Anatomy of the Thorax

Shari L. Meyerson

David A. Harpole Jr.

The bony and soft tissue components of the chest wall combine to create an anatomic space, which houses some of the most vital structures in the human body. The thoracic skeleton creates a protected space for the heart. It provides a protective framework for the lungs as well but also makes a significant functional contribution to respiration. This occurs through the interaction of the skeleton, chest wall musculature, and diaphragm. This chapter discusses the anatomic relationships of the bony and soft tissue components of the chest wall.

Surface Anatomy of the Thorax

The anterior chest wall has several significant landmarks. In all but the most obese subjects, the outline of the sternum can be visualized in the thoracic midline. Extending laterally and slightly upward from the suprasternal notch, the clavicles curve forward and then backward toward the shoulders. Especially in the thin patient, the lower margin of the rib cage can be seen to extend bilaterally from the inferior portion of the sternum at a downward angle, reaching its lowest level at the midaxillary line. The outline of the sternocleidomastoid muscles may be seen extending diagonally upward from the upper part of the anterior surface of the manubrium and the medial one third of the clavicle toward the base of the skull.

In men, the nipple lies near the lower border of the pectoralis major muscle, just lateral to the midclavicular line, over the fourth intercostal space or fourth or fifth rib. Nipple position is inconsistent in women because of the variable size of the mammary gland, which generally lies over the second to sixth ribs. The axillary tail extends upward into the axilla along the lower border of the pectoralis major muscle.

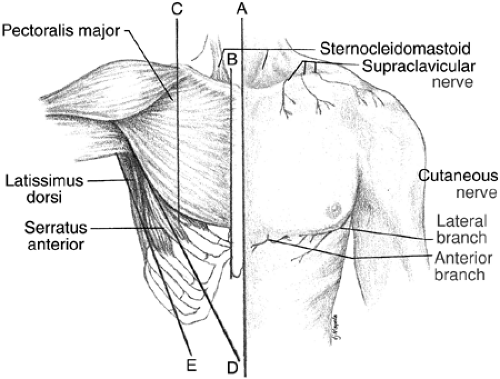

Several common lines of reference are used to describe positions on the chest wall. Many of these are shown in Figure 1-1. The midsternal line is a common point of reference and can be easily appreciated on almost all patients. The midclavicular line defines the midpoint of the anterior chest wall. The anterior axillary line describes a line extending caudally from the anterior border of the axilla. The midaxillary line defines the midpoint of the lateral aspect of the chest wall.

Cutaneous innervation of the anterolateral thoracic wall is supplied by supraclavicular nerves and terminal filaments of thoracic spinal nerves. Skin above, overlying, and slightly below the clavicle is supplied by supraclavicular nerves, which arise as terminal filaments of spinal nerves C3 and C4. The remainder of the thoracic wall is supplied by anterior cutaneous and lateral cutaneous branches of thoracic spinal nerves.

The posterior aspect of the thorax is covered almost completely by superficial muscles of the back, but a few bony landmarks are either visible or palpable. In the midline, the spinous process of the seventh cervical vertebra (vertebra prominens) stands out clearly. Below this process, the spine of the first thoracic vertebra may be equally visible. Spines of the remaining 11 thoracic vertebrae are less prominent superficially. They

extend downward so that the tip of each overlies the body of the vertebra below. In the midthoracic levels, the vertebral spines may be sufficiently long to overlie the intervertebral disc below the subjacent vertebra. The medial border of each scapula lies lateral to the midline at the level of the second to seventh ribs. The spine of the scapula extends diagonally upward from the medial border at about the third thoracic vertebra to end in the acromion at the shoulder.

extend downward so that the tip of each overlies the body of the vertebra below. In the midthoracic levels, the vertebral spines may be sufficiently long to overlie the intervertebral disc below the subjacent vertebra. The medial border of each scapula lies lateral to the midline at the level of the second to seventh ribs. The spine of the scapula extends diagonally upward from the medial border at about the third thoracic vertebra to end in the acromion at the shoulder.

Innervation of skin over the back is provided by medial cutaneous branches of dorsal rami of C4, C5, C8, T1, and T2 and by medial and lateral cutaneous branches of T3–T10. Considerable overlap and asymmetry of these nerves have been described by Johnston.5

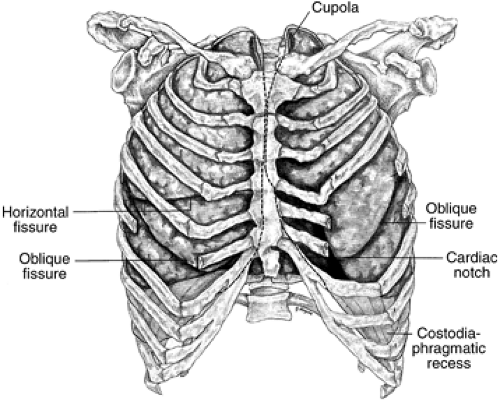

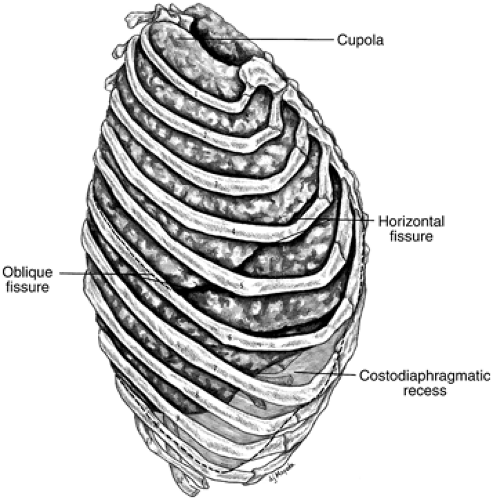

Knowledge of the surface relations of lobes and fissures of the lungs is important in percussion, auscultation, and radiographic evaluation of the pulmonary field. Although the lungs are in constant motion during respiration, the surface relations observed by Brock1 are shown in Figures 1-2 and 1-3. Knowledge of the topography of the various fissures of the lung is helpful in localizing abnormal pulmonary sounds as well as in localizing abnormal densities in radiographs of the chest.

Superficial Chest wall Musculature

The anterior aspect of the thorax is covered almost completely by the superficial muscles of the chest (Fig. 1-1). Immediately below the clavicle, the outline of the pectoralis major muscle is evident. These muscles originate from broad clavicular, sternal, and costal attachments that converge toward the axilla, forming a U-shaped tendon that attaches to the lateral lip of the intertubercular sulcus of the humerus. The lower margin of each pectoralis major muscle forms the anterior fold of the axilla. The pectoralis major muscles are supplied by medial and lateral pectoral nerves from the brachial plexus and are versatile in function. They adduct and rotate the arm medially and in addition may elevate it (clavicular portion) or depress it (sternocostal portion). If the shoulder girdle is held in fixed position, these muscles may also elevate the upper ribs in forced inspiration.

Deep to the pectoralis major muscles are the pectoralis minor muscles. They originate from slips on the second to fifth ribs and converge upward to a tendon that inserts on the coracoid process of the scapula. Supplied also by the medial and lateral pectoral nerves, these muscles are active in depressing and rotating the shoulders downward.

In thin, muscular subjects, the serratus anterior muscles can be visualized along the anterolateral aspects of the thoracic wall. They originate from slips on the upper eight ribs. They are applied closely to the thoracic wall as they pass upward and laterally to attach to the anterior surface and medial border of the scapula on either side. They hold the scapulae toward the thoracic wall and are important in adduction and elevation of the arms above

the horizontal position during scapulohumeral movement. On each side, the serratus anterior is supplied by the long thoracic nerve, which passes downward in the midaxillary line on the external surface of the muscle.

the horizontal position during scapulohumeral movement. On each side, the serratus anterior is supplied by the long thoracic nerve, which passes downward in the midaxillary line on the external surface of the muscle.

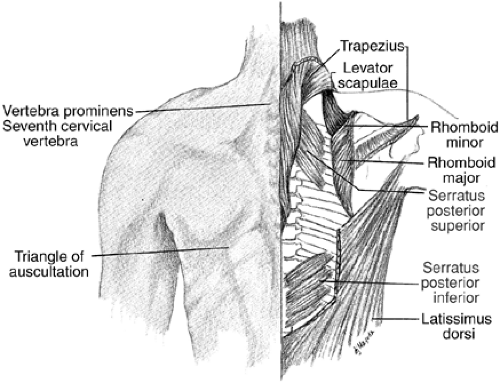

Figure 1-4. Surface features and superficial musculature of the posterior chest wall. The scapula has been displaced upward and laterally on the right side to permit a better view of the musculature. |

Surface contours of the back of the thorax are formed by muscles of the shoulder and scapular region; these muscles support and help move the upper extremity (Fig. 1-4). The posterolateral margins of the neck and uppermost limits of the shoulder are marked by the trapezius muscles. Each of these arises from broad origins, including the superior nuchal line of the occipital bone, the ligamentum nuchae of the neck, the spine of the seventh cervical vertebra, and spines and supraspinous ligaments of all thoracic vertebrae. Fibers sweep downward laterally and upward toward the shoulder, where they insert on the spine and acromion of the scapula and on the lateral one third of the clavicle. In lower cervical and upper thoracic levels, their aponeurotic origin is sufficiently devoid of muscle fibers to allow spines of thoracic vertebrae to be easily palpable. The trapezius muscles are supplied by spinal accessory nerves and filaments from cervical spinal levels C3 and C4. They are powerful stabilizers of the scapulae and shoulders and can elevate, depress, or adduct the scapulae, thereby aiding in the entire spectrum of scapulohumeral movements.

Lower and lateral parts of the back of the thorax are covered by the latissimus dorsi muscles. These muscles arise by broad aponeurotic origins from spines of lower thoracic vertebrae, the lumbodorsal fascia, and the iliac crests. Additional slips of muscle also arise from outer surfaces of the lower three or four ribs and blend with overlying components. Muscle fibers converge upward to insert by tendons into the intertubercular groove of the humerus on each side. In their upper thirds, these muscles converge with the teres major muscles to form the posterior folds of the axillae. The latissimus dorsi muscles are adductors, extensors, and medial rotators of the arm. Each is supplied by a thoracodorsal nerve from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. Because of attachment to the ribs, the latissimus dorsi muscles also can be considered accessory muscles of respiration.

The lower border of the trapezius muscle overlies the upper border of the latissimus dorsi. Near the point of overlap, a triangle is formed by the lateral border of the trapezius, the upper border of the latissimus dorsi, and the medial border of the scapula. Save for lower fibers of the rhomboid muscles, this area is free of an intervening mass of muscle tissue. Because a stethoscope placed over this triangle can detect respiratory sounds relatively free of distortion, it is called the triangle of auscultation.

Deep to the trapezius and latissimus dorsi muscles lies a layer of muscles involved in scapular movements and, to a lesser degree, movements of the ribs. Those related to the scapula are the levator scapulae, rhomboid major, and rhomboid minor muscles. The thin levator scapulae extend from the transverse processes of the first three or four cervical vertebrae diagonally downward to attach at the superior angle of the scapula on each side. The rhomboid minor may be fused with the rhomboid major. It extends from spines of the seventh cervical vertebra and first thoracic vertebra to the medial border of the scapula near the base of its spine. The rhomboid major arises from the spines of the second to fifth thoracic vertebrae and the supraspinous ligament between these vertebrae and is attached to the medial border of the scapula, usually below the spine of the scapula. The levator scapulae, rhomboid major, and rhomboid minor elevate, adduct, and retract the scapula. All are supplied by the dorsal scapular nerve, but the levator scapulae are supplied also by branches from C4 and C5.

The anatomy of the superficial chest wall muscles is extremely significant for the thoracic surgeon above and beyond their presence between the incision and the structures of interest within the thorax. The chest wall muscles can be of great aid in dealing with difficult problems both within and on the surface of the thorax. Muscle flaps can be utilized in the repair of a bronchopleural fistula to bring healthy, vascularized tissue into an infected field and promote closure. Muscles can also provide bulk to fill residual spaces within the chest. Commonly used muscles include the serratus anterior, which when based on the vascular pedicle, which runs along the lateral undersurface of the scapula, can be rotated into the chest. The serratus anterior provides a moderate amount of muscle bulk in most patients but, importantly, can usually easily reach a bronchopleural fistula originating from either a pneumonectomy or upper lobectomy stump. If more muscle bulk is required, as for an infected pneumonectomy space, the latissimus dorsi provides excellent bulk. It can also be harvested with an overlying skin paddle to fill full-thickness defects. Anterior spaces are often well filled with pectoralis major flaps. These can be rotated into the chest based on the major vascular pedicle, which runs on the underside of the muscle between it and the pectoralis minor. The pectoralis major also has a secondary blood supply consisting of the perforators from the internal mammary arteries at each of the intercostal spaces. The main vascular pedicle can be divided and the muscle flap based on the perforators, which allows a more extended range of motion including well across the midline for sternal defects.

Thoracic Skeleton

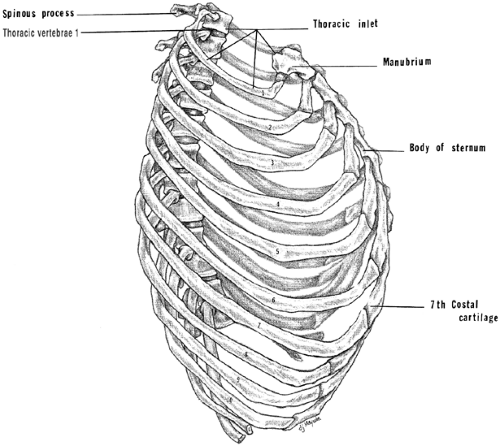

The thoracic skeleton consists of the sternum anteriorly, the vertebral column posteriorly, and 12 sets of ribs. The uppermost extent of the thoracic cavity is the thoracic inlet, which is a relatively small aperture containing major components of the vascular,

respiratory, and gastrointestinal systems in close proximity. The thoracic inlet is surrounded by the manubrium, the first ribs, and the first thoracic vertebra (Fig. 1-5). The anterior boundary is 2 or 3 cm below the posterior boundary. The thoracic inlet is roofed by the thickened endothoracic fascia (Sibson’s fascia), which covers the underlying parietal pleura bilaterally. Major structures passing through this region include the arterial supply and venous drainage of the head and upper extremities. These structures are joined by the trachea and esophagus, which pass from the neck into the thoracic cavity. The inferior border of the thoracic cavity is the much larger thoracic outlet. The outlet is bordered by the xiphoid process, fused costal cartilages of the 7th through 10th ribs, the anterior portions of the 11th ribs, the shafts of the 12th ribs, and the body of the 12th thoracic vertebra. The anterior margin of the outlet is at the level of the 10th thoracic vertebra. The lateral limits are at the level of the second lumbar vertebra as the ribs curve downward from their origins on the vertebral column, and the posterior margin is at the 12th thoracic vertebra. The outlet is therefore higher at its anterior margin than at its posterior limit and reaches its lowest level in the lateral aspect near the midaxillary line. The floor of the thoracic outlet is formed by the diaphragm, which is a mobile structure lying at different levels depending on the phase of respiration. Several important structures also traverse the thoracic outlet through openings in the diaphragm. These include the descending aorta, which passes through the diaphragm posteriorly, just to the left of the vertebral column and the esophagus, which passes through the esophageal hiatus just anterior and rightward of the aortic hiatus. On the right side the inferior vena cava passes though the diaphragm from its retrohepatic portion to enter the right atrium.

respiratory, and gastrointestinal systems in close proximity. The thoracic inlet is surrounded by the manubrium, the first ribs, and the first thoracic vertebra (Fig. 1-5). The anterior boundary is 2 or 3 cm below the posterior boundary. The thoracic inlet is roofed by the thickened endothoracic fascia (Sibson’s fascia), which covers the underlying parietal pleura bilaterally. Major structures passing through this region include the arterial supply and venous drainage of the head and upper extremities. These structures are joined by the trachea and esophagus, which pass from the neck into the thoracic cavity. The inferior border of the thoracic cavity is the much larger thoracic outlet. The outlet is bordered by the xiphoid process, fused costal cartilages of the 7th through 10th ribs, the anterior portions of the 11th ribs, the shafts of the 12th ribs, and the body of the 12th thoracic vertebra. The anterior margin of the outlet is at the level of the 10th thoracic vertebra. The lateral limits are at the level of the second lumbar vertebra as the ribs curve downward from their origins on the vertebral column, and the posterior margin is at the 12th thoracic vertebra. The outlet is therefore higher at its anterior margin than at its posterior limit and reaches its lowest level in the lateral aspect near the midaxillary line. The floor of the thoracic outlet is formed by the diaphragm, which is a mobile structure lying at different levels depending on the phase of respiration. Several important structures also traverse the thoracic outlet through openings in the diaphragm. These include the descending aorta, which passes through the diaphragm posteriorly, just to the left of the vertebral column and the esophagus, which passes through the esophageal hiatus just anterior and rightward of the aortic hiatus. On the right side the inferior vena cava passes though the diaphragm from its retrohepatic portion to enter the right atrium.

The sternum is an elongated, flat bone that lies in the anterior midline. It is 15 to 20 cm long and is formed from cartilaginous precursors that ossify separately to form three components: the manubrium, body, and xiphoid process (Fig. 1-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree