Postresuscitation electrocardiogram (ECG) in patients with aborted cardiac death may demonstrate ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), ST-T changes, intraventricular conduction delay, or other nonspecific findings. In the present study, we compared ECG to urgent coronary angiogram in 158 consecutive patients with STEMI and 54 patients not fulfilling criteria for STEMI admitted to our hospital from January 1, 2003 through December 31, 2008. At least 1 obstructive lesion was present in 97% of patients with STEMI and in 59% of patients without STEMI with ≥1 occlusion in 82% and 39%, respectively (p <0.001). Obstructive lesion was considered acute in 89% of patients with STEMI and in 24% of patients without STEMI (p <0.001). An acute lesion in STEMI had a higher thrombus score (2.6 vs 1.3, p = 0.05) and more often presented with Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction grade 0 to 1 flow (75% vs 36%, p <0.01). Percutaneous coronary intervention, which was attempted in 148 lesions in patients with STEMI and in 17 lesions in patients without STEMI, resulted in final Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction grade 3 flow in 87% and 71%, respectively (p = 0.34). In conclusion, STEMI on postresuscitation ECG is usually associated with the presence of an acute culprit lesion. However, in the absence of STEMI, an acute culprit lesion is still present in 1/4 of patients. An acute lesion in STEMI is more thrombotic and more often leads to complete occlusion. Urgent percutaneous coronary intervention is feasible and successful regardless of postresuscitation ECG.

Urgent coronary angiography after aborted sudden cardiac death has demonstrated evidence of coronary artery disease in >80% of patients and the presence of an acute thrombotic lesion in 38% to 48%. Early postresuscitation electrocardiogram (ECG), which is typically used to guide reperfusion strategy in acute coronary syndromes, may demonstrate ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or other abnormalities including ST-segment depression, T-wave changes, wide QRS complexes, intraventricular conduction delay, or different nonspecific changes. In the present study, we compared postresuscitation ECG to anatomic findings obtained by urgent coronary angiography. We were particularly interested in the relation between ECG and the presence of presumably acute culprit lesions amenable to urgent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Such information would be important for better selection of patients for urgent coronary angiography after successful resuscitation.

Methods

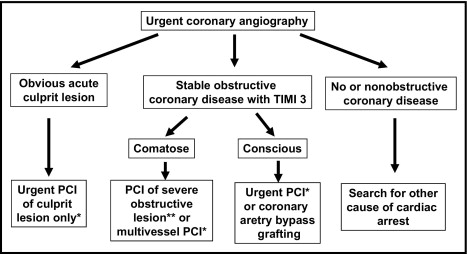

This retrospective study was performed at University Medical Center, Ljubljana and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Slovenian national ethics committee. Consecutive patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of presumed cardiac origin and re-establishment of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) in the field who underwent urgent coronary angiography from January 1, 2003 through December 31, 2008 were investigated. Decision for urgent coronary angiography was made by an acute cardiac care physician and an interventional cardiologist. Patients with an obvious nonischemic cause of cardiac arrest (i.e., documented nonischemic cardiomyopathy, electrolyte imbalances, Adam–Stokes syndrome) and with significant co-morbidities before cardiac arrest did not undergo urgent coronary angiography. This was the case also in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest without realistic hope for neurologic recovery. Unfavorable settings of cardiac arrest such as a nonwitnessed event, long delays to advanced life support with absence of bystander resuscitation, unshockable rhythm on the first ECG, and long interval to ROSC favored conservative management. We also excluded patients with previous coronary artery bypass grafting. The decision for urgent PCI was made by an interventional cardiologist according to our hospital guidelines ( Figure 1 ). In short, PCI was primarily performed for treatment of a presumed acute culprit lesion. After successful PCI of the acute lesion, PCI of other obstructive lesions was performed only for ongoing ischemia or hemodynamic instability. In the absence of a clear culprit, PCI of obstructive stenosis was performed if we believed the lesion might have contributed to cardiac arrest and if successful PCI would likely improve hemodynamic stability. Stenting, platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors, and intra-aortic balloon pump were used at the discretion of the interventional cardiologist. Mild induced hypothermia was used in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest as previously described. Postresuscitation 12-lead ECG, obtained after ROSC and before urgent coronary angiography, was reviewed by a single experienced cardiologist blinded to angiographic findings. Patients were divided into a STEMI group and a group not fulfilling criteria for STEMI. The latter group included patients with ischemic ST-T changes, bundle branch block/nonspecific intraventricular delay, nonspecific changes, and normal ECGs. Cardiac troponin I was measured on admission and after 12, 24, and 48 hours. Coronary angiograms were reviewed by experienced interventional cardiologists blinded to postresuscitation ECGs. Coronary lesions resulting in >50% decrease in luminal diameter were considered significant. Irregular eccentric coronary stenosis that might have a narrow neck, acute angles, or craters was judged to represent disrupted plaque or partially occlusive thrombus and was presumed the acute culprit lesion. Coronary flow was assessed by Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) classification. Coronary occlusion, defined as TIMI grade 0 to 1 flow, was considered acute or recent if there was angiographic evidence of thrombus at the site of occlusion or by the ability to pass a guidewire easily through the occluded segment. Collateral flow to the culprit vessel was estimated by Rentrop classification. TIMI thrombus grade scale from 0 (no angiographic evidence of thrombus) to 5 (total thrombotic occlusion) was used to estimate thrombus burden. Syntax score was calculated to estimate severity of coronary artery disease.

Numerical data are presented as mean ± SD or median and twenty-fifth to seventy-fifth percentiles. Unpaired 2-tailed t test and nonparametric Mann–Whitney test were used for comparisons between the STEMI and non-STEMI groups. Categorical data are presented as proportions. Fischer’s exact test and chi-square test were used for comparisons between groups. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

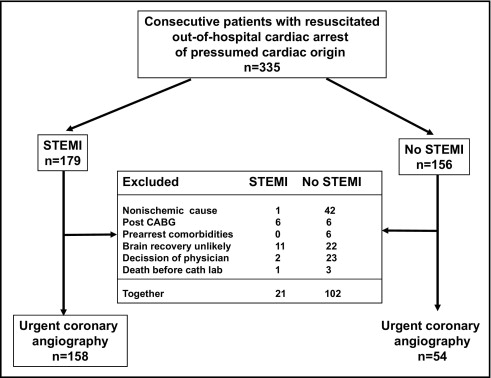

During the study period 335 consecutive patients who had been resuscitated after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest were admitted ( Figure 2 ). Because of exclusion criteria 158 of 179 patients with STEMI (88%) and 54 of 156 patients with non-STEMI (35%) underwent urgent coronary angiography. The 2 groups were comparable in general characteristics except for a greater incidence of previous coronary disease in patients without STEMI who had also a longer interval from collapse to advanced life support ( Table 1 ). Peak troponin I was significantly higher in the STEMI group (25.4 ± 31.1 vs 4.6 ± 7.7, p < 0.001).

| Variable | STEMI (n =158) | Non-STEMI (n = 54) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59 ± 13 | 60 ± 15 | 0.48 |

| Men | 134 (85%) | 46 (85%) | 1.00 |

| Hypertension | 78 (49%) | 33 (61%) | 0.19 |

| Diabetes | 29 (18%) | 7 (13%) | 0.39 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 61 (39%) | 16 (30%) | 0.38 |

| Current smoking | 62 (39%) | 15 (28%) | 0.21 |

| History of coronary event | 29 (18%) | 20 (37%) | 0.01 |

| Witnessed cardiac arrest | 146 (92%) | 45 (83%) | 0.07 |

| Basic life support | 63 (40%) | 19 (35%) | 0.62 |

| Collapse to advanced life support (minutes) | 5.5 ± 4.6 | 7.1 ± 4.9 | 0.04 |

| Shockable initial rhythm | 136 (86%) | 48 (89%) | 0.82 |

| Advanced life support to re-establishment of spontaneous circulation (minutes) | 15.1 ± 12.4 | 15.0 ± 11.5 | 0.96 |

| Comatose after re-establishment of spontaneous circulation | 126 (80%) | 45 (83%) | 0.69 |

| Hypothermia in comatose patients | 107/126 (85%) | 44/45 (98%) | 0.06 |

Most patients without STEMI demonstrated ischemic ST-T changes or bundle branch block ( Table 2 ). Obstructive coronary disease was present in 97% of patients with STEMI in whom most stenoses appeared to be acute. In the non-STEMI group obstructive coronary disease was documented in 59% with presumed acute lesions in 24%. At least 1 occlusion was present more often in patients with STEMI in whom occlusion was predominantly acute. Characteristics of presumed acute culprit lesions are listed in Table 3 . Because 2 patients with STEMI and 1 with non-STEMI each had 2 acute lesions, 142 and 14 lesions were analyzed. The left anterior descending coronary artery was the culprit artery in most regardless of ECG. Thrombus score was higher and TIMI grade 0 to 1 flow was present more often in patients with STEMI. Collateral flow to the infarct-related artery was better in patients with non-STEMI. PCI was attempted in 146 of 158 patients with STEMI (92%) in whom 148 lesions were treated. In the non-STEMI group PCI was performed in 17 of 54 patients (31%) in whom 17 lesions were treated (p <0.001). In the 2 groups PCI was directed mainly toward presumed culprit lesions ( Table 4 ). There was no significant difference in proportion of stenting, final TIMI flow, and use of intra-aortic balloon pump between groups.

| Variable | STEMI (n = 158) | Non-STEMI (n = 54) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postresuscitation electrocardiogram | <0.01 | ||

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 158 (100%) | 0 | |

| Ischemic ST-T changes | 0 | 21 (39%) | |

| Bundle branch block | 0 | 16 (30%) | |

| Nonspecific intraventricular delay | 0 | 5 (9%) | |

| Nonspecific changes | 0 | 2 (4%) | |

| Normal | 0 | 10 (18%) | |

| Cardiac arrest to angiography (minutes) | 120 (80–150) | 150 (105–255) | 0.08 |

| Presence of coronary artery disease | <0.01 | ||

| None | 3 (2%) | 22 (41%) | |

| Nonobstructive | 2 (1%) | 0 | |

| ≥1 stable obstructive lesion | 13 (8%) | 19 (35%) | |

| ≥1 presumed acute lesion | 140 (89%) | 13 (24%) | |

| Number of coronary arteries obstructed | 0.01 | ||

| 1 | 74 (47%) | 6 (11%) | |

| 2 | 42 (27%) | 11 (20%) | |

| 3 | 37 (23%) | 15 (28%) | |

| Unprotected left main coronary artery ≥50% | 8 (5%) | 3 (6%) | 1.00 |

| Presence of ≥1 occlusion | 129 (82%) | 21 (39%) | <0.01 |

| Presence of ≥1 acute occlusion | 108 (68%) | 4 (7%) | <0.01 |

| Presence of ≥1 long-term occlusion | 35 (22%) | 17 (31%) | 0.20 |

| Syntax score | 17.4 ± 8.6 | 16.3 ± 16.7 | 0.71 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree