Abdominal Vascular Trauma

Mark R. Hemmila

Paul A. Taheri

Traumatic injury to the abdominal vasculature represents a challenging problem that carries with it a high rate of mortality and morbidity. The initial management of all trauma patients should follow the established guidelines for the primary and secondary survey as published by the American College of Surgeons and taught in the Advanced Trauma Life Support Course (ATLS®). Prompt control of hemorrhage, coordinated with resuscitation, and repair of injuries is the time-honored algorithm of trauma surgeons. Abdominal vasculature injuries are often accompanied by injury to adjacent solid or hollow abdominal organs. Surgeons should follow an operative approach that provides adequate exposure, rapid identification of all injuries, expedient prioritization of those injuries requiring treatment, and relies on sound clinical judgment to correct all significant problems encountered.

Diagnostic Considerations

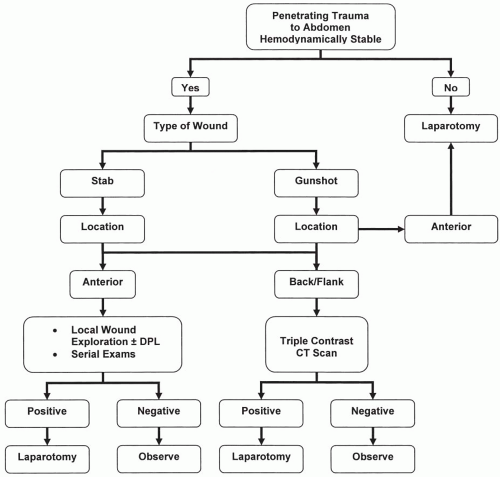

A history of the events surrounding the trauma should be obtained from the patient or emergency medical personnel. The physical finding of hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg) unresponsive to intravenous fluid administration may necessitate an abbreviated workup and immediate transfer to the operating room in a patient with obvious abdominal injury. Ultrasound examination (FAST, focused assessment with sonography for trauma) of the abdomen in the trauma bay as part of the primary survey can rapidly detect the presence of hemoperitoneum. This test has largely supplanted the use of diagnostic peritoneal lavage and resulted in fewer nontherapeutic laparotomies. If the patient is hemodynamically stable or can be stabilized with infusion of intravenous fluid, an abdominal pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan is the gold standard for evaluating the traumatically injured patient with a blunt mechanism of injury. Patients with penetrating injuries should undergo local wound exploration to evaluate for fascial penetration. If the fascia has been violated, abdominal exploration is usually mandatory except in highly selected instances. Recently, articles have appeared in the literature advocating the use of triple-contrast helical CT scanning in the hemodynamically stable patient with penetrating abdominal trauma and no evidence of peritonitis or free air on plain radiographs.

A thorough peripheral vascular exam should be conducted during the secondary survey, and carotid, radial, femoral, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses should be documented. Absent, asymmetric, or diminished pulses in the ipsilateral lower extremity, especially with associated abdominal ecchymosis, should prompt suspicion of an arterial vascular injury and requires documentation of ankle brachial indices (ABI). Patients who are hemodynamically stable with an unexplained ABI <0.9 require evaluation either operatively or with angiography for presence of arterial vascular injury.

For patients with known abdominal vascular injuries or penetrating trauma to the abdomen who are definitely headed to the operating room for abdominal exploration, a one-shot intravenous pyelogram (IVP) performed in the emergency department, or in the operating room, can be extremely helpful later, should it become necessary to entertain the option of performing a nephrectomy. This study involves administration of 2mL/kg of intravenous contrast material with the initial fluid resuscitation, a wait time of 5 to 10 minutes, followed by abdominal flat plate radiograph. A one-shot IVP study can identify absence of a functional kidney and provides the surgeon with critical information on bilateral kidney function during laparotomy.

Indications and Contraindications

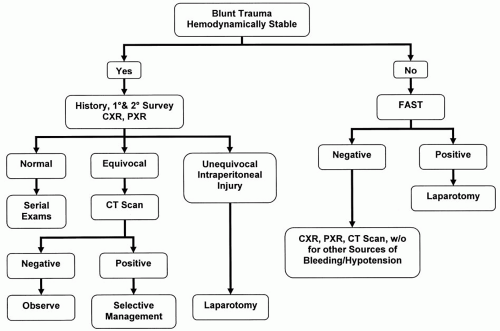

Patients with penetrating injury to the abdominal region who are hemodynamically unstable should be taken directly to the operating room for exploration (Fig. 80-1). Those patients who have peritonitis on physical examination or free air on x-ray should also be operatively explored. In the hemodynamically stable patient, a directed workup is performed and operative management elected if positive findings are elicited. Blunt trauma patients with a positive FAST exam and hemodynamic instability are candidates for immediate operative intervention (Fig. 80-2). If the patient is hemodynamically unstable and the FAST exam is negative, other sources of hemorrhage or hypotension must be elucidated (e.g., pericardial tamponade, hemothorax, pelvic fracture, neurogenic shock, long bone fracture). A patient with a positive angiographic finding of abdominal arterial injury is usually operatively explored unless the injury can be managed nonoperatively (small intimal tears); or in some cases endovascular approaches, such as embolization or stent grafting, have been successful.

Figure 80-1. Algorithm for management of penetrating abdominal trauma. DPL, diagnostic peritoneal lavage; CT, computed tomography. |

Anatomic Considerations

The abdominal cavity and retroperitoneum are divided into distinct zones based on vascular anatomy (Fig. 80-3). Zone 1 covers the entire central region of the retroperitoneum and can be further subdivided into a supramesocolic and inframesocolic domain when assessing a hematoma present in the midline. Within zone 1 is the aorta, inferior vena cava (IVC), celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), and proximal renal arteries. Organs close to the vascular structures in the supramesocolic region of zone 1 that may also be injured include the pancreas and duodenum.

Zone 2 comprises the left and right lateral portions of the retroperitoneum. The left and right kidneys, ureters, and retroperitoneal portions of the right and left colon all reside here. The primary blood vessels are the lateral segments of each renal artery and vein. Zone 3 encompasses the pelvic portion of the vascular system and is home to the common iliac, external iliac, internal iliac, and common femoral blood vessels. Blunt injury to the pelvis with associated pelvic fracture can result in significant injury to the arterial and venous blood vessels of the posterior pelvis. Additional zones of potential abdominal vasculature injury include the porta hepatis and retrohepatic area.

The operative decision as to whether to explore a retroperitoneal or abdominal hematoma is based on the mechanism of injury, anatomic zone, and condition of the patient. An algorithm outlining this decision process is illustrated in Table 80-1. Exploration of the retroperitoneum should be conducted with a sense toward identifying occult injuries to the pancreas, duodenum, posterior colon, kidneys, and bladder that may be associated with vascular structures. The basic principle of proximal and distal control of the vasculature arcade of interest must be followed whenever possible in the trauma patient.

Operative Technique

Operative intervention in the trauma patient ought to be carried out in an appropriate dedicated operating suite specifically outfitted for general, thoracic, and vascular surgery. Prior to beginning the operation, a Foley catheter and nasogastric tube should be in place. The patient should also be positioned

on the operating room table and skin preparation/draping performed in such a way that all potential operative sites can be reached with appropriate incisions. This is usually the supine position with the arms extended to 90°. The patient should be sterilely prepped from the chin to at least one knee for access to the chest, abdomen, and lower-extremity for potential vein graft harvest. All intravenous fluids must be warmed, a cell saver employed if available, and the room temperature adjusted to avoid patient hypothermia. Suitable quantities of potentially needed blood products must be ordered and expeditiously transferred to the operating room.

on the operating room table and skin preparation/draping performed in such a way that all potential operative sites can be reached with appropriate incisions. This is usually the supine position with the arms extended to 90°. The patient should be sterilely prepped from the chin to at least one knee for access to the chest, abdomen, and lower-extremity for potential vein graft harvest. All intravenous fluids must be warmed, a cell saver employed if available, and the room temperature adjusted to avoid patient hypothermia. Suitable quantities of potentially needed blood products must be ordered and expeditiously transferred to the operating room.

Figure 80-3. Anatomical zones of the retroperitoneum: zone 1 (central), zone 2 (flank), and zone 3 (pelvic). |

A midline incision from the xiphoid to symphysis pubis is the standard approach to opening the abdomen in trauma patients. This incision can be extended as a median sternotomy or left/right thoracotomy if necessary. Use of a strong self-retaining retractor that can lift the costal margins up and outward, such as the Rochard or Thompson, can aid in the exposure of bilateral upper quadrants through this incision. A Chevron or transverse incision may be appropriate alternative approaches for a patient with a previous midline incision. The disadvantages of these incisions are that they are potentially time consuming because of the need to divide the rectus muscles and that they provide restricted exposure of the lower abdomen. In general, a large midline incision is preferred, and alternative incisions are rarely helpful in the trauma setting.

Following entry into the abdominal cavity, surgical exploration should proceed in an orderly fashion to minimize hemorrhage and contamination, facilitate the identification of injuries, and minimize operative time. The abdominal organs are initially eviscerated and gross blood and clot evacuated from the abdomen. Large quantities of laparotomy pads should then be used to pack off all four quadrants of the abdomen. Once control of hemorrhage is achieved the anesthesiologist must be allowed to catch up with fluid resuscitation before additional operative exploration is undertaken. Unless there is a discrete site of bleeding, the laparotomy pads should be removed sequentially, working backwards from the site of least hemorrhage or injury to that of most probable bleeding. In situations where a stable hematoma is encountered, associated injuries such as intestinal perforation should be addressed first. However, the presence of an expanding hematoma or free bleeding requires early attention to control and repair vascular injury.

Enteric viscera are inspected starting at the gastroesophageal junction and working distally toward the colon at the peritoneal reflection. The gastrocolic omentum is divided and the lesser space explored, if injury to the stomach is suspected. A Kocher maneuver will facilitate inspection of the duodenum and head of the pancreas. Mesenteric vascular injury can be manifested as a mesenteric hematoma, and expanding hematomas of the mesentery need to be carefully explored. Injuries, lacerations, or missile tracts close to the right and left colon require mobilization of the lateral attachment of the colon to the white line of Toldt so that the posterior retroperitoneal portion of the bowel can be inspected. The final inspection should be to the solid organs, and laparotomy pads packed around the spleen and liver should be carefully removed.

After completion of the peritoneal survey, the retroperitoneum must be evaluated for injury. This involves identification of bleeding or hematomas and their presence in one or more zones of the retroperitoneum. Not all retroperitoneal hematomas require exploration, and the decision as to whether or not to explore one is based on its anatomic location, mechanism of injury, and if it is expanding. The two major approaches to the retroperitoneal vasculature are the right and left medial visceral rotation (Figs. 80-4 and 80-5). The ipsilateral kidney may be included in the dissection, or it may be left posteriorly as the other organs are rotated toward the midline,

depending on what injuries are present and the operative exposure needed.

depending on what injuries are present and the operative exposure needed.

Table 80-1 Management of Intra-Abdominal Hematoma Found at Operation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||