocardial fibroelastosis in the vicinity of the infarct.24

Figure 21-3 Aortogram (anteroposterior projection) from a 4-year-old boy with anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk. A, The left coronary artery (LCA) originates from its aortic (AO) sinus and divides into the left anterior descending (LAD) and circumflex (CIRC) arteries. B, Intercoronary anastomoses visualize the left coronary artery (LCA) that originates from the pulmonary trunk as illustrated in Figure 21-5. C, Lateral projection shows the right coronary artery (RCA) entering the pulmonary trunk (PT).

Three theories have been proposed to explain the origin of a coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk.15 The first two theories are related to division of the embryologic truncus arteriosus.25 In the early embryo, two opposing truncal cushions enlarge and fuse to form the truncal septum, which divides the truncus arteriosus into aortic and pulmonary channels.25 Assuming that the coronary arteries originate as two endothelial buds (see Chapter 32), displacement of the origin of one or both of these buds could assign either or both coronary arteries to the portion of the truncus arteriosus destined to become the pulmonary artery. Alternatively, faulty division of the truncus could incorporate one or both coronary artery buds into the pulmonary artery. The higher incidence of anomalous origin of the left rather than the right coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk has been attributed to the proximity of the left aortic sinus to the truncal septum, so a relatively small displacement of the left coronary artery anlage suffices to cause the left coronary artery ostium to lie within the pulmonary artery.15 These theories presuppose that human coronary arteries originate as two endothelial buds that develop before or simultaneously with the division of the truncus arteriosus (see Chapter 32).15 Nor do these theories explain the presence of a third (accessory) coronary artery or anomalous origin of one branch of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk or explain why the relative sizes of the pulmonary artery, the aorta, and their valves are not altered by the proposed displacement of the truncal septum.15 The involution and persistence theory postulates that there are originally six coronary artery anlagen: three from the aorta, and three from the pulmonary artery (see Chapter 32).15 The coronary arteries that are destined to originate normally are believed to arise from two persistent anlagen in two separate aortic sinuses, whereas the anlage in the third aortic sinus, in addition to all three anlagen in the pulmonary sinuses, undergo involution.15 According to this theory, anomalous origin of one or both coronary arteries could result from persistence of pulmonary artery coronary anlagen together with involution of the normally persistent aortic coronary anlagen.15 In the presence of a bicuspid aortic valve, anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk is believed to be the expression of a single morphogenic defect.26,27 In the Syrian hamster, a relationship has been proposed between anomalous origin of the left coronary artery and the developmental morphology of the semilunar valves.26,27

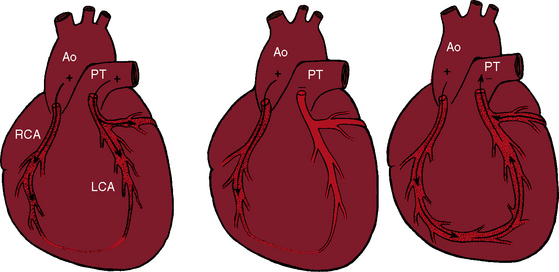

Myocardial ischemia is a serious sequela of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk.28 Ischemia does not stem from the fact that only one coronary artery originates from the aorta because the functional consequences of a congenitally single coronary artery are benign,29–31 with few exceptions (see Chapter 32).32,33 Nor is perfusion of the anomalous coronary artery by unoxygenated blood from the pulmonary trunk a satisfactory explanation because in cyanotic congenital heart disease the oxygen content of coronary arterial blood can be exceedingly low without producing myocardial ischemia. Why then does cardiac muscle become ischemic when the left coronary artery arises from the pulmonary trunk? The answer lies in the direction of blood flow through the coronary bed,34,35 as illustrated in the circulatory patterns of Figure 21-5. In fetal and early neonatal life, relatively high pulmonary arterial pressure results in antegrade blood flow into the anomalous left coronary artery (see Figure 21-5, first panel). The subsequent fall in pulmonary arterial pressure is accompanied by a parallel fall in blood flow into the anomalous left coronary (see Figure 21-5, middle panel). During this crucial transition, myocardial perfusion depends almost entirely on perfusion from the right coronary artery (see Figure 21-3).35,36 Myocardial ischemia is unavoidable unless adequate circulation from right to left coronary artery is established via intercoronary anastomoses, on which survival largely depends (see Figure 21-3B).21,35,37 Intercoronary anastomoses represent low-resistance pathways between the aorta and pulmonary trunk, in essence, arteriovenous fistulae,34 that have two opposing effects: (1) a desirable effect of reestablishing left coronary arterial perfusion; and (2) the undesirable effect of a coronary steal that bypasses the capillary bed and deprives the myocardium of oxygen.34,35,38 The idea of retrograde flow through an anomalous left coronary artery was originally proposed by 1886 by St. John Brooks:

“Here are two arteries belonging to the different circulations—the pulmonary and the systemic—anastomosing with each other. In these circulations, as is well known, the arterial pressure is very much greater in the systemic than in the pulmonary; how then did the blood flow in the anomalous coronary artery? There cannot be a doubt that it acted very much after the manner of a vein, and that blood flowed through it towards the pulmonary artery, and from thence into the lungs.”1

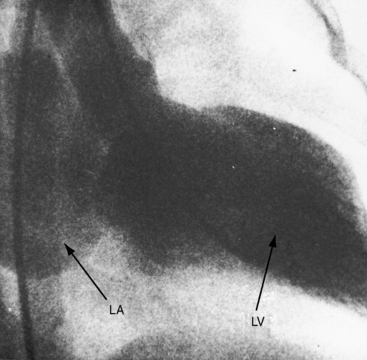

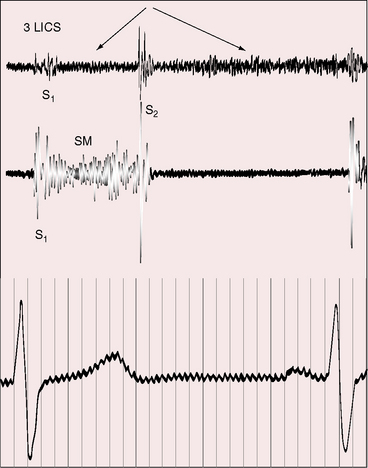

Physiologic, pathologic, and clinical derangements arise from the ischemic consequences of the transition from decreased antegrade perfusion of the anomalous left coronary artery, to flow from the right coronary artery through the low-resistance intercoronary anastomoses into the left coronary artery, followed by retrograde flow into the pulmonary trunk (see Figure 21-5). Ischemia causes the left ventricle to labor under three handicaps: first, viable myocardium is compromised, so contractility is depressed39; second, mitral regurgitation occurs as a consequence of ischemic papillary muscle dysfunction40 that adds to the hemodynamic burden (Figure 21-6); and third, flow via the intercoronary anastomoses constitutes a left-to-right shunt that is occasionally large enough to impose volume overload on the left ventricle.41 Although regional abnormalities of wall motion characterize anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk,42,43 infants tend to exhibit global hypokinesis.42,43

History

The outlook is most grave when both coronary arteries originate from the pulmonary trunk13–15 and is most favorable when the right coronary artery alone, or a left anterior descending or circumflex coronary artery alone, originates anomalously.10–12 The clinical course is a continuum that ranges from death in infancy to asymptomatic adult survival, with all gradations in between.35,44–47 Nevertheless, there are three general patterns: (1) serious symptoms in early infancy with death before 1 year of age; (2) early symptoms followed by gradual attenuation or disappearance; and (3) absence or virtual absence of early symptoms with asymptomatic survival to adulthood. Adult survival, even to age 90 years,48 has been reported and is much more likely with anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk, which, however, is not necessarily benign.

Eighty percent to 90% of patients with anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary trunk die in their first year.21,47 Presentation in the neonate is unusual because elevated pulmonary arterial pressure results in forward flow into the anomalous left coronary artery.49 Accordingly, infants appear healthy at birth and often remain so for about 2 months, after which symptoms usually begin.47 Irritability, dyspnea, wheezing, cough, diaphoresis, and ashen gray pallor are precipitated or aggravated by feeding, crying, or a bowel movement.47,50 Occasionally, the initial symptom is hoarseness thought to be caused by impingement of a dilated pulmonary artery on the recurrent laryngeal nerve.51 Chronic congestive heart failure is responsible for poor growth and development and is usually the cause of death. More than a third of patients presents with sudden cardiac death,52 in which case the diagnosis is necessarily post mortem. Symptomatic infants occasionally have improvement53 only to die suddenly during a relatively asymptomatic childhood or adolescence. One of the first known patients with the anomaly was the 60-year-old woman described by Maude Abbott54 in 1908. An elderly asymptomatic man played football in his youth and presented at age 67 years with sustained ventricular fibrillation.55 Angina may be delayed until the teens, or the anomaly may be discovered in asymptomatic children56 or adults because of mitral regurgitation (Figures 21-6 and 21-7). A 39-year-old mother of three presented with exertional fatigue.57 About 15% of individuals with anomalous origin of the left coronary artery survive to adulthood,58 some reaching the seventh or eighth decade.22,59 The malformation reveals itself in adults because of detection of the murmur of mitral regurgitation,22,59,60 because of a continuous murmur mistaken for a patent ductus (see Figure 21-7), or because of angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, cardiac arrest, or sudden cardiac death.34,45,46,61–64

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree