Acute Type B Dissection without Malperfusion

AMANI D. POLITANO and GILBERT R. UPCHURCH Jr

Presentation

A 51-year-old female presented to the emergency department with several days of chest pain that she describes as sharp and stabbing. Her past medical history is remarkable for hypertension for which she is on hydrochlorothiazide. She is a current 1-pack-per-day smoker with a 30-pack-year history. On examination, her vital signs are significant for a blood pressure of 170/74 mm Hg, a heart rate of 91 beats per minute, and moderate anxiety. Her physical examination demonstrates a nontender abdomen and equal bilateral radial, femoral, and distal pulses. She has well-healed scars from a prior cholecystectomy. She is retired, volunteers locally, and walks 3 days a week.

Differential Diagnosis

The acute onset of back pain can have several etiologies, including musculoskeletal, cardiac, vascular, or gastrointestinal. Characteristics of the presentation should help to guide further evaluation and workup. Acute life-threatening conditions include myocardial infarction and aortic dissection or aneurysm rupture, and therefore, these entities should be evaluated promptly. Further history of genetic disorders (Marfan, Ehlers-Danlos, and Loeys-Dietz syndromes) or inflammatory syndromes may also aid with diagnosis and help to predict which patients are predisposed to an increased risk of dissection.

Case Scenario

Further inquiry reveals no history of reflux or peptic ulcer disease. The patient denies any prior similar pains or history of angina. As she has already had a cholecystectomy and does not drink, the likelihood of pancreatitis, which can also cause back pain, is low. However, it is worth evaluating these scenarios, as well as aortic pathology, since they can present without prodrome.

Workup

An electrocardiogram and laboratory assessment including complete blood count, chemistry panel, amylase, lipase, and troponin should be obtained. An intravenous contrasted cross-sectional imaging study in arterial phase, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging, is obtained. Additionally, evaluation of delayed contrast phases can elicit evidence of venous pathology or delayed renal or gut perfusion. Even in the absence of clinical signs of malperfusion, careful evaluation of the appearance of splanchnic vessels on imaging can indicate involvement that may be more concerning for impending malperfusion and warrant more aggressive therapy.

Case Scenario

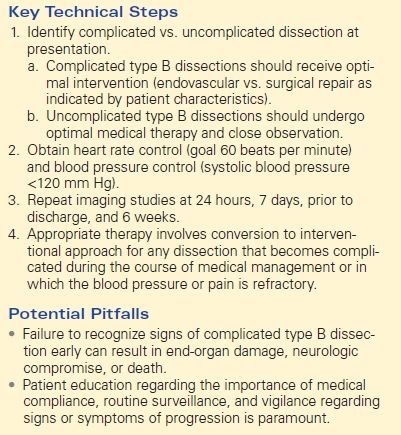

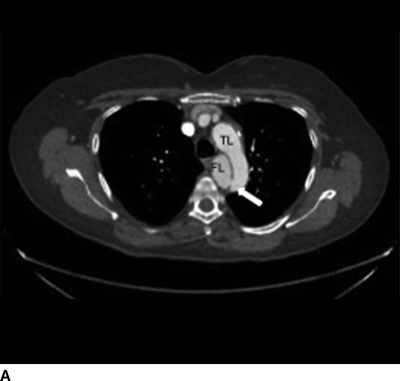

The patient demonstrated normal values for all of the above and an electrocardiogram (EKG) documented sinus tachycardia. A CT scan demonstrates a type B aortic dissection just distal to the ligamentum arteriosum (Fig. 1). The dissection continues through the thoracic and abdominal aorta and terminates within the right common iliac artery. The celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, and bilateral renal arteries arise from the true lumen (Fig. 2). There is no mesenteric thickening to suggest ischemia. An accessory right renal artery arises from the false lumen. The inferior mesenteric artery is also patent. Multiple fenestrations are present in the thoracic aorta. Delayed imaging demonstrates appropriate contrast filling of the renal collecting system and bladder. The maximal aortic diameter is 4.0 cm.

FIGURE 1 Aortic dissection originating distal to left subclavian artery, demonstrating true lumen (TL), false lumen (FL), and fenestration (arrow, A). Longitudinal view demonstrates proximal fenestration (arrow) and extent of dissection into right common iliac artery (B).

FIGURE 2 Sagittal images demonstrating distal fenestration (single arrow, A). Celiac and superior mesenteric arteries (double arrow, A) and right renal artery (B) originate from the true lumen.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Aortic dissections remain the most common vascular injury with potentially catastrophic consequences. The incidence is difficult to capture due to immediately fatal cases, but ranges from 2.5 to 30 cases per million persons per year. The presentation can be defined as hyperacute (less than 24 hours), acute (24 hours to 2 weeks), subacute (2 to 6 weeks), or chronic (greater than 6 weeks). The pathophysiology involves a disruption of the intima and subsequent separation of the intima and media by tracking blood into a dissection plane. Further anatomic definition is traditionally reported as either the DeBakey (type I-IIIa/b) or Stanford (type A/B) classification systems. In either case, dissections that involve the ascending aorta are considered surgical emergencies and warrant rapid intervention.

Acute type B aortic dissection presents most commonly with the sudden onset of back, chest, or abdominal pain, or a combination thereof. Abdominal pain or peripheral numbness in the absence of chest or back pain is indicative of end-organ pathology. Absence of distal pulses is also quite concerning and can be confused with other etiologies, such as embolic or thrombotic events.

Acute type B dissections can be designated uncomplicated or complicated based on evidence of malperfusion, size greater than 5.5 cm maximal diameter, annual increase in size by 4 mm, or aortic rupture. Patients with otherwise uncomplicated features of their dissection who cannot obtain blood pressure control on three or more agents should be considered refractory to medical management and treated as a complicated dissection. Conversely, presentation associated with hypotension (systolic blood pressures less than 90 mm Hg) is concerning for rupture, malperfusion, cardiac involvement, or intra-abdominal catastrophe and should also be treated aggressively.

Initial therapy should begin with admission to the hospital, strict blood pressure control via intravenous medications, and careful monitoring, including an arterial line. Heart rate control with the use of beta-blockade or calcium channel blockers should precede any vasodilitory agents to avoid reflex tachycardia, which can increase stress on the aortic wall. If this is insufficient to reduce systolic blood pressure below a target of at least 120 mm Hg, addition of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and vasodilatory medications should be employed. Serial laboratory examinations to evaluate renal function and bowel perfusion should be followed. If there are any signs of malperfusion in the early presentation, conversion to endovascular or operative intervention should be pursued.

Case Continued

The patient is admitted, and with the aid of intravenous esmolol and nicardipine infusions, her heart rate decreases to near 60 beats per minute and her blood pressure remains under 120 mm Hg systolic. Her CT scan is repeated at 24 hours with no change in the aortic diameter and no extension of the dissection. Serial laboratory values demonstrate stable creatinine, amylase and lipase, and lactic acid. Her physical examination, particularly the abdominal and distal pulse exams, remains stable and uncompromised. She is then transitioned to oral medications to maintain the goal parameters.

Discussion

Studies have shown that beta-blockade is associated with improved survival for all patients with aortic dissections, and calcium channel blockers are associated with improved survival in patients with type B dissections treated with best medical management (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Acute Type B Dissection without Malperfusion