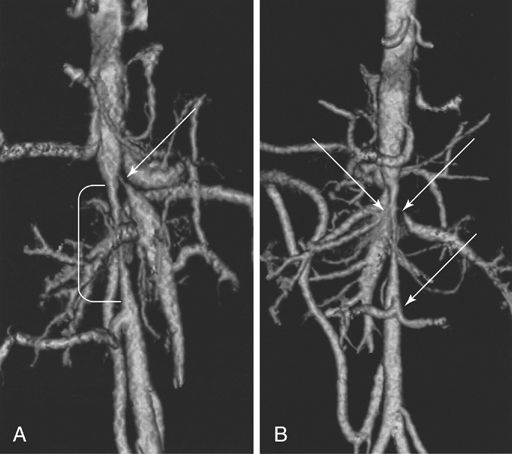

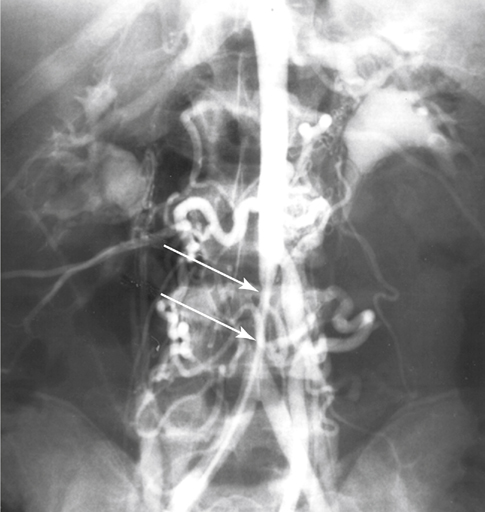

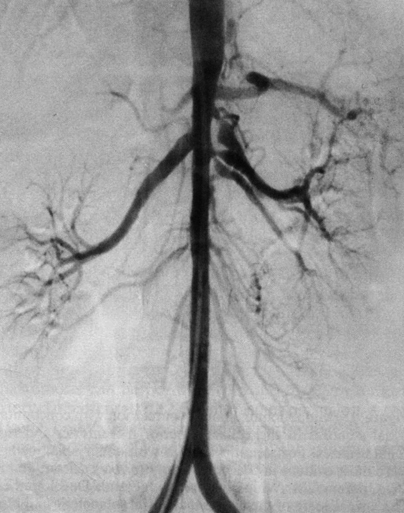

Focal developmental narrowings of the distal thoracic and abdominal aorta are rare anomalies accounting for less than 2% of all aortic coarctations. Most physicians have limited experience with the management of these unusual lesions. Abdominal aortic coarctations are categorized by the most superior extent of the aortic narrowing. Among these aortic coarctations, 69% are suprarenal (Figure 1). Narrowings originating in the intrarenal aorta occur in 23% of patients (Figure 2) and in the infrarenal aorta in 8% of patients (Figure 3). Diffuse involvement of the entire abdominal aorta is usually classified in the suprarenal category (Figure 4). During normal development in most embryos, fusion of the paired dorsal aortas occurs simultaneously with regression of all but one dominant metanephric vessel to each kidney around day 25 of embryonic life. It is speculated that development of a single renal artery to each kidney occurs because of its obligate hemodynamic advantage over adjacent metanephric vessels. By creating local blood flow disturbances with an aortic fusion abnormality, this obligate hemodynamic advantage is lost and additional metanephric channels persist. Support for an overfusion of the two aortas comes from the finding of a single bifurcating distal lumbar artery in up to 55% of patients with abdominal aortic coarctations and aortoiliac hypoplasia (see Figure 1), compared to less than 5% in normal persons. Multiple renal arteries are less likely to develop when the aortic coarctation is distant from the central abdominal aorta.

Abdominal Aortic Coarctation and Hypoplasia

Etiology

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree