Evaluation of PES transit abnormalities

Evaluation of esophageal mucosal pathology

Evaluation of esophageal motility

Evaluation of obstructing esophageal pathology (web, ring, stricture)

Evaluation of diverticuli

Evaluation of hiatal hernia

Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux

Evaluation of Pharyngoesophageal Segment (PES) Transit Abnormalities

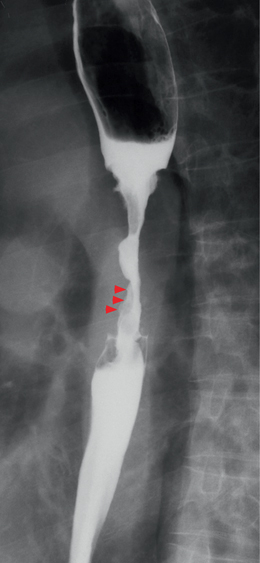

The initial evaluation of the VFE begins with an assessment of transit through the pharyngoesophageal segment (PES) . The presence of PES narrowing from cricopharyngeus muscle dysfunction (bar), web, stricture, or neoplasm is noted (Chap. 10). The right anterior oblique (RAO) view afforded by the VFE provides a unique and unobstructed view of PES anatomy and barium flow. Subtle pathology, such as a small cricopharyngeal web missed on lateral fluoroscopic view can be identified on the RAO view of the VFE (Fig. 11.1). After the PES is evaluated, the VFE evaluation proceeds with an assessment of esophageal mucosal pathology .

Fig. 11.1

A right anterior oblique view on videofluoroscopic esophagram of a small esophageal web (red arrows) that was missed on the lateral fluoroscopic view of a videofluoroscopic swallow study

Evaluation of Esophageal Mucosal Pathology

The double contrast phase of the study highlights mucosal pathology that may otherwise be missed. The normal distended esophagus has a smooth homogenous contour (Fig. 11.2). Partially collapsed mucosal relief views may reveal mucosal changes signifying underlying pathology such as neoplasm or esophagitis (Figs. 11.3 and 11.4). The most common cause of esophagitis is gastroesophageal reflux (peptic esophagitis). Esophageal inflammation and edema can result in a nodular appearance on VFE (Fig. 11.4). The VFE is poorly sensitive to diagnose mild esophagitis. Infectious esophagitis is much less common than reflux esophagitis. The most common cause of infectious esophagitis is candida. Candida esophagitis results in a characteristic granular appearance on VFE (Figs. 11.5 and 11.6). Other much less common causes of infectious esophagitis include herpes and cytomegalovirus (CMV) (Figs. 11.7 and 11.8). Eosinophillic esophagitis (EoE) is a rapidly increasing atopic cause of solid food dysphagia . Although the diagnosis of EoE is made on endoscopic biopsy displaying > 20 eosinophils per high-power field, there is a characteristic appearance on VFE that is highly suggestive of EoE. The distinguishing finding is that of segmental esophageal strictures giving the appearance of a corrugated or ringed esophagus (Figs. 11.9 and 11.10). In the absence of a ringed esophagus, a small caliber esophagus also suggests the presence of fibrotic narrowing secondary to the eosinophilic infiltrate (Fig. 11.11) .

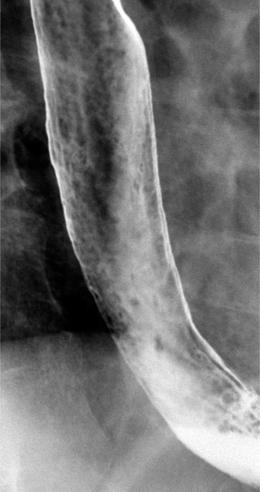

Fig. 11.2

Normal mucosal appearance of the distended esophagus (red arrows)

Fig. 11.3

Mucosal irregularities (red arrowheads) in a person with esophageal cancer and a 6-cm stricture of the cervical esophagus. (Source: Cardiovasc and Intervent Radiol 31(3):663–668, 2008)

Fig. 11.4

Nodularity of the distal third of the esophagus suggesting the presence of inflammation and reflux esophagitis. (Source: Radiographic Evaluation of the Esophageal Phase of Swallowing Publisher: Springer. Authors: Levine, Marc S. Book title: Manual of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Techniques for Disorders of Deglutition. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3779-6_4. Published Date: 2013-01-01)

Fig. 11.5

Irregular granular esophageal mucosa suggestive of candida esophagitis. (Source: Gastrointestinal Imaging Publisher: Springer Authors: Lee, Susanna I. Thrall, James H. Book title: Choosing the Correct Radiologic Test DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-15772-1_4 Published Date: 2013-01-01)

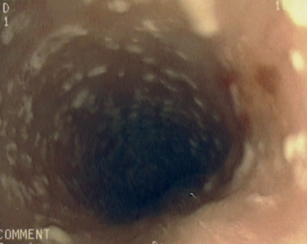

Fig. 11.6

Candida esophagitis seen during esophagoscopy

Fig. 11.7

Herpes esophagitis. Multiple small ulcerations, each surrounded by a ring of lucency due to edema, are present in the distal esophagus. (Source: Gastrointestinal infection in the immunocompromised (AIDS) patient Publisher: Springer Authors: Reeders, J. W. A. J. Yee, J. Gore, R. M. Miller, F. H. Megibow, A. J. Journal title: European Radiology Supplements DOI: 10.1007/s00330-003-2065-7 Published Date: 2004-03-01)

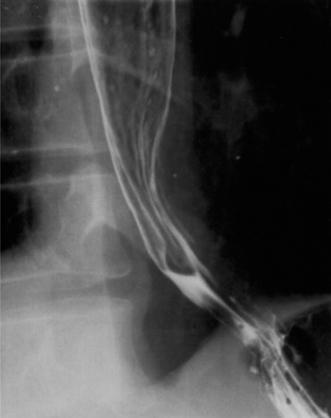

Fig. 11.8

Findings of cytomegalovirus esophagitis include longitudinal, semilunar, deep, penetrating ulcerations at the mid-esophagus opposite each other. a Single-contrast and b double-contrast esophagogram. c Endoscopy. (Source: Gastrointestinal infection in the immunocompromised (AIDS) patient Publisher: Springer Authors: Reeders, J. W. A. J. Yee, J. Gore, R. M. Miller, F. H. Megibow, A. J. Journal title: European Radiology Supplements DOI: 10.1007/s00330-003-2065-7 Published Date: 2004-03-01)

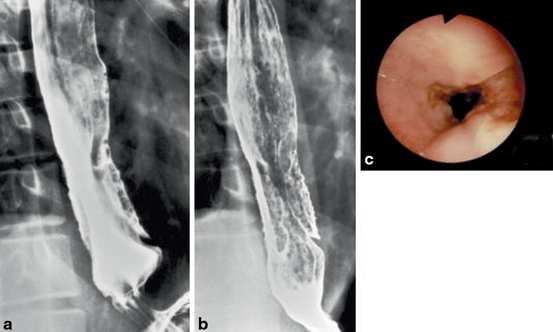

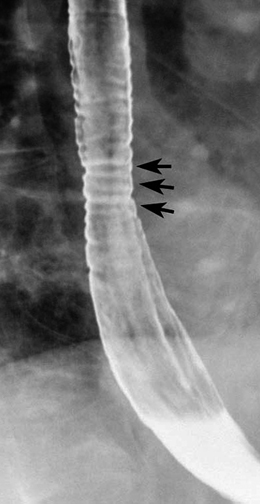

Fig. 11.9

Eosinophilic esophagitis with ringed esophagus. There is a smooth, tapered stricture in the mid-esophagus with distinctive ring-like indentations (arrows) in the region of the stricture. (Source: Radiographic Evaluation of the Esophageal Phase of Swallowing. Publisher: Springer Levine, Marc S. Book title: Manual of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Techniques for Disorders of Deglutition. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3779-6_4. Published Date: 2013-01-01)

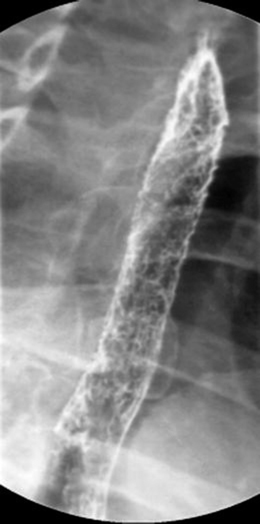

Fig. 11.10

Endoscopic image of eosinophilic esophagitis displaying characteristic rings and giving the appearance of a corrugated or trachealized esophagus

Fig. 11.11

Small-caliber esophagus characteristic of eosinophilic esophagitis

An evaluation of the mucosa concludes with an assessment of the esophageal mucosal folds. The longitudinal mucosal folds of the esophagus are normally thin, straight, and less than 2 mm in width. Prominent mucosal folds indicate esophageal inflammation and suggest the presence of esophagitis (Figs. 11.12 and 11.13). Esophageal varices produce an irregular, serpiginous, almost colonic appearance to the distal esophagus and mucosal folds (Fig. 11.14). After the evaluation of mucosal pathology, the systematic analysis of the VFE proceeds with an assessment of esophageal motility .

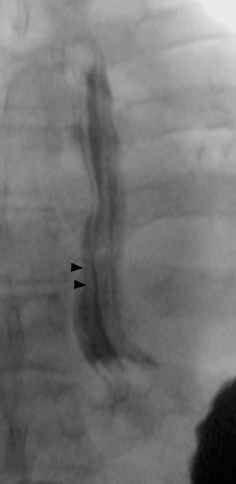

Fig. 11.12

Prominent esophageal mucosal folds (black arrowheads) on anterior-posterior fluoroscopic view suggestive of reflux esophagitis

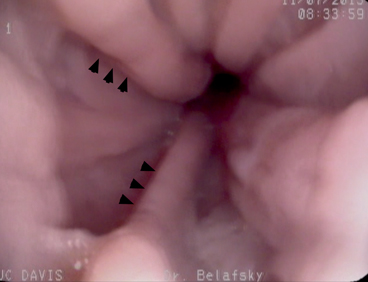

Fig. 11.13

Prominent esophageal mucosal folds on esophagoscopy (black arrowheads) indicating reflux esophagitis

Fig. 11.14

Esophageal varices seen in a prone single-contrast spot image showing uphill esophageal varices as serpiginous longitudinal defects in the lower esophagus. (Source: Radiographic Evaluation of the Esophageal Phase of Swallowing Publisher: Springer. Authors: Levine, Marc S. Book title: Manual of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Techniques for Disorders of Deglutition. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3779-6_4 Published Date: 2013-01-01)

Evaluation of Esophageal Motility

An evaluation of esophageal motility is an essential aspect of the comprehensive VFE. Motility abnormalities can generally be classified into IEM, esophageal spasm, scleroderma, or achalasia. IEM is the much more frequent diagnosis. IEM is further classified on VFE as mild or severe. Motility assessment begins with an evaluation of primary peristalsis. Primary peristalsis is evaluated by assessing the primary stripping wave and esophageal stasis. This is initially performed in the upright and then prone position (Chap. 3). It is essential that the patient be instructed to consume the barium bolus in one effortful swallow. Taking additional swallows will terminate the esophageal contraction wave and give the impression of dysmotility when peristalsis is normal (deglutitive inhibition). Primary peristalsis is visualized fluoroscopically as a stripping wave. A normal esophageal stripping wave transmits a bolus along the esophagus at approximately 2 cm/s. A bolus should clear a normal 25 cm esophagus in less than 15 s. The barium should proceed throughout its entire length in one smooth stripping motion. The presence of secondary peristalsis is also evaluated. Secondary peristalsis is a contraction that originates in the esophagus as a response to esophageal distention or chemical (acid) stimulation. Secondary peristalsis on VFE is assessed in response to barium stasis within the esophagus . Secondary peristalsis should strip and clear the esophagus of retained barium without the patient initiating a swallow in the pharynx. Barium stasis in the esophagus > 15 s or alterations in the primary or secondary stripping wave are indications of IEM. The degree of peristaltic abnormality is classified as mild, severe (profound), or absent. In patients with profound esophageal dysmotility, it is essential to recognize the presence of any stripping wave. A complete absence of a primary and secondary stripping wave suggests achalasia and a complete absence of a stripping wave in the smooth muscle esophagus only (distal 2/3) suggests scleroderma. The visualization of a single primary or secondary stripping wave suggests a diagnosis other than achalasia. The presence of tertiary peristalsis is then evaluated. Tertiary peristalsis is simultaneous, isolated, nonperistaltic esophageal contractions (Fig. 6.8 and Fig. 11.15) that occur irrespective of coordinated peristalsis. They are nonpropulsive and are considered a sign of esophageal dysmotility. Profound tertiary contractions can be seen in esophageal spasm and give the appearance of a corkscrew esophagus (Figs. 11.16 and 11.17). Tertiary contractions and esophageal spasm may be associated with underlying gastroesophageal reflux .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree