Chapter 161

Acute Ischemia

Evaluation and Decision Making

Jonothan J. Earnshaw

Acute ischemia of the limb represents one of the toughest challenges encountered by vascular specialists. The diagnosis and initial assessment are largely clinical, and diagnostic errors can result in a high price to the patient—amputation or even death. Amputation and death rates remain high despite intervention, which is in contrast to major advances in the treatment of many other vascular diseases. Acute ischemia is often an end-of-life condition that presents in a patient with multiple medical comorbidities. Therefore careful clinical assessment of the individual is as important as assessment of the limb. Unlike many other vascular conditions, there is no one definitive treatment; a variety of modalities are available, including anticoagulation, operative intervention, thrombolysis, and mechanical thrombectomy. Selection of the most appropriate intervention or combination of interventions can be critical to the eventual outcome.

Etiology and Pathology

Acute ischemia is the result of a sudden deterioration in the arterial supply to the limb. Excluding trauma and iatrogenic causes, there are two main reasons for acute ischemia to occur: arterial embolism and thrombosis. The distinction between thrombosis and embolism is important in terms of diagnosis and prognosis, but it may not be crucial when deciding on the form of treatment.

Embolism

Embolism (from the Greek embolos, or “plug”) is the result of material passing through the arterial tree and obstructing a peripheral artery. Usually the source of the embolus is the heart, and the material is mural thrombus that has accumulated and detached. The other main cause is atherosclerotic debris from a diseased proximal artery, often the thoracic aorta, in individuals with a heavy burden of atherosclerotic disease.

Once the embolus detaches, it passes easily through large arteries and lodges peripherally, usually at an arterial bifurcation, where vessels naturally narrow. Emboli can occlude any artery, but in the legs, the common femoral and popliteal arteries are commonly obstructed. Only large emboli, so-called saddle emboli, occlude the normal aortic bifurcation. In the upper extremity, the brachial artery bifurcation and the brachial artery at the takeoff of the profunda brachialis artery are frequent locations for emboli to stop.

Embolic ischemia is usually catastrophic because it often occurs in otherwise normal arteries, without any established collaterals. Typically, the patient presents with an acute white leg, including a complete neurosensory deficit. Embolic occlusion is also progressive; the ischemia worsens as secondary thrombus forms both proximal and distal to the occlusion. The secondary thrombus is the plum-colored clot removed at embolectomy (Fig. 161-1). It is particularly important that this secondary thrombus be removed because it may be responsible for obstruction in smaller distal vessels. If the presentation is delayed, the secondary thrombus adheres to the arterial wall, making it particularly resistant to removal with an embolectomy catheter and less easily lysed by thrombolytics.

Cardiac Embolism

Atrial and Ventricular.

Embolism may occur in patients with otherwise normal arteries, with the embolic material usually arising from the heart. Embolic material from the heart usually consists of platelet-rich thrombus. Often it is organized, giving it the characteristic white surface on removal at embolectomy. The most common cause is atrial fibrillation; thrombus forms in the left atrial appendage as a result of stasis due to incoordinate contractions of the atrium and ventricle.

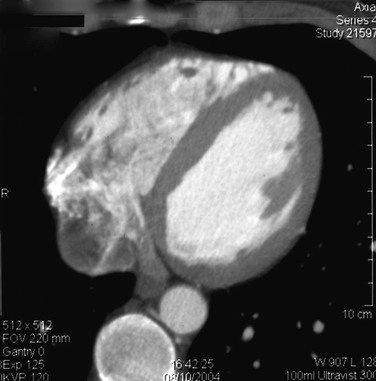

Mural thrombus, as a result of acute myocardial injury due to infarction, is a particularly dangerous cause of embolism. The patient has not only an ischemic extremity but also a high-risk medical condition (Fig. 161-2). Left ventricular aneurysm is also a high-risk cause of embolism because these patients have a low cardiac output as a result of the previous infarcts that caused the aneurysm.

Figure 161-2 Computed tomogram of the heart showing mural thrombus that caused brachial embolus (same patient as in Fig. 161-9).

In the past, cardiac valve disease was the main cause of arterial embolism, but advances in the management of these patients have virtually eliminated this as a cause.1–3 Instead, many patients now have artificial heart valves, and those with prosthetic valves are usually anticoagulated. Embolism is rare in patients with porcine replacement heart valves.

Paradoxical.

Paradoxical embolism occurs when a clot from the venous system, usually a deep venous thrombosis, travels through a patent foramen ovale into the arterial system. The clinical clue is acute arterial ischemia in a young patient with known deep venous thrombosis.4

Endocarditis.

Bacterial endocarditis is an infrequent diagnosis since the introduction of widespread echocardiography and antibiotics. However, certain patient groups are at risk, including intravenous drug users, patients with indwelling arterial or venous lines, and those who are immunocompromised.

Cardiac Tumor.

Atrial myxoma is a benign tumor of the left atrium that may fragment as it enlarges. Surgeons are advised to send the embolic material for histology if there is anything atypical about the material removed at embolectomy or if the patient is young with no obvious reason for embolic disease.5

Noncardiac Embolism

Atheroembolism.

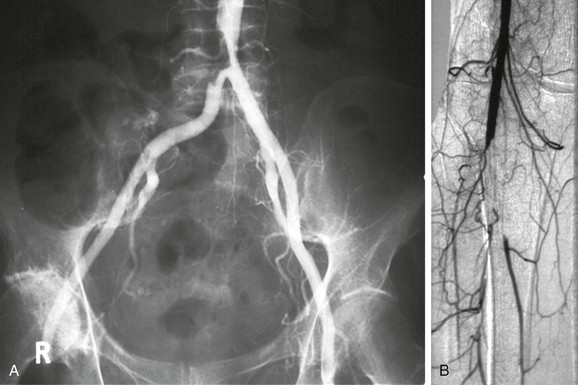

Another source of embolism is the native arteries themselves. Particularly in patients with extensive atherosclerotic disease in major arteries such as the aortic arch or the descending thoracic aorta, fragments of plaque or adherent thrombus may detach and cause symptoms that mimic cardiac embolism (Fig. 161-3). The embolic material may consist entirely of platelet-rich thrombus, similar to embolism. More sinister are fragments of atheromatous plaque that detach (Fig. 161-4); these are more difficult to remove at embolectomy and may irreversibly occlude small distal vessels (see Chapter 164). Atheroembolism may occur spontaneously or may be precipitated by intra-arterial manipulation of wires or catheters during cardiac or peripheral arterial interventions.

Aortic Mural Thrombi.

Occasionally, patients with hypercoagulable conditions develop an aortic mural thrombus in the absence of aortic pathology, which then embolizes to a limb. This should be suspected in a patient without atherosclerotic vascular disease and in whom the cardiac evaluation is negative. Although the acutely ischemic limb may need urgent treatment, the underlying aortic pathology can often be treated simply by anticoagulation, with resolution of the thrombus.8

Thrombosis

Thrombosis results from blood clotting within an artery, which can be caused by progressive atherosclerotic obstruction, hypercoagulability, or aortic or arterial dissection.

Atherosclerotic Obstruction

Thrombotic occlusion is most commonly the result of progressive atherosclerotic narrowing in peripheral arteries of the leg. Once a stenosis becomes critical, platelet thrombus develops on the stenotic lesion, leading to an acute arterial occlusion. The clinical manifestations are seldom as dramatic as those of embolization because the progressive process of atherosclerotic narrowing results in the development of robust collateral circulation. Patients with atherosclerosis deteriorate in a stepwise fashion as thrombosis supervenes on an arterial stenosis. The resulting symptoms of ischemia (usually the acute onset of claudication) improve as collateral vessels expand. Critical ischemia is the end result when this process occurs at multiple levels. Acute stroke or myocardial infarction is the result of atherosclerotic plaque disruption, which may be confirmed by plaque inspection at carotid endarterectomy or autopsy.6 In the extremities, it is not known whether plaque disruption is a cause of acute-on-chronic arterial thrombosis, because the offending plaque is rarely available for examination. It is possible, however, that the process of plaque disruption is the etiology in certain cases.

In patients with extensive atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, a reduction in cardiac output may produce acute limb ischemia by a global reduction in limb arterial perfusion. For example, if a patient with severe claudication develops complicated diverticulitis, the onset of shock may cause low cardiac output and result in acute critical limb ischemia in the absence of thrombosis. It is important to recognize this phenomenon because it is the underlying disease, not the leg, that needs urgent treatment.

Hypercoagulable States

In situ vessel thrombosis can also occur in the absence of atherosclerotic disease in states of hypercoagulability, low arterial flow, or hyperviscosity. These hypercoagulable states are associated predominantly with venous thrombosis, but thrombocythemia in particular can cause arterial occlusion, usually in small vessels. Malignant disease is also linked mainly to venous thrombosis, but several authors have observed an association with acute arterial ischemia.7 It may be worth screening patients with acute leg ischemia for an underlying malignancy. Because the vessel thrombosis is often a marker of advanced malignancy, the outcome in these patients is poor.

Vascular surgeons occasionally encounter heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, in which a patient on heparin develops progressive vessel thrombosis with a falling platelet count. Other hypercoagulable conditions that may cause arterial thrombosis and result in acute limb ischemia are discussed in Chapter 38.

Vasospasm

Primary Raynaud’s disease rarely, if ever, causes acute ischemia. Secondary Raynaud’s, due to underlying connective tissue disorder, can be acute and may present with digital ischemia. Open revascularization is seldom possible, and the key to a successful outcome is prompt diagnosis and treatment with intravenous or intra arterial infusion of a vasodilator or prostanoid. Digital ischemia can also follow intra-arterial injection, most commonly as a result of inadvertent injection of illicit drugs. Ischemia may be profound and irreversible, particularly if particulate material is injected. Treatment consists of anticoagulation to prevent secondary thrombosis and infusion of thrombolytics, vasodilators, or prostanoids, as appropriate.

Aortic or Arterial Dissection

Another condition that requires a high index of suspicion for diagnosis is aortic dissection, which may involve the aortic bifurcation and give the appearance of iliac artery thrombosis.9 These patients typically have chest or back pain and may be hypertensive. Another clinical clue is renal failure if the dissection involves the renal arteries. Isolated arterial dissections of vessels supplying the lower extremity are uncommon but can occur from traumatic or fibrodysplastic causes.

Bypass Graft Occlusion

Another significant cause of acute limb ischemia is the occlusion of an existing patent bypass graft. Clearly, the rate depends on how many bypass grafts exist in a community.10,11 In areas that are well endowed with vascular services, patients frequently present emergently with graft thrombosis. In the United Kingdom, a national survey in 1996 reported that graft or angioplasty occlusion was responsible for 15% of acute limb ischemia.12 The diagnosis is usually easy, and the cause is more likely to be thrombosis than embolism. Assessment and treatment are similar to that for native vessel ischemia, but decisions about treatment can be much more difficult because of the variety of options available (see Chapter 113).

Clinical Presentation

The symptoms caused by vascular occlusion depend on the size of the artery occluded and whether collaterals have developed beforehand. Sudden occlusion of a proximal artery without existing collaterals leads to an acute white leg, whereas occlusion of the superficial femoral artery in the presence of well-established collaterals may be entirely asymptomatic. This is borne out by the number of individuals who are found to have occult femoropopliteal occlusive disease on population screening. Acute ischemia affects sensory nerves first; therefore loss of sensation is one of the earliest signs of acute leg ischemia. Motor nerves are affected next, causing muscle weakness; then skin and finally muscles are affected by the reduction in arterial perfusion. This is why muscle tenderness is one of the end-stage signs of acute leg ischemia. Once ischemia is established, the skin’s initial pallor becomes dusky blue as capillary venodilatation occurs. At this stage, pressure over the discolored skin leaves it white because the vessels are still empty (Fig. 161-5). The terminal stage of skin ischemia is caused by extravasation of blood owing to capillary disruption; digital pressure over the discolored skin produces no blush. At this stage, the skin is nonviable, and revascularization of necrotic tissue risks compartment syndrome and renal failure without salvaging the extremity (Fig. 161-6).

Historical series of patients with acute leg ischemia reveal a preponderance of embolic occlusion, usually secondary to valvular heart disease; however, this cause has essentially been eradicated owing to modern cardiovascular surgical expertise.1–3 Today the usual cause of cardiac emboli is atrial fibrillation as a result of ischemic heart disease, possibly mediated by conduction abnormalities. This means that the affected population tends to be much older than it was 50 years ago, and patients often have established atherosclerotic disease of the arteries. This can produce the confusing picture of a patient with an embolus as well as peripheral arterial disease. Another effect is the gradual increase in the incidence of acute ischemia as the population ages.13,14

Clinical Assessment

The initial assessment of acute critical ischemia involves an evaluation of both the limb and the patient as a whole.

History

The severity of the initial symptoms depends on the severity of ischemia and can range from incapacitating pain to the sudden onset of mild claudication. Obviously, the more severe the ischemia, the faster the patient seeks medical attention. Severe acute ischemia is usually obvious, with extreme pain and loss of sensation and power in the limb. Less severe ischemia can be difficult to diagnose and may be confused with musculoskeletal pain, sciatica, and other causes of limb discomfort. The duration of symptoms is the most important part of the history; in patients with severe ischemia, irreversible muscle necrosis occurs within 6 to 8 hours if the condition is untreated. Patients with an acute white leg require urgent intervention. The symptoms of sensory loss and muscle pain are also evidence of critical ischemia.

The history should include an attempt to define the cause of the ischemia. Historically, patients with emboli had valvular heart disease but no evidence of peripheral vascular disease or other atherosclerotic conditions; however, the presence of atherosclerosis no longer rules out embolism. Patients with acute-on-chronic thrombosis often give a history of prior intermittent claudication in the ipsilateral or contralateral leg. A full medical history is important because it may reveal other associated diseases such as diabetes mellitus. Risk factors for atherosclerotic disease should be sought, including smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and family history.

Physical Findings

Examination of the leg is used to define the severity of the ischemia and is therefore fundamental. The well-known rule of Ps—pain, pallor, paresis, pulse deficit, paresthesia, and poikilothermia—remains a good guide to both symptoms and signs. The color of the skin reflects its vascular supply. Marble-white skin is associated with acute total ischemia. Slow capillary refill is a sign that at least a small degree of distal flow is present and runoff vessels are probably patent. Sensation may be lost completely and the foot may be numb, but more often there is loss of fine touch and proprioception, which should be tested specifically. Muscle tenderness, particularly in the calf, is a sign of advanced ischemia. Acute ischemia is associated with the loss of peripheral pulses, which also helps define the level of the occlusion. Palpable normal pulses in the contralateral leg points toward embolism as the cause.

A full vascular examination reveals the level of the occlusion by the loss of arterial pulsation. A strong pulse can, however, mask an occlusion at that level because of the water-hammer effect. Other possible sources of embolization may become apparent, such as aortic or popliteal aneurysm or cardiac abnormalities such as atrial fibrillation. Patients with acute leg ischemia are often older adults with multiple comorbidities, and a full physical examination should be undertaken because the final outcome may depend as much on associated conditions as on the severity of the leg ischemia.

Hand-held Doppler examination is also a basic part of the examination. Pedal arterial signals may be absent or reduced. The presence of normal biphasic signals excludes the diagnosis. Soft monophasic signals are associated with patent distal vessels but proximal arterial occlusion. Absent Doppler signals in the ankle arteries is a poor prognostic sign. The arteries may be patent but with little flow, or they may be occluded with thrombus. In severe ischemia, ankle Doppler pressures are impossible to measure, partly owing to the lack of signal but also because of muscle tenderness. In less severe ischemia, an ankle pressure of 30 to 50 mm Hg can be expected, and an ankle-brachial index of about 0.3 is diagnostic of subcritical acute ischemia. Doppler can also be used to examine the extremity veins. In particular, lack of a venous signal in the popliteal fossa suggests popliteal venous occlusion, which is a particularly poor prognostic sign in a patient with acute arterial ischemia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree