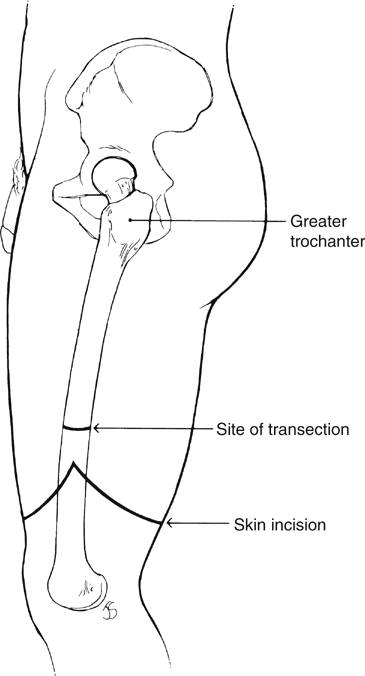

The choice of incision is dictated by the surgeon’s preference. We prefer a fish-mouth incision with equal-length anterior and posterior flaps because of the early cosmetic appearance (Figure 1). However, the circumferential incision and the fish-mouth incision with sagittal flaps are both acceptable. Notably, the muscle and other soft tissues atrophy and remodel during the early postoperative period so that the residual extremity looks essentially the same at 6 months regardless of the initial incision. The incision is usually made over the distal two thirds of the thigh in an attempt to preserve as much of the femur length as possible if there is any chance that the patient will walk on a prosthesis. The distal aspect of the anterior and posterior flap of the fish-mouth incision is commonly cited two finger breadths proximal to the patella, with the angle of the incision in the mid portion of the thigh, roughly 3 to 4 cm proximal to the most distal extent. The planned incision is marked on the skin, and then the anterior skin and soft tissues are incised along the planes of the skin mark.

Above-Knee Amputation and Hip Disarticulation

Above-Knee Amputation

Indications

Operative Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Above-Knee Amputation and Hip Disarticulation