Acute Limb Ischemia after Open AAA Repair

T. KONRAD RAJAB and MATTHEW T. MENARD

Presentation

A 75-year-old obese male presents to the emergency department with the acute onset of abdominal pain. He is a smoker with a known abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). The patient collapses on the way from the triage area to his assigned stretcher and requires cardiopulmonary resuscitation for approximately 20 minutes. Following return of spontaneous circulation, a computed tomographic angiogram (CTA) is performed and demonstrates a ruptured AAA. The aneurysm extends into both common iliac arteries and is felt not to be suitable for endovascular stent grafting given the absence of a suitable proximal landing zone. The patient is taken emergently to the operating room, where laparotomy reveals a small amount of free peritoneal blood. The decision is made not to administer heparin prior to supraceliac cross-clamping. The aneurysm is repaired using an aortobifemoral graft with 10-minute supraceliac and 30-minute infrarenal clamp times. Following construction of the distal anastomoses, the patient is hemodynamically stable with systolic blood pressure of 104 mm Hg on a 5 mcg/min Levophed infusion. On inspection of the lower extremities, however, the left foot is noted to be pale and cooler than the left. Femoral pulses are palpable bilaterally. The patient had faintly dopplerable pedal signals bilaterally prior to induction, and currently, there are strongly biphasic right pedal Doppler signals. The left popliteal and pedal pulses and Doppler signals are absent.

Differential Diagnosis

The incidence of acute limb ischemia after open AAA repair is approximately 5%. The differential diagnosis depends on whether one or both legs are affected. Acute ischemia affecting both legs can be caused by a technical issue with the proximal anastomosis, thrombus formation within the aortic tube graft or within the main body of a bifurcated graft, distal thromboembolism to both graft limbs or lower extremities, atheroembolism, or systemic hypotension.

Acute limb ischemia affecting just one leg only usually results from a technical problem with the distal anastomosis, thromboembolism, atheroembolism, or in situ thrombosis of the ipsilateral graft limb. One generally has a suspicion as to which among these diagnostic possibilities is most likely given the intraoperative conduct of the procedure.

Workup

While thromboembolism is the most frequent cause for acute limb ischemia after AAA, this patient also has risk factors for technical complications at the anastomoses, in situ thrombosis, and hypotension. Technical complications are more likely during urgent and emergent cases when expedient operative conduct is necessary, and a less-than-perfect technical result may be accepted in interest of shortening operative time. Additionally, standard heparinization dosing is often modified in the setting of a ruptured aneurysm or actively bleeding patient, raising the risk of in situ thrombosis. High blood loss also puts the patient at risk for systemic hypotension and further increases the risk of graft or outflow thrombosis.

Evaluation should begin by evaluating the patient’s hemodynamic status. Hypotensive patients are aggressively resuscitated. Next follows a full vascular examination of the lower extremities, focused on assessment of the peripheral pulses and Doppler signals. Hematomas at the operative site should raise concern for a technical complication at the anastomosis and possible graft compression. In the event of acute limb ischemia, platelet counts should be checked to rule out heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and creatinine kinase should be monitored given the risk of ischemia-induced rhabdomyolysis.

Diagnosis and Treatment

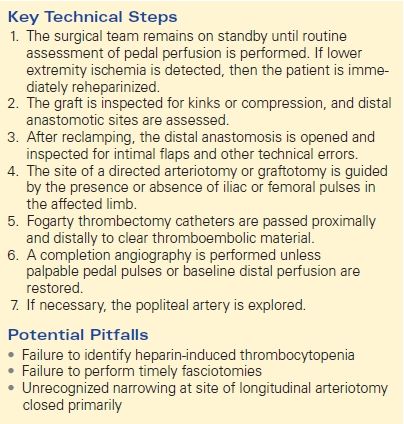

The diagnosis of acute limb ischemia after AAA repair is usually made relatively easily by routine postoperative physical examination. This is best done while the surgical team remains scrubbed, to allow for immediate treatment of any identified problem (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Acute Limb Ischemia after Open AAA Repair

As mentioned, the most common etiology of acute limb ischemia following AAA repair is either embolism of disrupted plaque or chronic thrombus or new thrombus formation. In a study of 100 consecutive patients undergoing open AAA repair, 6 out of 7 patients who developed acute limb ischemia had sustained distal embolization of thrombus and debris. Atheroembolization is frequently caused during clamping, and as such, this risk can be reduced by careful assessment of all potential clamp sites prior to clamp placement. This should entail both a thorough review of all possible clamp sites on any available preoperative CT imaging and intraoperative palpation. Thrombus formation can also occur during the period of diminished limb perfusion when the arterial clamps are in place, with subsequent embolization following clamp release. This can potentially be avoided by adequate anticoagulation during clamping, frequent flushing during construction of the anastomoses, adequate forward and back bleeding during final flushing maneuvers, and efforts to minimize clamp times. Appropriate monitoring of the activated clotting time can be of particular help in gauging the degree to which ongoing prophylactic heparinization is successful. Attention to detail in constructing the anastomosis, with particular focus on removing or tacking any areas of disrupted intima, is a further important safeguard. The factors that raise suspicion for a thromboembolic etiology in the patient discussed above are the unilateral leg involvement and the reduced level of heparin utilized prior to cross-clamping.

Formal angiography can be used to confirm suspected acute limb ischemia and also to help in determining the etiology. Ideally, this is performed expeditiously in the operative suite using the fixed imaging of a hybrid operating room or a portable C-arm.

Once acute limb ischemia is diagnosed, the patient is immediately reheparinized to prevent further propagation of occlusive thrombus, and preparations are made for emergent surgical reintervention.

Surgical Approach

Maintaining a sterile field, sterile instruments, and a scrubbed surgical team until adequate distal perfusion is confirmed is standard practice after open aortic surgery and will serve to minimize any delay until necessary reintervention can be performed. Physical examination findings dictate the strategic approach to the reintervention.

Following exploration of the wound, any obvious technical problems, such as kinking of the graft or compression of a graft limb by the inguinal ligament, are addressed. If there is an absent pulse in either the proximal native common iliac artery (in the event of initial reconstruction with a tube graft) or the proximal limb of a bifurcated graft, one may elect to reapply clamps and perform a unilateral limb graftotomy or iliac arteriotomy. This may result in identification of a focal raised intimal flap or thromboembolic plug, lending itself to a relatively easy surgical fix.

Alternatively, one can initially utilize a common femoral artery approach, particularly if the common femoral artery was already dissected during an aortobifemoral reconstruction or in the setting of a palpable femoral pulse in the ischemic limb. Depending on the degree of suspicion of the underlying cause, either a transverse or longitudinal graftotomy or arteriotomy can be carried out, or the entire distal anastomosis can be taken down. Any technical errors are corrected, and the intima is carefully inspected. Simply tacking down an intimal plaque may be sufficient, or performing a more extensive endarterectomy may be required. Once technical problems with the anastomosis are excluded, the antegrade flow is evaluated by releasing the proximal clamp. Fogarty catheters are passed retrograde to remove any proximal thrombus; typically, a 4- or 5-French Fogarty balloon will be used for a graft limb or the native iliac artery. A 3-French Fogarty balloon is also passed distally to clear any thrombus or embolic debris from the profunda femoral and superficial femoral arteries as well. At this point, the femoral access is closed and distal perfusion assessed. If insufficient, further angiography may be undertaken to identify the location of any remaining distal thrombotic material, or a below-knee popliteal exploration can be carried out. Extending the dissection to expose the origins of each of the tibial vessels and performing a longitudinal arteriotomy rather than a transverse arteriotomy allow directed passage of a 2-French Fogarty balloon into each of the tibial runoff vessels. A longitudinal incision typically mandates patch angioplasty to avoid stenosis. After adequate backflow is obtained, the arteriotomies are closed. Attention is paid to the order of removal of the clamps during closure of the arteriotomy. Attention should be given to adequate flushing of both the inflow and the outflow vessels prior to completing the arteriotomy closure by transiently releasing the proximal and distal clamps; detection of any fresh thrombus during this step would typically indicate an insufficient level of heparinization. Finally, the distal perfusion should be reassessed to confirm adequate restoration of flow to the ischemic limb. A completion angiogram is recommended at this point to ensure that the thrombectomy was technically successful. While it is appropriate in certain circumstances to defer on further treatment of a small amount of residual thrombus that does not appear to be causing hemodynamic compromise, it is important to be aware that remnant thrombus may serve as a nidus for subsequent recurrent thrombotic complications.

In instances when extraction of in situ thrombus or emboli proves prohibitive, a definitive salvage bypass procedure around the obstruction may prove necessary. This will typically be in the setting of chronic multilevel atherosclerotic occlusive disease, in patients in whom important collaterals have been affected by the acute process or in whom the profunda femoral artery proves insufficient to sustain ongoing patency of the inflow graft. While any such infrainguinal graft is ideally performed with saphenous vein, the importance of timely restoration of distal perfusion may render a prosthetic conduit the better choice. Similarly, if efforts at the iliac or femoral level fail to reestablish adequate aortoiliac inflow, an expeditious femorofemoral bypass is usually the most appropriate bailout maneuver. Alternatively, intraoperative endovascular balloon angioplasty or stent placement is an acceptable and potentially time-saving salvage option. If the ischemic time is relatively short, then lower extremity fasciotomies are not necessary. However, close postoperative observation with serial neurovascular examinations and compartment checks are mandatory in the event they are deferred.

Special Intraoperative Considerations

While a rare event in the current era, falling platelet counts and the presence of white-colored thrombus formation in the operative field should raise suspicion for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. If identified, intravenous heparin should be discontinued and substituted with bivalirudin or an equivalent alternative. Any heparin- coated central lines should also be replaced.

Postoperative Management

The risk of compartment syndrome following acute limb ischemia after AAA repair obligates serial neurovascular examination for evidence of developing ischemia and close monitoring for rhabdomyolysis. Additional postoperative management efforts include appropriate wound care and the maintenance of ongoing anticoagulation. Open fasciotomy wounds can be managed by vacuum sponge dressings until subsequent secondary operative closure, eventual outpatient resolution or split thickness skin grafting. If no technical complication explaining the thrombosis is found, the patient should be considered for evaluation of a hypercoagulable disorder.

TAKE HOME POINTS

- Lower extremity ischemia is an early complication of open AAA repair.

- Maintaining an adequate level of systemic anticoagulation, performing antegrade and retrograde flushing maneuvers and noting appropriate forward and back bleeding prior to completing the distal anastomoses, and vigilant attention to tacking areas of disrupted intima to avoid intimal flaps are all critical steps in preventing acute limb ischemia during AAA repair.

- Diagnosis is most frequently made by physical examination. Peripheral pulses are checked after completion of the distal anastomosis while the surgical team remains on standby.

- Treatment of lower extremity ischemia after open AAA repair involves immediate reheparinization and surgical exploration.

- Postoperatively, patients require serial pulse exams and compartment checks.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Ameli FM, Provan JL, Williamson C, et al. Etiology and management of aortofemoral bypass graft failure. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;28:695–700

Cronenwett JL, Johnston KW, Rutherford RB. Rutherford’s Vascular Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2010:1966.

Hirsch AT, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2006;113(11):e463–e654.

Imparato AM. Abdominal aortic surgery: prevention of lower limb ischemia. Surgery. 1983;93:112–116.

Imparato AM, Berman IR, Bracco A, et al. Avoidance of shock and peripheral embolism during surgery of the abdominal aorta. Surgery. 1973;73:68–73.

Jang IK, Hursting MJ. When heparins promote thrombosis: review of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Circulation. 2005;111(20):2671–2683.

Starr DS, Lawrie GM, Morris GC Jr. Prevention of distal embolism during arterial reconstruction. Am J Surg. 1979;138: 764–769.

Tchirkow G, Beven EG. Leg ischemia following surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Surg. 1978;188:166–170.

Towne JB, Bernhard VM, Hussey C, et al. Antithrombin deficiency: a cause of unexplained thrombosis in vascular surgery. Surgery. 1981;89:735–742.

CLINICAL SCENARIO CASE QUESTIONS

1. Acute limb ischemia after open AAA repair is most frequently diagnosed by:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree