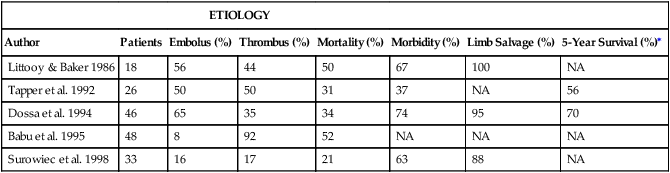

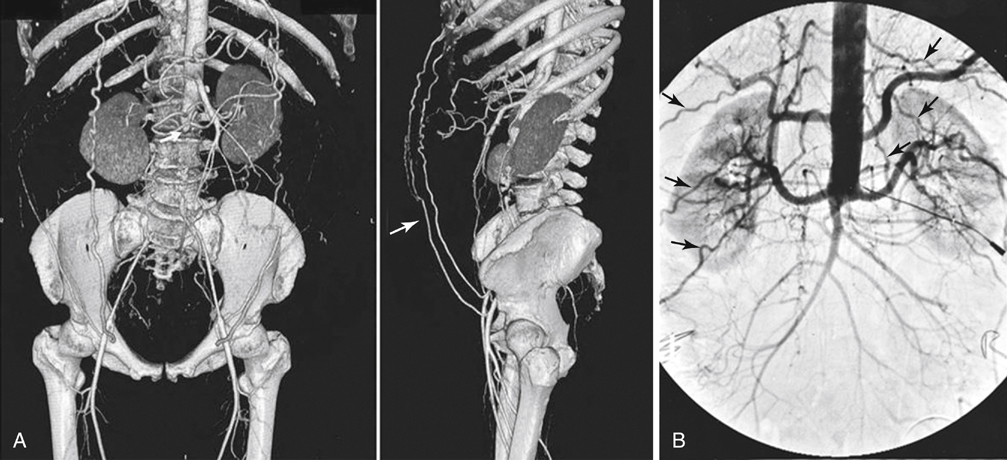

The leading causes of an acute aortic occlusion are an embolus originating from the heart and in-situ thrombosis in the setting of severe aortoiliac occlusive disease. Review of the largest published series (Table 1) suggests that the incidence of these two events are comparable and somewhat series dependent. Emboli usually occlude the aortic bifurcation as a saddle embolus with retrograde propagation of thrombus to the next patent vessel, usually the lowest renal artery. A variety of cardiac conditions and pathologies can result in peripheral emboli, including atrial fibrillation, acute myocardial infarction, valve diseases, prosthetic valves, dilated cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, and ventricular aneurysms. Massive or saddle emboli can also originate from aortic aneurysms, although this is distinctly less common. TABLE 1 Series of Acute Aortic Occlusions ∗Among those surviving the acute event. Babu SC, Shah PM, Nitahara J: Acute aortic occlusion—factors that influence outcome, J Vasc Surg 21:567–572, 1995; Dossa CD, Shepard AD, Reddy DJ, et al: Acute aortic occlusion. A 40-year experience, Arch Surg 129:603–607, 1994; Littooy FN, Baker WH: Acute aortic occlusion—a multifaceted catastrophe, J Vasc Surg 4:211–216, 1986; Surowiec SM, Isiklar H, Sreeram S, et al: Acute occlusion of the abdominal aorta, Am J Surg 176:193–197, 1998; Tapper SS, Jenkins JM, Edwards WH, et al: Juxtarenal aortic occlusion, Ann Surg 215:443–449, 1992. In-situ thrombosis in the setting of severe aortoiliac occlusive disease is often precipitated by an exacerbating event such as dehydration or diminished cardiac output from a myocardial infarction. Similar to the scenario with saddle emboli, the thrombotic process usually extends to the level of the renal arteries, with rare suprarenal extension of the thrombus. A number of other mechanisms have been implicated and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an acute aortic occlusion given the appropriate clinical setting (Table 2). These include acute aortic dissections, thrombosis secondary to a hypercoaguable state, trauma, and postoperative complications after aortic reconstruction. Among the hypercoagulable states, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia merits consideration given the high prevalence of exogenous heparin use in the hospital setting. A small number of interesting collections of case reports have described several additional rare etiologies. TABLE 2 Reported Causes of Acute Aortic Occlusions The diagnosis of an acute aortic occlusion can usually be made by history and physical examination and confirmed with the appropriate imaging study if there is any question about the diagnosis or the initial treatment approach. Computed tomography (CT) arteriography has emerged as the definitive diagnostic test for acute aortic occlusion (Figure 1). CT arteriography image acquisition times are rapid, and the quality of the images with the newer-generation multi-slice technology is excellent. Furthermore, it overcomes many of the limitations of catheter-based arteriography in the setting of an acute aortic occlusion, including the need to cannulate the brachial artery and the potential limited contrast delivery for vessel visualization below the aortic occlusion. Admittedly, the decision to obtain a confirmatory imaging study must be balanced by the additional risk in terms of the potential delay of the definitive treatment and the associated contrast nephrotoxicity. Given the relative ease of obtaining a CT arteriogram in our center, we have a low threshold for obtaining such a study in the setting of a presumed aortic occlusion, particularly if there is any concern about visceral and/or renal involvement. The slight risk or delay appears justified by the additional anatomic information provided by the study.

Acute Aortic Occlusion

Etiology

ETIOLOGY

Author

Patients

Embolus (%)

Thrombus (%)

Mortality (%)

Morbidity (%)

Limb Salvage (%)

5-Year Survival (%)∗

Littooy & Baker 1986

18

56

44

50

67

100

NA

Tapper et al. 1992

26

50

50

31

37

NA

56

Dossa et al. 1994

46

65

35

34

74

95

70

Babu et al. 1995

48

8

92

52

NA

NA

NA

Surowiec et al. 1998

33

16

17

21

63

88

NA

Category

Example

Embolic

Cardiogenic (e.g., Afib, valve disease)

In-situ thrombosis

PAD, plaque rupture, AAA

Dissection

Type B aortic dissection

Postsurgical

Bypass graft thrombosis (e.g., ABF), endograft collapse (i.e., TEVAR/EVAR, iliac stents)

Metabolic

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Infectious

Aspergillus spp, Candida spp

Inflammatory

Arteritis

Low-flow state

Dehydration, CHF, diarrhea, vomiting

Hypercoagulable state

HIT, thrombophilic state (e.g., cancer)

Trauma

Aortic transection (e.g., lap belt injury)

Miscellaneous

Umbilical artery catheterization, tension pneumoperitoneum, lymphoma, SBO

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine