Acute and Subacute Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

Marie-Christine Aubry, M.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Seth Kligerman, M.D.

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Terminology

One of the first uses of a term related to “organizing pneumonia (OP)” in the context of interstitial lung disease was by Liebow and Carrington, who designated “bronchiolitis obliterans with clinical interstitial pneumonia” as one of the five idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs).1 The concept of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) originated in 1983, when Davison et al. described a clinicopathologic entity afflicting eight patients with malaise, weight loss, elevated sedimentation rate, and diffuse lung infiltrates.2 COP defined a noninfectious, steroid-responsive condition histologically mimicking postinfectious organizing pneumonia; airway or bronchiolar involvement was not stressed. Interestingly, in the same year (1983), Davison and Epstein described “relapsing organizing pneumonitis” in a patient with CREST syndrome.3 Soon thereafter, Epler et al. described a larger series of 50 patients with histologic documented “bronchiolitis obliterans with patchy organizing pneumonia,” which was likewise idiopathic and noninfectious and steroid responsive. This series marked the first use of the term “bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia,” or BOOP.4 The authors emphasized the intraluminal morphology of BOOP nicely describing the histologic finding of “polypoid masses of granulation tissue in lumens of small airways, alveolar ducts, and some alveoli” while recognizing the restrictive physiology on lung function, as seen in interstitial lung disease.

The predominant airspace nature of BOOP led many authors to question its validity as an interstitial lung disease. Furthermore, the bronchiolitis obliterans of BOOP was unfortunately confused with a completely different and purely obstructive airway disease called constrictive bronchiolitis, also known as bronchiolitis obliterans.

The American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society maintained BOOP as an IIP since BOOP can clinically present as and enters the differential diagnosis of IIPs. Due to the confusion generated by the terminology, they also suggested dropping the BO part of BOOP and use the terminology of COP to designate a disease that is idiopathic and histologically characterized by “organization within alveolar ducts and alveoli with or without organization within bronchioles.”5

Clinical Findings

COP is generally a disease of subacute onset, usually <3-month duration. Overall, it represents between 4% and 12% of IIPs.6 There is an equal sex distribution, and more patients are nonsmokers than smokers.5 The mean age at onset is 55 years.5 Patients present with shortness of breath and cough, which may be productive with clear sputum. Systemic symptoms are common. Finger clubbing is rare, and there is often increased C-reactive protein and sedimentation rate.5 Lung parameters show usually a restrictive defect with moderately reduced carbon monoxide transfer factor, mild airflow obstruction, and mild hypoxemia.5

The diagnosis of cryptogenic OP requires a lack of association with other diseases such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis, infection, tumors, drugs, connective tissue diseases, rejection, aspiration, and eosinophilic pneumonia (EP) (Chapter 26).6

Radiologic Findings

There are numerous CT patterns described with OP ranging from a focal nodule to diffuse fibrotic lung disease. Although focal disease can occur, most patients with COP and secondary OP present with a diffuse parenchymal abnormality.

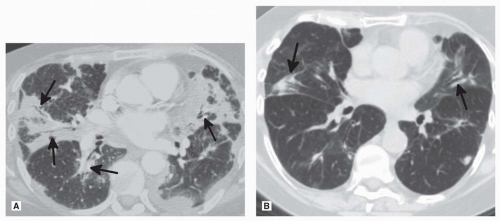

Series have shown that high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) shows ground-glass opacities (GGO) (60% to 85%) and consolidation (70% to 90%) that may be peribronchovascular or peripheral (Fig. 19.1).4,5,7 These are often patchy with lower zone predominance.6 In 90% of cases, there are air bronchograms in the areas of consolidation.5 The distribution may be subpleural or peribronchial, with small nodules involving bronchovascular bundles. In 15%, the radiologic presentation is that of multiple large nodules.5 Rarely, COP may mimic lung cancer, presenting as a single nodule with irregular borders with positive emission tomography (PET) positivity.8 The reverse halo sign is typical but not pathognomonic. Pleural effusion is uncommon. In contrast to nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) or usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), there is no volume loss or honeycombing.9

Tissue Sampling

In the appropriate clinical and radiologic confirm, a transbronchial biopsy may be sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of OP.10 However, an open lung or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery is the preferred method of tissue sampling if a broader differential diagnosis is considered clinically. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) shows increased lymphocyte proportion of total cells, up to 40%, and decreased CD4/CD8 ratio, similar to NSIP.9

