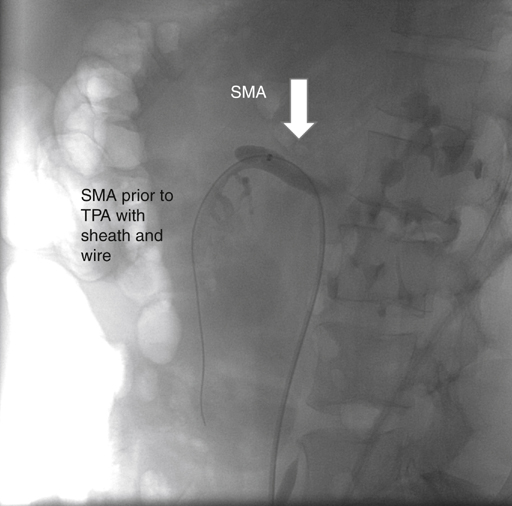

Acute embolic occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) produces a characteristic syndrome of abdominal pain in 75% to 90% of patients and is often accompanied by vomiting and gastrointestinal emptying (Figure 1). A detailed history and physical examination usually elicit several important features. Patients might have no antecedent symptoms of chronic mesenteric ischemia, but between 30% and 43% of patients present with acute embolic occlusions superimposed on chronic occlusive disease. Approximately 75% of patients have a history of an atrial tachyarrhythmia, 30% have a history of embolic events, and 20% have synchronous emboli in other arterial beds. Atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, left ventricular aneurysm, prosthetic heart valves, and rheumatic heart disease can lead to the formation of thrombus that serves as a source of peripheral emboli. The classic finding of pain out of proportion to physical examination occurs because visceral ischemic pain precedes the somatic pain that is associated with transmural ischemia and peritoneal irritation. Peritoneal signs and sepsis are late findings associated with increasing mortality rates.

Acute Embolic and Thrombotic Mesenteric Ischemia

Clinical Presentation

Acute Embolic Mesenteric Ischemia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree