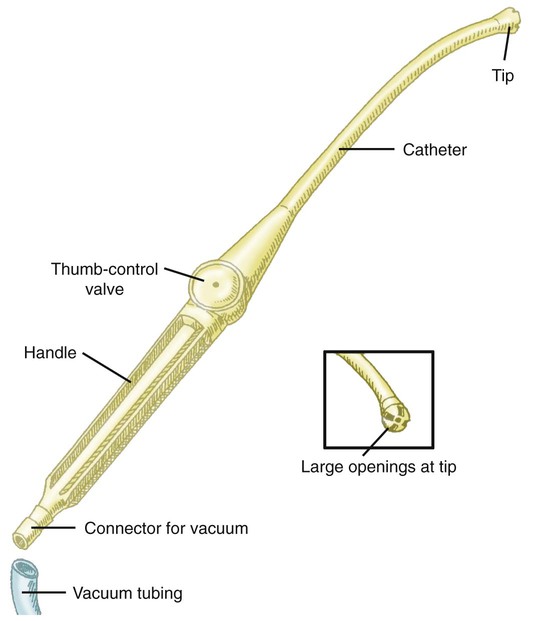

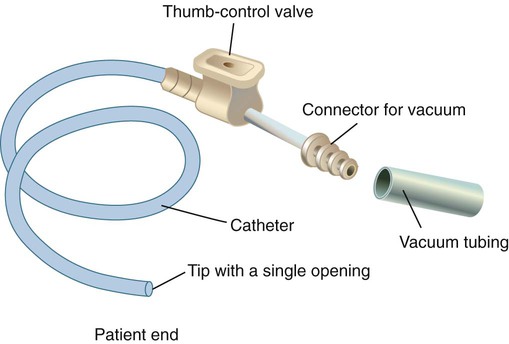

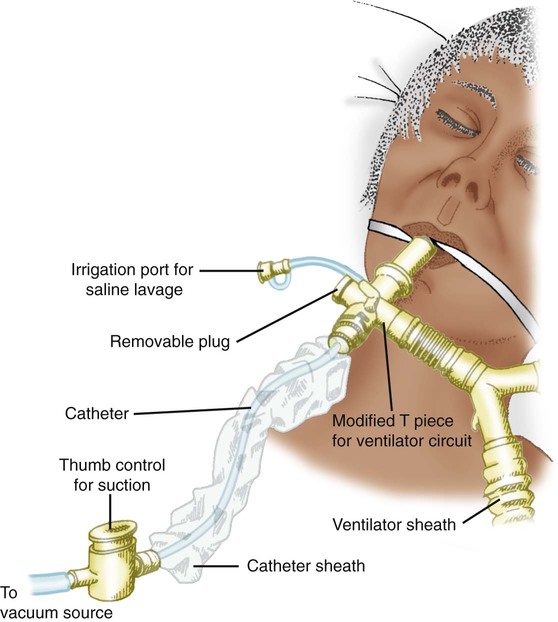

After reading this chapter you will be able to: Suction can be performed in either the upper airway (oropharynx) or the lower airway (trachea and bronchi). Secretions or fluids can also be removed from the oropharynx by using a rigid tonsillar, or Yankauer, suction tip (Figure 33-1). Access to the lower airway is via introduction of a flexible suction catheter (Figure 33-2) through the nose (nasotracheal suctioning) or artificial airway (endotracheal suctioning). Tracheal suctioning through the mouth should be avoided because it causes gagging. To guide practitioners in safe and effective application of this procedure, the American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC) has developed a clinical practice guideline on endotracheal suctioning of mechanically ventilated patients with artificial airways. Excerpts from the AARC guideline, including indications, contraindications, hazards and complications, assessment of need, assessment of outcome, and monitoring, appear in Clinical Practice Guideline 33-1.1 There are also two methods of suctioning based on how deep the suction catheter is inserted in the artificial airway: deep suctioning and shallow suctioning. Deep suctioning is when the catheter is inserted until resistance is met and then withdrawn approximately 1 cm before applying suction. Shallow suctioning is when the catheter is advanced to a predetermined depth, which is usually the length of the airway plus the adapter.2 Using shallow suctioning rather than deep suctioning is recommended in infants and children.3 Generally, a patient should never be suctioned according to a preset schedule. Although very thick secretions may not move with airflow and may not create any adventitious sounds, the patient should be assessed for clinical indicators, such as rhonchi heard on auscultation, which suggest the need for suctioning (see Clinical Practice Guideline 33-1). The equipment needed for endotracheal suctioning is listed in Box 33-1. The suction catheter, gloves, and cup are often prepackaged together in disposable sterile kits for use during the open suctioning technique. The AARC Clinical Practice Guideline suggests the closed suctioning technique to avoid disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, which interrupts ventilation and exposes the patient to infection risk. Suction pressure should always be checked by occluding the end of the suction tubing before attaching the suction catheter. The suction pressure should be set at the lowest effective level. Negative pressures of 80 to 100 mm Hg in neonates and less than 150 mm Hg in adults are generally recommended.4 Suction catheters are available in various designs, most with side ports to minimize mucosal damage. Most suction catheters for general purposes are 22 inches long (sufficient to reach the main stem bronchi) and sized in French units (external circumference). A curved-tip catheter, or catheter coudé, is available to help direct access to the left main stem bronchus. The size of the catheter may be more important than its design. A catheter that is too large can obstruct part or all of the airway by occupying too much of its opening. Too large a suction catheter combined with negative pressure quickly evacuates lung volume and can cause atelectasis and hypoxemia. To avoid this problem, the diameter of the catheter should be less than 50% of the internal diameter of the artificial airway in adults.5,6 In infants and small children, the diameter of the suction catheter should be less than 70% of the internal diameter of the artificial airway.7 An in-line suction catheter can be used for patients receiving ventilatory support (Figure 33-3). These systems are incorporated directly into the ventilator circuit and used repeatedly. Because this system allows suctioning without disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, it is recommended for suctioning patients who require high fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2) and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), who are at risk for lung derecruitment, and for neonates.8–10 In addition, cross contamination is less likely with such systems. The use of in-line suction catheters has been shown to be cost-effective because they need to be changed only if soiled or malfunctioning and not on a daily basis.11 However, in-line suction catheters have not been shown either to increase or to decrease the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.12 The extra weight an in-line catheter adds to a ventilator circuit may increase tension on the endotracheal tube, so care should be taken to support the ventilator tubing appropriately. Basic indications for the use of closed suction catheters are listed in Box 33-2.13 Routine instillation of sterile normal saline to aid secretion removal before suctioning is not recommended because there is insufficient evidence that this practice is beneficial, and it may increase infection risk (see Hazards and Complications in Clinical Practice Guideline 33-1). If the secretions are extremely tenacious, instillation of acetylcysteine or sodium bicarbonate (2%) may be more effective than normal saline; this generally requires a physician’s order. The use of these medications is discussed in more detail in Chapter 32. Before suctioning, delivery of 100% oxygen (O2) for 30 to 60 seconds to pediatric and adult patients is suggested, especially to patients who are at risk for hypoxemia. Also, the O2 concentration should be increased by 10% in neonates before suctioning14; this may be done by increasing the set FiO2 or activating the temporary 100% setting on microprocessor ventilators. Manual ventilation is not recommended because it is sometimes difficult to deliver 100% O2 this way.15 However, if there is no other alternative to hyperoxygenate the patient, PEEP should be maintained during the manual ventilation with 100% O2. Suction is applied while withdrawing the catheter. Total suction time should be kept to less than 15 seconds.16,17 After removing the catheter, it should be cleared using the sterile cup filled with sterile water or saline. The closed suction catheter has an adapter for saline vials to be placed in line with the device. The catheter is cleared by squeezing the saline vial and applying suction at the same time. Caution must be used to ensure saline is being drawn into the catheter and not down the airway. If any untoward response occurs during suctioning, the catheter should be immediately removed, and the patient should be oxygenated. Careful adherence to procedure is the best way to avoid or minimize complications of endotracheal suctioning. First, preoxygenation helps minimize the incidence of hypoxemia during suctioning. Also, it is recommended to preoxygenate and suction without disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, rather than disconnecting the patient and manually ventilating.18 A manual resuscitator cannot always provide 100% O2 or deliver a consistent tidal volume, and maintaining sterile technique and PEEP levels can be difficult. As previously described, use of the closed suction technique on ventilator patients can decrease the likelihood of hypoxemia, especially in neonates and adults requiring high FiO2 or PEEP, or both, or at risk for lung derecruitment. Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) has been reported during suctioning. These changes are transient, with values normally returning to baseline within 1 minute. However, in patients who already have an elevated ICP, these changes may be clinically significant. Should this problem occur, an aerosolized topical anesthetic given 15 minutes before suctioning may help reduce coughing and discomfort and any increase in ICP.19 The AARC has developed and published a clinical practice guideline on nasotracheal suctioning to guide practitioners in safe and effective application of this procedure. Excerpts from the AARC guideline, including indications, contraindications, hazards and complications, assessment of need, assessment of outcome, and monitoring, appear in Clinical Practice Guideline 33-2.20 The equipment and procedure for nasotracheal suctioning are similar to the equipment and procedure for endotracheal suctioning. Only the key differences are highlighted here. In addition to the equipment and supplies used for endotracheal suctioning (see Box 33-1

Airway Management

Describe how to perform endotracheal and nasotracheal suctioning safely.

Describe how to perform endotracheal and nasotracheal suctioning safely.

Describe how to obtain sputum samples properly.

Describe how to obtain sputum samples properly.

Assess the need for and select an artificial airway.

Assess the need for and select an artificial airway.

Identify the complications and hazards associated with insertion of artificial airways.

Identify the complications and hazards associated with insertion of artificial airways.

Describe how to perform orotracheal and nasotracheal intubation of an adult.

Describe how to perform orotracheal and nasotracheal intubation of an adult.

Assess and confirm proper endotracheal tube placement.

Assess and confirm proper endotracheal tube placement.

Describe the rationale and the methods for performing a tracheotomy.

Describe the rationale and the methods for performing a tracheotomy.

Identify the types of damage that artificial airways can cause.

Identify the types of damage that artificial airways can cause.

Describe how to maintain and troubleshoot artificial airways properly.

Describe how to maintain and troubleshoot artificial airways properly.

Describe techniques for measuring and adjusting tracheal tube cuff pressures.

Describe techniques for measuring and adjusting tracheal tube cuff pressures.

Identify when and how to extubate or decannulate a patient.

Identify when and how to extubate or decannulate a patient.

Describe how to use alternative airway devices.

Describe how to use alternative airway devices.

Describe how to assist a physician in setting up and performing bronchoscopy.

Describe how to assist a physician in setting up and performing bronchoscopy.

Suctioning

Endotracheal Suctioning

Clinical Practice Guideline

Equipment and Procedure

Step 1: Assess Patient for Indications

Step 2: Assemble and Check Equipment

Step 3: Hyperoxygenate Patient

Step 5: Apply Suction and Clear Catheter

Minimizing Complications and Adverse Responses

Nasotracheal Suctioning

Clinical Practice Guideline

Equipment and Procedure

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Airway Management