Chapter 47 Acute Abdomen

The term acute abdomen refers to signs and symptoms of abdominal pain and tenderness, a clinical presentation that often requires emergency surgical therapy. This challenging clinical scenario requires a thorough and expeditious workup to determine the need for operative intervention and initiate appropriate therapy. Many diseases, some of which are not surgical or even intra-abdominal,1 can produce acute abdominal pain and tenderness. Therefore, every attempt should be made to make a correct diagnosis so that the therapy selected, often a laparoscopy or laparotomy, is appropriate.

The diagnoses associated with an acute abdomen vary according to age and gender.2 Appendicitis is more common in younger individuals, whereas biliary disease, bowel obstruction, intestinal ischemia and infarction, and diverticulitis are more common in older adults. Most surgical diseases associated with an acute abdomen result from infection, obstruction, ischemia, or perforation.

Nonsurgical causes of an acute abdomen can be divided into three categories, endocrine and metabolic, hematologic, and toxins or drugs (Box 47-1).3 Endocrine and metabolic causes include uremia, diabetic crisis, addisonian crisis, acute intermittent porphyria, acute hyperlipoproteinemia, and hereditary Mediterranean fever. Hematologic disorders include sickle cell crisis, acute leukemia, and other blood dyscrasias. Toxins and drugs causing an acute abdomen include lead and other heavy metal toxins, narcotic withdrawal, and black widow spider poisoning. It is important to consider these possibilities when evaluating a patient with acute abdominal pain.

Because of the potential surgical nature of the acute abdomen, an expeditious workup is necessary (Box 47-2). The workup proceeds in the usual order—history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. Although imaging studies have increased the accuracy with which the correct diagnosis can be made, the most important part of the evaluation remains a thorough history and careful physical examination. Laboratory and imaging studies are usually needed, but are directed by the findings on history and physical examination.

Box 47-2 Surgical Acute Abdominal Conditions

Hemorrhage

Leaking or ruptured arterial aneurysm

Bleeding gastrointestinal diverticulum

Arteriovenous malformation of gastrointestinal tract

Aortoduodenal fistula after aortic vascular graft

Anatomy and Physiology

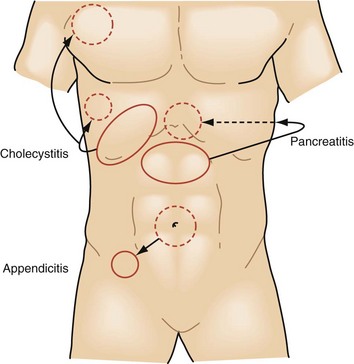

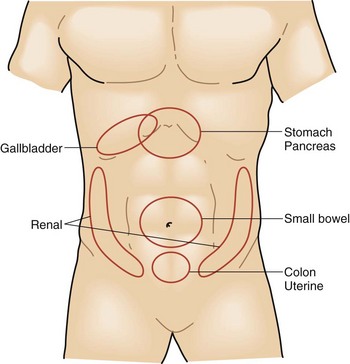

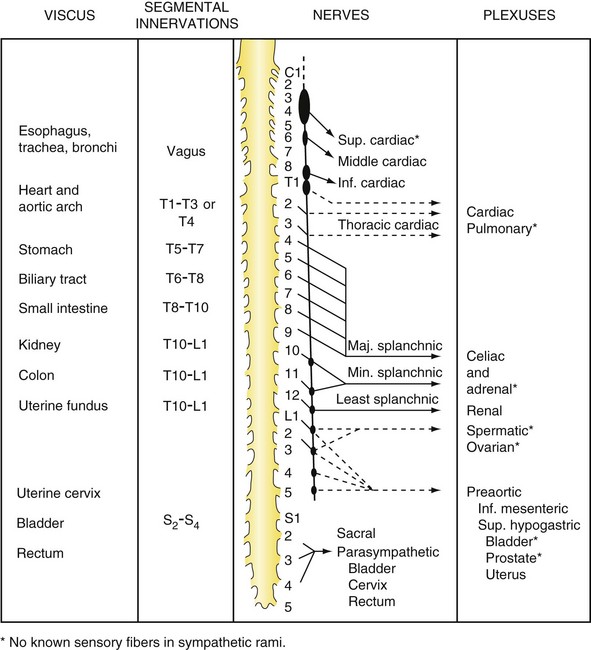

Abdominal pain is divided into visceral and parietal components. Visceral pain tends to be vague and poorly localized to the epigastrium, periumbilical region, or hypogastrium, depending on its origin from the primitive foregut, midgut, or hindgut (Fig. 47-1). It is usually the result of distention of a hollow viscus. Parietal pain corresponds to the segmental nerve roots innervating the peritoneum and tends to be sharper and better localized. Referred pain is pain perceived at a site distant from the source of stimulus. For example, irritation of the diaphragm may produce pain in the shoulder. Common referred pain sites and their accompanying sources are listed in Box 47-3. Determining whether the pain is visceral, parietal, or referred is important and can usually be done with a careful history.

FIGURE 47-1 Sensory innervation of the viscera.

(From White JC, Sweet WH: Pain and the neurosurgeon, Springfield, Ill, 1969, Charles C Thomas, p 526.)

Peritonitis is peritoneal inflammation of any cause. It is usually recognized on physical examination by severe tenderness to palpation, with or without rebound tenderness, and guarding. Peritonitis is usually secondary to an inflammatory insult, most often a gram-negative infection with an enteric organism or anaerobe. It can result from noninfectious inflammation; a common example is pancreatitis. Primary peritonitis occurs more commonly in children and is most often caused by Pneumococcus or hemolytic Streptococcus spp.4 Adults with end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis can develop infections of their peritoneal fluid, with the most common organisms being gram-positive cocci. Adults with ascites and cirrhosis can develop primary peritonitis and, in these cases, the organisms are usually Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp.

History

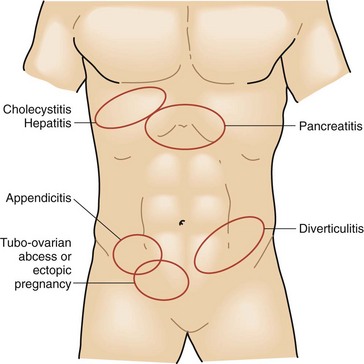

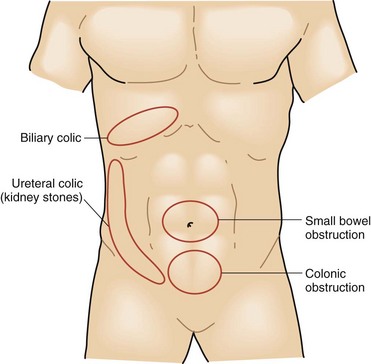

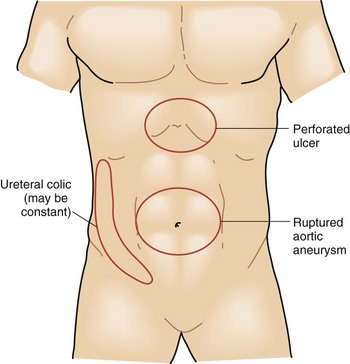

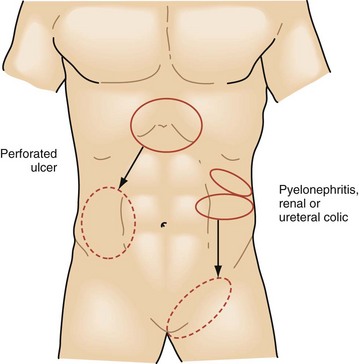

The intensity and severity of the pain are related to the underlying tissue damage. Sudden onset of excruciating pain suggests conditions such as intestinal perforation or arterial embolization with ischemia, although other conditions, such as biliary colic, can present suddenly as well. Pain that develops and worsens over several hours is typical of conditions of progressive inflammation or infection such as cholecystitis, colitis, and bowel obstruction. The history of progressive worsening versus intermittent episodes of pain can help differentiate infectious processes that worsen with time compared with the spasmodic colicky pain associated with bowel obstruction, biliary colic from cystic duct obstruction, or genitourinary obstruction (Figs. 47-2 to 47-4).

Equally as important as the character of the pain is its location and radiation. Tissue injury or inflammation can trigger visceral and somatic pain. Solid organ visceral pain in the abdomen is generalized in the quadrant of the involved organ, such as liver pain across the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Small bowel pain is perceived as poorly localized periumbilical pain, whereas colon pain is centered between the umbilicus and pubis symphysis. As inflammation expands to involve the peritoneal surface, parietal nerve fibers from the spine allow for focal and intense sensation. This combination of innervation is responsible for the classic diffuse periumbilical pain of early appendicitis that later shifts to become an intense focal pain in the right lower abdomen at McBurney’s point. If the physician focuses on the character of the current pain and does not thoroughly investigate its onset and progression, he or she will miss these strong historical clues (Figs. 47-5 and 47-6). Pain may also extend well beyond the diseased site. The liver shares some of its innervation with the diaphragm and may create referred pain to the right shoulder from the C3-C5 nerve roots. Genitourinary pain is another source of pain that commonly has a radiating pattern. Symptoms are primarily in the flank region, originating from the splanchnic nerves of T11-L1, but pain often radiates to the scrotum or labia via the hypogastric plexus of S2-S4.

Little has changed in the technique or goals of history taking since Dr. Zachary Cope first published his classic paper on the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in 1921.5 An exception is the application of computers to history taking, which has been extensively studied in Europe.6–10 Data were collected by physicians on detailed standardized forms during history and physical examinations and entered into computers programmed with a medical database of diseases and their associated signs and symptoms. The computer-generated diagnosis, based on mathematical probabilities, was as much as 20% more accurate than physicians who didn’t use computers to help arrive at a diagnosis. Statistically significant improvement was identified in regard to a timely laparotomy, shortened hospital stay, and reduced need for surgery and hospitalization. However, it should be noted that statistically significant improvements in accuracy and efficiency can be realized without computer assistance if similar standardized forms are used for data collection. This has also been observed in the settings of trauma and critical care.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should always begin with a general inspection of the patient, to be followed by inspection of the abdomen itself. Patients with peritoneal irritation will experience worsened pain with any activity that moves or stretches the peritoneum. These patients will typically lie very still in bed during the evaluation and often maintain flexion of their knees and hips to reduce tension on the anterior abdominal wall. Disease states that cause pain without peritoneal irritation, such as ischemic bowel or ureteral or biliary colic, typically cause patients to shift and fidget in bed continually while trying to find a position that lessens their discomfort (Fig. 47-7). Other important clues such as pallor, cyanosis, and diaphoresis may also be observed during the general inspection.

Numerous unique physical findings have come to be associated with specific disease conditions and are well described as examination signs (Table 47-1). Murphy’s sign of acute cholecystitis results when inspiration during palpation of the right upper quadrant results in sudden worsening of pain because of descent of the liver and gallbladder toward the examiner’s hand. Several signs help localize the site of underlying peritonitis, including obturator, psoas, and Rovsing’s signs. Others, such as the Fothergill and Carnett signs, help distinguish intra-abdominal disease from that of the abdominal wall.

Table 47-1 Abdominal Examination Signs

| SIGN | DESCRIPTION | DIAGNOSIS OR CONDITION |

|---|---|---|

| Aaron | Pain or pressure in epigastrium or anterior chest with persistent firm pressure applied to McBurney’s point | Acute appendicitis |

| Bassler | Sharp pain created by compressing appendix between abdominal wall and iliacus | Chronic appendicitis |

| Blumberg | Transient abdominal wall rebound tenderness | Peritoneal inflammation |

| Carnett | Loss of abdominal tenderness when abdominal wall muscles are contracted | Intra-abdominal source of abdominal pain |

| Chandelier | Extreme lower abdominal and pelvic pain with movement of cervix | Pelvic inflammatory disease |

| Charcot | Intermittent right upper abdominal pain, jaundice, and fever | Choledocholithiasis |

| Claybrook | Accentuation of breath and cardiac sounds through abdominal wall | Ruptured abdominal viscus |

| Courvoisier | Palpable gallbladder in presence of jaundice | Periampullary tumor |

| Cruveihier | Varicose veins at umbilicus (caput medusa) | Portal hypertension |

| Cullen | Periumbilical bruising | Hemoperitoneum |

| Danforth | Shoulder pain on inspiration | Hemoperitoneum |

| Fothergill | Abdominal wall mass that does not cross midline and remains palpable when rectus contracted | Rectus muscle hematomas |

| Grey Turner | Local areas of discoloration around umbilicus and flanks | Acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis |

| Iliopsoas | Elevation and extension of leg against resistance creates pain | Apppendicitis with retrocecal abscess |

| Kehr | Left shoulder pain when supine and pressure placed on left upper abdomen | Hemoperitoneum (especially from splenic origin) |

| Mannkopf | Increased pulse when painful abdomen palpated | Absent if malingering |

| Murphy | Pain caused by inspiration while applying pressure to right upper abdomen | Acute cholecystitis |

| Obturator | Flexion and external rotation of right thigh while supine creates hypogastric pain | Pelvic abscess or inflammatory mass in pelvis |

| Ransohoff | Yellow discoloration of umbilical region | Ruptured common bile duct |

| Rovsing | Pain at McBurney’s point when compressing the left lower abdomen | Acute appendicitis |

| Ten Horn | Pain caused by gentle traction of right testicle | Acute appendicitis |