Microscopic Findings

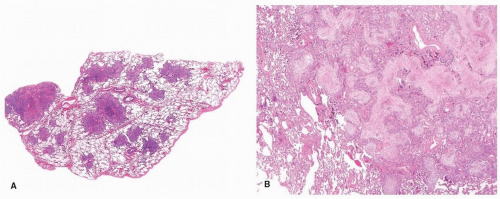

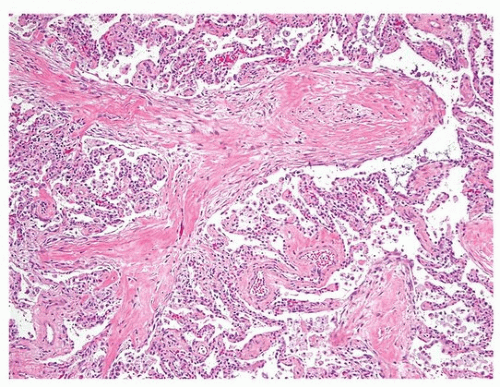

The histologic findings are those of OP (Chapter 5). The dominant feature is the proliferation of fibroblast/myofibroblast in a loose myxoid stroma forming intraluminal plugs (Fig. 19.2). There may be an associated chronic interstitial inflammation, with reactive pneumocytes, and increased alveolar macrophages, some of which may be foamy. However, these findings are limited to the areas of lung with the intraluminal fibroblast plugs. Away from these airspace changes, the lung parenchyma appears normal. Occasionally, there is increased collagen deposition within the intraluminal plugs and replacement of the fibroblasts (Fig. 19.3). Over time, this collagen fibrosis may get incorporated into the alveolar septa. These features may pertain to a worse prognosis.11 Fibrin may be focally present but not conspicuous.

Prognosis and Treatment

The treatment of COP is steroids, which result in clearing of symptoms in the majority of patients. Although the radiologic abnormalities are

thought to typically resolve, a study suggests that some residual findings may persist in the majority of patients.7 There may be recurrence after cessation of steroid therapy, or if reduced below 14 mg/day. Deaths due to COP are considered rare.6 The concept of progression of COP to fibrotic lung disease is controversial and not well documented. One study comparing progressive COP with steroid-responsive COP found that progressive disease histologically had scarring and remodeling of the background lung parenchyma, without honeycombing.11 From this study, it is not possible to ascertain if some patients had preexisting fibrotic lung disease. Indeed, patients with UIP diagnosed on explant may have a prior wedge biopsy with prominent areas of “BOOP.”12 Therefore, in general, most cases of COP described as progressing to UIP may have an initial wrong diagnosis.5 However, in the series from Yousem et al., there were a few cases that had a premortem biopsy and autopsy, confirming the absence of a chronic fibrosing lung disease such as NSIP or UIP, therefore supporting the concept of fibrosing OP.

thought to typically resolve, a study suggests that some residual findings may persist in the majority of patients.7 There may be recurrence after cessation of steroid therapy, or if reduced below 14 mg/day. Deaths due to COP are considered rare.6 The concept of progression of COP to fibrotic lung disease is controversial and not well documented. One study comparing progressive COP with steroid-responsive COP found that progressive disease histologically had scarring and remodeling of the background lung parenchyma, without honeycombing.11 From this study, it is not possible to ascertain if some patients had preexisting fibrotic lung disease. Indeed, patients with UIP diagnosed on explant may have a prior wedge biopsy with prominent areas of “BOOP.”12 Therefore, in general, most cases of COP described as progressing to UIP may have an initial wrong diagnosis.5 However, in the series from Yousem et al., there were a few cases that had a premortem biopsy and autopsy, confirming the absence of a chronic fibrosing lung disease such as NSIP or UIP, therefore supporting the concept of fibrosing OP.

Acute Interstitial Pneumonia

Terminology

Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) was initially described by Katzenstein et al. to designate a disease that differed from chronic interstitial pneumonia by an acute onset and rapid course.13 AIP was likely “Hamman-Rich syndrome” based on this initial description of

four patients with rapidly fatal interstitial fibrotic lung disease.14 The underlying pathology is diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), morphologically indistinct from DAD due to an identifiable underlying cause (Chapters 4 and 21).5,15,16,17

four patients with rapidly fatal interstitial fibrotic lung disease.14 The underlying pathology is diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), morphologically indistinct from DAD due to an identifiable underlying cause (Chapters 4 and 21).5,15,16,17

Clinical Findings

The initially reported eight cases of AIP were characterized by sudden onset of respiratory symptoms, leading to respiratory failure and death, usually within 2 months of onset.13 Subsequent series have shown that the median time from first symptom to severe dyspnea is <3 weeks.5,17 Patients may have a prior systemic illness suggestive of inflammatory etiology. AIP occurs over a wide age range, with a mean age of ˜50 years, without gender predilection. Pulmonary function tests show a restrictive pattern with reduced diffusing capacity, and hypoxemia develops early and progresses rapidly to respiratory failure.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree