TRANSSEPTAL CATHETERIZATION

FOR ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY PROCEDURES

IN CHILDREN AND PATIENTS WITH

CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

EDWARD P. WALSH, RICHARD J. CZOSEK,

JOHN K. TRIEDMAN

Transseptal puncture was already a familiar maneuver in pediatric catheterization laboratories long before the launch of interventional electrophysiologic (EP) procedures. The technique had been employed routinely since the 1970s for accessing left heart structures for hemodynamic data and for angiography in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) whenever a retrograde arterial approach was deemed inappropriate for anatomic reasons.1,2 Thus, when radiofrequency (RF) ablation burst upon the scene some 2 decades ago, the transseptal approach was adopted early at many pediatric centers as a very natural and comfortable method to address left-sided arrhythmia targets.3–5 Experience with transseptal EP procedures in children and in patients with CHD accumulated rather rapidly as a consequence. The fact that this entire textbook is now being dedicated to the topic clearly reflects how indispensable the tool has become for invasive electrophysiologists dealing with patients of all ages.

This chapter will review transseptal EP procedures in children with a focus on techniques needed to maximize safety in a small heart. Additionally, we will attempt to address some of the unique challenges encountered in patients with complex CHD where atrial anatomy is grossly distorted and/ or the intraatrial septum has been modified by a surgical patch or occlusion device that can thwart conventional needle puncture. It should be emphasized that the information contained herein reflects our institutional experience and bias, but that many technical alternatives exist that may be equally effective in experienced hands. We offer our approach as a starting point for electrophysi-ologists involved with children and patients with CHD, but recognize that technology is changing constantly and that each operator must build upon their own clinical experience to arrive at a methodology that best suits their patients’ needs.

Anatomic Features in Small Children and Patients with Congenital Heart Defects

The Normal Pediatric Heart

Safe transseptal catheterization in a child obviously demands strict attention to small chamber size and reduced wall thickness that could increase the risk of needle perforation. On a bright note, the atrial septum in children can often be traversed easily without exposure to the risks of needle puncture owing to a relatively high incidence of a patent foramen ovale (PFO) at younger ages. Pathologic studies have documented that fusion of the septal components (septum primum and septum secundum) is a gradual and imperfect postnatal process, such that the foramen will remain patent to a thin metal probe at autopsy in about 90% of infant hearts, 60% of young children, 40% of adolescents, and about 25% of adults.6 This does not necessarily translate to patency for a catheter or sheath in the EP laboratory since the channel may be narrow and torturous. In practice, a deflectable EP catheter can only be coaxed unaided through the foramen in under half this number of cases, but it’s a sizable percentage nonetheless, and nothing is ever lost by trying. We therefore insist on a routine check for foramen patency with a mapping catheter in all young patients before reaching for a Brockenbrough needle.

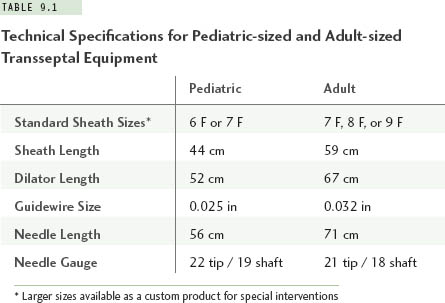

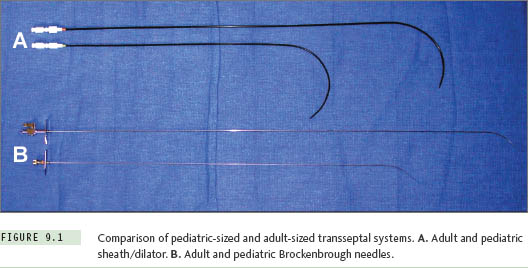

Small atrial chamber size will influence the equipment chosen for transseptal catheterization. For patients with a body weight less than about 30 kg (roughly, age <10 years), the radius of curvature and shaft length on standard adult-sized sheaths and transseptal needles are excessive. It is recommended that special pediatric-sized sheaths and needles be selected for this purpose. Such equipment is available commercially in sizes 6 F and 7 F, with lengths and curve designs that better conform to the geometry of a small heart (Table 9.1, Figure 9.1). At body weights from about 30 kg to 40 kg, the operator can choose either a pediatric-sized or adult-sized apparatus depending upon the individual patient’s body habitus. Selecting the pediatric-sized device in a thin but tall child could result in the 44-cm sheath being too short to reach into the left atrium. If uncertainty ever exists about this choice, one can simply position a pediatric sheath over the surface of the patient’s body between the femoral puncture site and the mid-chest area while looking briefly with fluoroscopy to be assured the sheath tip extends well over the silhouette of the LA. Patients with body weights of more than 40 kg can usually accept standard adult transseptal equipment without difficulty.

A fundamental caveat regarding pediatric catheterization is that subtle hand motions by the operator can result in surprisingly dramatic catheter (or needle) motions relative to the small cardiac chambers of young children. Clinical experience and a rather “gentle touch” are mandatory to perform transseptal EP procedures safely in this population.

Special Atrial Features in Patients with Congenital Heart Disease

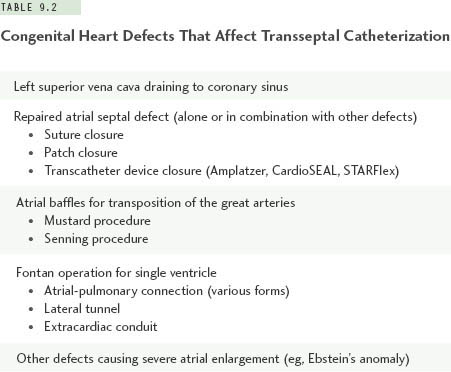

In both children and adults with CHD, transseptal EP procedures demand that the operator have clear understanding of the underlying anatomic defect as well as details of all surgical interventions. Those CHD lesions that impact most significantly on gross atrial anatomy and status of the intraatrial septum are listed in Table 9.2.

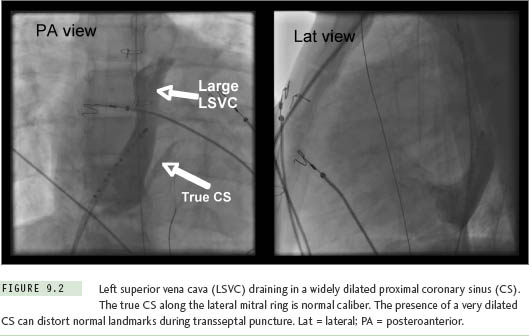

On the simple end of this spectrum is the phenomenon of a left superior vena cava (LSVC) draining into the coronary sinus (CS). This normal variant can seriously distort landmark recognition during transseptal puncture in patients of all ages. The diagnosis might be overlooked on a preablation transthoracic echocardiogram in patients with poor acoustic windows, but should be nearly impossible to miss as soon as an EP catheter is advanced toward the CS at the beginning of a study (Figure 9.2). The CS (including its orifice) will be enlarged to many times normal diameter, and catheters will enter and advance very easily along its length, with unexpected deviation toward the left neck rather than following the lateral mitral ring.7 Failure to recognize an LSVC-to-CS can complicate transseptal puncture since the true septum is foreshortened and the needle falls easily into the CS orifice where advancement can be hazardous. Accurate orientation for septal puncture in these cases can be obtained with the aid of angiography, intracardiac echocardiography (ICE), or transesophageal echocardiography.

Transseptal catheterization in patients with repaired atrial septal defects (ASD) can range from straightforward to very demanding depending on size of the original defect and the method of closure. Patients who had a small ASD repaired surgically with primary suture closure can be regarded as having nearly normal anatomy. Their septum may be slightly thicker than usual and more resistant to needle advancement, but it is unnecessary to modify technique to any significant degree. A larger ASD closed with a surgical patch is another matter. Various materials are used for this purpose, including glutaraldehyde-fixed pericardium, GORE-TEX, and on rare occasion, Dacron. All three materials become covered with endothelial tissue of unpredictable thickness after implant, and with time will become stiff or even calcified. More recently, a growing number of patients with a small- to moderate-sized ASD are being treated with transcatheter devices, including the Amplatzer wire mesh design (AGA Medical Corporation, Plymouth, MN) and the STARFlex or CardioSEAL double-umbrella designs (NMT Medical, Inc, Boston, MA).8,9 As will be discussed in detail later in this chapter, atrial patches and occlusion devices do not preclude transseptal catheterization, although some modification in technique is usually required.

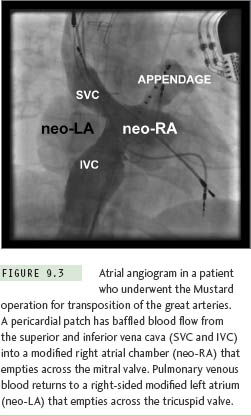

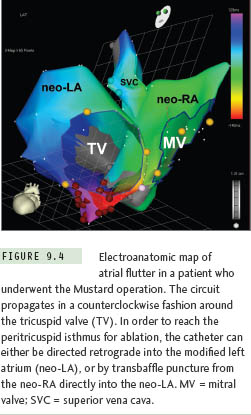

Gross distortion of atrial anatomy and septal configuration can occur after CHD operations that involve large intraatrial baffles to redirect systemic and pulmonary venous return. The Mustard and Senning procedures for transposition of the great arteries are illustrative examples of this challenge, and because these repairs result in a very high incidence of postoperative atrial tachyarrhythmias, transseptal ablation procedures are required commonly.10 As part of both operations, blood return from the superior vena cava (SVC) and inferior vena cava (IVC) is channeled to the mitral valve, leaving the pulmonary veins and tricuspid valve on the left side of the circulation (Figure 9.3). Importantly, the cavotricuspid isthmus (the most common target for atrial flutter ablation in these cases) is longitudinally transected by the baffle suture line; as a result, complete isthmus interruption will typically require ablation within the left heart (Figure 9.4). The tricuspid valve isthmus region can sometimes be reached with a retrograde arterial approach,11–13 but baffle puncture14 has recently become the preferred option in our institution.

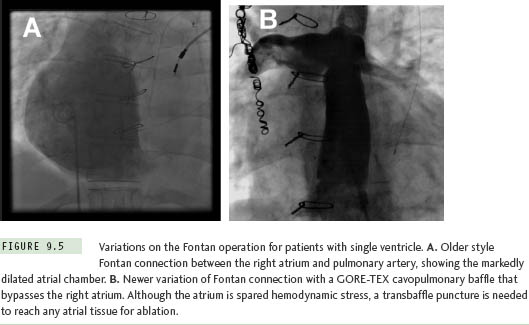

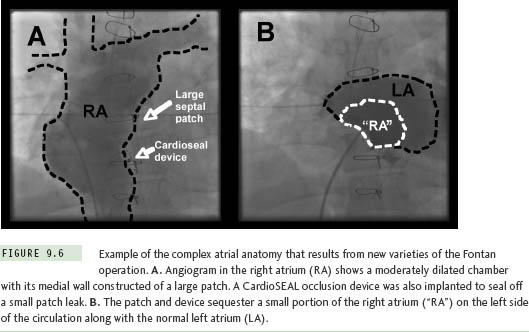

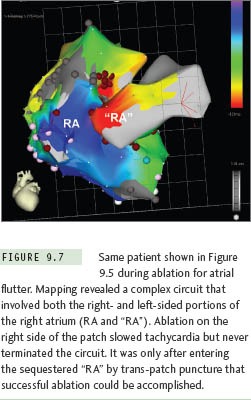

The Fontan operation for CHD patients with single ventricle is another situation where extensive atrial baffling is performed, in this case to redirect SVC and IVC return into the pulmonary arteries. Similar to the Mustard and Senning populations, a high postoperative atrial tachycardia burden results in the frequent need for ablation therapy in these patients.15 There have been several variations on the Fontan procedure over the years (Figure 9.5). Older surgical techniques retained the RA chamber in its entirety on the right side of the circulation, and although this resulted in a massively thickened and dilated RA,7 most arrhythmias could be mapped and ablated within this chamber without resorting to transseptal access. However, in efforts to reduce hemodynamic stress on RA tissue, surgery has now evolved toward a system of baffles or tubes that channel SVC and IVC flow more directly to the lungs, and, in so doing, sequesters large portions of the RA on the left side of the circulation (Figure 9.6). These newer surgical designs have significantly reduced arrhythmia incidence in Fontan patients,16 but have not eliminated the problem entirely. Thus, on those occasions when ablation does become necessary, a transseptal approach is almost invariably required. These are without a doubt the most difficult transseptal procedures in the CHD population. Even when the baffle or tube is crossed successfully, the atrial architecture on the left side involves a complex maze of RA and LA tissue, along with remnants of the atrial septum, all of which can seriously confound catheter movement and mapping (Figure 9.7). In its most extreme form, the Fontan operation can bypass the RA completely using an extracardiac conduit running from the IVC to SVC that is then attached into the pulmonary arteries. This conduit may be sufficiently close and adherent to the lateral wall of the RA to permit a cautious attempt at needle puncture between the tube and the atrial wall, and some centers have even gone so far as to recommend needle puncture through the anterior chest wall directly into the LA when the caval return is connected in this fashion,17 but experience with these rather daunting techniques remains extremely limited.

Basic Techniques for Transseptal Access in Pediatric Patients

This section will describe in detail the methodology currently in use at Children’s Hospital Boston18 for transseptal access during EP procedures. These recommendations stem from an institutional experience with more than 1000 transseptal ablation procedures involving children and CHD patients since 1990.

Most procedures in our laboratory are performed under general anesthesia, which may improve safety in anxious youngsters by eliminating unpredictable body motion at times when a transseptal needle is extended out of the sheath.19 However, we do not hesitate to perform transseptal punctures in children under carefully titrated conscious sedation should the need arise.3,20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree