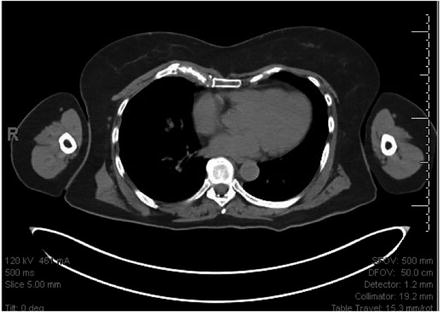

Fig. 8.1

Chest radiograph of large left chest wall tumor found to be poorly differentiated carcinoma with extensive necrosis

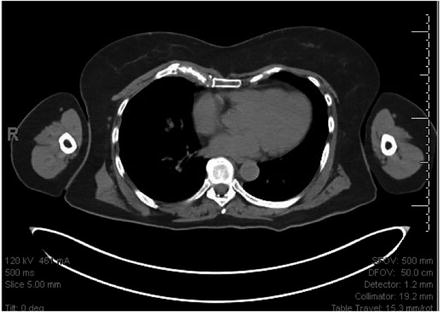

Computed Tomography (CT) : If contrast is used, CT scan can provide information about the vascularity of a tumor, location, and composition of a chest wall mass, as well as appraisal of the extent of tumor invasion and involved structures. It is also better at predicting cortical bone involvement. Cartilaginous matrix calcifications are better defined with CT than with MRI which is very useful for preoperative planning [6]. It can also be useful in confirming histologic diagnosis by obtaining a CT-guided biopsy of a lesion. The approach for biopsy should be chosen together with the surgeon, with consideration given for preoperative planning (Fig. 8.2).

Fig. 8.2

Axial CT scan of chest wall sarcoma demonstrating osseous destruction of right anterior third rib

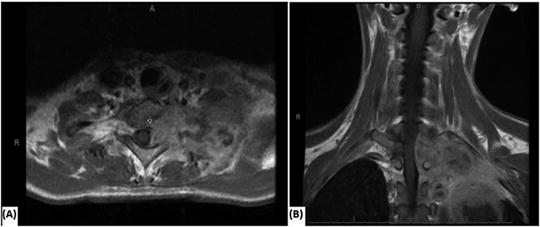

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) : Accurate tissue characterization can be obtained with MRI due to its superior tissue-resolving features and multiplanar image acquisition, which makes it an important assessment tool [5, 7]..It is the most accurate study for spinal involvement, characterizing soft tissue involvement, and further delineating between vascular, soft tissue, and nerve involvement [3, 6, 8] (Fig. 8.3).

Fig. 8.3

MRI scan of left chest tumor in a patient with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma invading the thoracic spine causing cord displacement and rib destruction (a) axial view and (b) coronal view

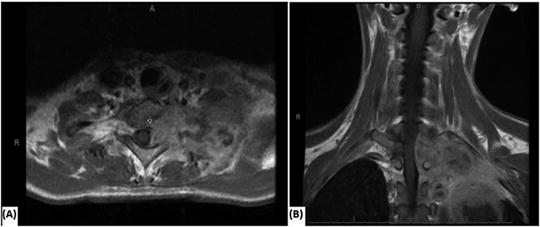

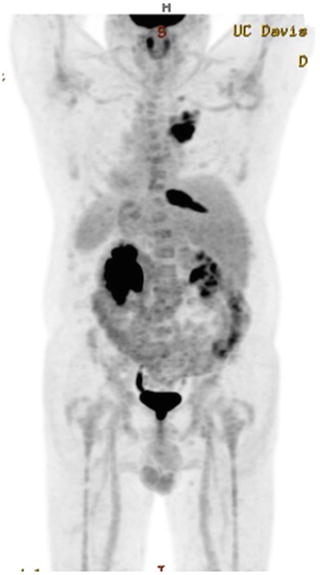

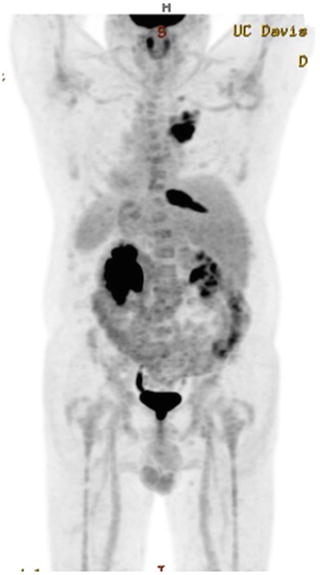

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) : The clinical significance of standard uptake value (SUV) may be useful but has not been formally established as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of chest wall lesions [9, 10]. There is some data suggesting that PET may be more accurate for determining the extent of large tumors, especially those >5.5 cm [10, 11]. Though, it is not routinely discussed as a common imaging modality in the evaluation of chest wall tumors, there seems to be increasing frequency of its mention in the literature. In a small recent study by Petermann et al., PET imaging was found to be superior to CT for defining the extent of chest wall tumors, giving hope that it will be found to be of significant diagnostic value in larger prospective studies, which have yet to be conducted [11]. In the case of malignant disease, it may be useful for defining patients with limited disease versus disseminated disease (Fig. 8.4).

Fig. 8.4

Maximum Intensity Projection image from PET/CT demonstrating isolated metastasis to the right tenth rib from NSCLC

Ultrasound (US) : There has recently been documented use of ultrasound for more clearly defining tumor margins [6, 10, 12]. Ultrasound may accurately predict the degree of tumor invasion or extension, which could help with preoperative planning to ensure negative surgical margins [10]. Caroli et al. describe the absence of lung sliding on ultrasound as being accurately predictive for lung invasion from a chest wall tumor in 8/8 patients where other imaging modalities were inconclusive [12].

Biopsy

In the majority of cases, radiographic features alone are insufficient to make a complete diagnosis; therefore, histologic evaluation is required. Suitable modalities to obtain tissue diagnosis include fine-needle aspiration, incisional biopsy, or excisional biopsy [9]. The approach to obtaining a biopsy is guided by the size and location of the lesion, extent of resection, complexity of any associated need for reconstruction, and if there are any associated comorbidities. Typically, lesions less than 2–5 cm undergo excisional biopsy depending on the suspected pathology and the surgical center [2, 3, 10]. An absolute diagnosis prior to resection is usually of value for lesions greater than 5 cm, given the increased likelihood of extensive dissection and complex reconstruction. Therefore, lesions greater than 2–5 cm may undergo needle aspiration or incisional biopsy for confirmation of diagnosis, allowing for better operative planning [2, 3, 10]. Core needle biopsy may determine if it is a benign or malignant process but may not obtain sufficient sampling for further histologic analysis or genetic testing.

It is essential that the entire treatment plan be considered before any biopsy to ensure correct placement of the biopsy location. The lesion is often approached directly in order to avoid contamination of surrounding structures. If a malignant diagnosis is obtained, definitive excision is required, which necessitates total excision of the biopsy tract. It is preferable, for the earlier reasons , that the biopsy be performed at the treating/surgical center rather than at the referring center, or in coordination with the operating surgeon.

Preoperative Evaluation

Once the diagnosis has been made, and the primary excision is determined, it is important to complete a thorough history and physical with careful consideration of any past surgical history or treatment which may affect approaches for resection or reconstruction. Immunosuppression, history of radiation or planned radiation, and previous chest procedures should all be considered. Additionally, full medical assessment should be obtained, including a cardiac and pulmonary function evaluation in cases where there is concern for simultaneous pulmonary resection. As mentioned earlier, complete radiographic analysis is essential to operative planning and may delineate the need for preoperative consultation with neurosurgical or reconstructive specialists. Patients with extensive or complicated lesions are best served with a multidisciplinary approach, which may include cardiothoracic surgery, spine surgery, plastic surgery, radiation oncology, and/or medical oncology [10, 13].

Pathology

Benign

Benign chest wall tumors are less common than malignant lesions and arise from nerve, blood vessel, osseous, cartilaginous, or fatty tissue [5]. It is crucial that malignant diagnoses are definitively ruled out with radiographic and histologic analysis for any of these lesions.

Skeletal Lesions

Benign chest wall tumors of bony origin are less common than malignant bony lesions. However, one should always assume a malignant condition until proven otherwise.

Osteochondroma

Osteocondroma is the most common type of benign bone tumor and is typically found in the femur, humerus, and tibia [14]. In the chest, osteochondromas are most common in the rib or scapula, where they are commonly found at the costochondral junction, and they develop from abnormal growth of normal tissue [5, 10]. Osteochondromas make up 50 % of benign rib tumors [2]. These masses frequently cause pain as they progress with growth of bony exostoses [14]. Peak incidence is in the second decade of life [15]. It is one of the few chest wall tumors where a definitive diagnosis can be made on CT or MRI based on the appearance of the cortex and medullary space blending into the underlying bone [5], and punctate or flocculent calcifications with mineralized hyaline cartilage cap [3]. Surgical treatment is resection and provides complete pathologic evaluation, symptomatic relief, and minimizes the risk of malignant transformation [16]. Cartilage caps greater than 2 cm in adults and greater than 3 cm in children are suspicious for malignant degeneration [3, 10].

Chondromas (Enchondromas)

Chondromas are also typically found at the sternocostal junction arising from cartilaginous tissue [2, 10]. They are relatively common, making up 15–20 % of benign chest wall lesions. Chondromas are usually painless, slow growing, osteolytic lesions, and present between 20 and 30 years of age. The distinction between chondroma and low-grade chondrosarcoma is difficult. Therefore, all chondromas are treated as malignant lesions, and wide excision is recommended [4]. Appropriate wide excision for a malignant lesion is commonly accepted as full thickness resection with 4-cm margins and en bloc removal of one rib above and below the lesion as well as intercostal muscles, pleura, and wide clear margin of adjacent tissue [17, 18].

Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia typically appears in the lateral or posterior tract of the ribs and is the third most frequent benign chest wall lesion [2]. Normal bone is replaced with fibrous tissue forming a slow-growing mass, which can cause pathologic fractures and result in pain; otherwise, presentation may be as an asymptomatic mass in the posterior aspect of a rib. Fibrous dysplasia appears as a lytic lesion on chest radiograph with a soap bubble or ground-glass appearance that is diagnostic. Only one bone is involved in 70–80 % of the cases [5], most commonly the second rib [10]. In 25 % of cases it affects more than one bone [15]. When this occurs, it may also be associated with cafe-au-lait spots and endocrine abnormalities with the constellation of abnormalities known as McCune–Albright syndrome [3, 15]. It typically occurs in the second and third decade of life with no disparity in gender ratio [3]. Treatment is wide local excision for relief of symptoms and confirmation of diagnosis [4]. Conversely, some sources believe that excision is not necessary if the lesion remains asymptomatic, as imaging is often diagnostic [10].

Eosinophilic Granuloma /Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Eosinophilic granuloma, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis , is a less common tumor that can arise in the anterior chest wall [4]. This results from idiopathic proliferation of histiocytes, considered to be of bone marrow origin. These masses tend to present with chest pain, fevers, and an isolated tender mass that has a typical lytic appearance on radiograph and chest CT [19]. Eosinophilic granuloma is a diffuse infiltrative inflammatory process that can affect many organs and can also manifest with an associated leukocytosis. In the chest wall, it can cause destruction of bone cortex and new subperiosteal bone formation that can mimic osteomyelitis or malignancy [4]. Treatment in the literature varies ranging from nonsurgical approaches such as steroids, chemotherapy, and low dose radiotherapy without surgical excision [3] to wide local excision performed both for diagnosis and symptomatic relief [19, 20]. Most forms are treated nonsurgically, but if the lesion is isolated, then resection and curettage are reported to have good results [10]. This lesion requires a histologic diagnosis, with identification of birbeck granules on electron microscopy [3]. If a procedure is necessary for diagnostic purposes, then it often makes sense to pursue excisional biopsy at the time.

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

Aneurysmal bone cysts are a rare, benign, locally aggressive entity consisting of an expanding osteolytic lesion with blood-filled cystic spaces. Their etiology is not clear, as they are often associated with abnormal bone or are found in the setting of another underlying bone tumor [10]. They are usually found on the posterior chest wall and 75 % present before the age of 20 [3]. If there is soft tissue extension, then it may be difficult to differentiate from sarcomas. Complete excision is recommended, with cure rates of 70–90 % [10]. Radiation is sometimes used for local control in the setting of aggressive or recurrent tumors [10]. These lesions are not known to metastasize.

Osteoid Osteomas

Osteoid Osteomas are small, tumors of osteoblastic origin that rarely occur as primary chest wall tumors [15]. They often present in the first and second decades with nocturnal pain, which is improved by NSAIDs [3, 10]. The most common location for presentation is the posterior spine and ribs and can also be associated with scoliosis. Radiographically, they have a small radiolucent lesion with thick sclerotic margin of reactive bone and surrounding soft tissue edema. Their characteristic appearance on bone scan is known as the double density sign [15]. Treatment generally involves radiofrequency ablation.

Osteoblastoma

Osteoblastoma is a rare osteoblastic tumor thought to be on the continuum of osteoid osteomas [3, 10]. These tumors also primarily affect the posterior ribs. On radiologic evaluation they appear as well-defined expanding osteolytic lesion, but with a sharp sclerotic rim and lack of a central nidus. They can be locally aggressive with potential for recurrence, and thus wide local excision is the preferred treatment [15].

Giant Cell Tumor

Giant cell tumors are more common and occur most frequently between the second and fourth decades [10], with men having a higher occurrence than women [3]. They are considered locally aggressive with 30–50 % recurrence rates and rare reports of metastasis [3]. Secondary to their locally aggressive nature, wide local excision is recommended [10]. They are osteolytic lesions with cortical thinning and often are associated with a soft tissue mass (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1

Benign bony lesions

Tumor | Origin | Presentation | Imaging characteristics | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Osteochondroma | Cartilage | Rib, scapula, 50 % of benign rib tumors. Peak incidence in second decade | Cortex and medullary space blends w/ underlying bone, punctate or flocculent calcifications w/ mineralized hyaline cap (>2 cm cap in adults or >3 cm in children = ↑ risk of malignant transformation) | Resection |

Chondroma (enchondromas) | Cartilage | Usually painless lesion at 20–30 year of age, most commonly found in anterior ribs | Osteolytic, lobulated appearance with distinct boarders | Wide local excision—distinction from low-grade malignant chondrosarcoma is difficult |

Fibrous dysplasia | Fibrous tissue | Lateral or posterior rib. Slow growing. Often w/pathologic fracture @ 20–30 yo | Lytic lesion. Soap bubble or ground glass appearance = diagnostic | Wide local excision for symptoms and definitive diagnosis vs. no intervention if diagnosis confirmed and remains asymptomatic |

Eosinophilic granuloma (langerhans histiocytosis) | Bone marrow | Anterior chest wall, ribs, sternum. Rare. | Focal lytic radiolucent lesions with biopsy necessary for diagnosis (birbeck granules on histology) | Most forms treated nonsurgically. If the lesion is isolated, then resection and curettage are reported to have good results |

May have pain, fever, leukocytosis | ||||

Giant cell tumor | Osteoclast | 20–40 yo with ♂ > ♀ | Osteolytic lesions with cortical thinning, often with soft tissue mass | Wide local excision recommended secondary to locally aggressive nature and rare ability to metastasize |

30–50 % risk of recurrence | Vascular sinuses w/giant cells and spindle cells | |||

Aneurysmal bone cyst | Unclear | Posterior chest wall, <20 yo, rare, locally aggressive. can coexist with other lesions | Cystic, expanding osteolytic lesions. Free fluid w/ multiseptated hemorrhagic cysts which are not pathognomonic | With complete excision, cure rates 70–90 %. Radiation may be used for aggressive disease or recurrent tumors |

Osteoid osteoma | Osteoblast | Nocturnal rib pain that responds to NSAIDs and Tylenol, first–second decade of life. Often posterior, may be associated with scoliosis | Small radiolucent lesion with thick sclerotic margin of reactive bone with soft tissue edema. Characteristic appearance on bone scan = double density sign | Radiofrequency ablation? |

Osteoblastoma | Osteoblast | Posterior/ posterio-lateral rib mass or pain | Well-defined osteolytic lesion with sharp sclerotic rim and lack of a central nidus | Can be locally aggressive and recurs, wide local excision is recommended |

Soft Tissue Tumors

Soft tissue tumors that affect the chest wall have a similar variability in pathology of that of the bone-based lesions. Cutaneous nevi, lipomas, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, and neurogenic tumors are some of the benign lesions that can be found in the soft tissue of the chest wall. They are treated with wide local excision to negative margins to avoid local tissue recurrence. Soft tissue tumors have some additional challenges to preoperative diagnosis. Intercostal hernias have been reported to be confused with benign soft tissue lesions, mandating appropriate radiographic confirmation of clinical suspicion based on history and physical exam [21]. Radiographic evaluation may not always definitively address malignancy but will assist in operative planning.

Lipomas

Lipomas usually present as well-circumscribed adipose masses but are often deeper and larger on the chest than on other sites of the body [3]. They are more prevalent in the obese and older patients, with incidence highest at approximately ages 50–70 [3]. As with many chest wall tumor presentations, they can sometimes be challenging to evaluate with radiographic modalities, and are often difficult to differentiate from low-grade liposarcomas [3]. There have been case reports of soft tissue lesions with preoperative imaging suggestive of intrathoracic or chest wall invasion, which were subsequently found to be giant benign lipomas on excision [22, 23]. Chest wall lipomas should be excised for symptomatic relief and complete diagnostic evaluation secondary to the risk of malignant transformation.

Lymphangiomas

Lymphangiomas of the chest wall can be cystic or cavernous in nature and are a result of a developmental malformation. They can be located within the mediastinum or the chest wall itself. Preoperative CT imaging is essential to assess the extent of the lesion, as several reports of giant lesions exist in the literature [24, 25]. Complete surgical excision is required for excellent prognosis and avoidance of long-term lymphatic fistula formation. Nonoperative therapy with radiation or sclerosing agents remains controversial for lymphangiomas of the chest wall, with surgery as the standard of care [2].

Hemangiomas

Hemangiomas arise from blood vessels and can be found within the chest wall or protruding through the chest wall from the thoracic cavities or mediastinum and arise from blood vessels. Often seen as heterogeneous soft tissue masses with fatty, fibrous, and vascular elements on CT scan [3]. Ultrasound may be a useful modality to evaluate flow within the lesion [3]. MRI is used to distinguish benign from malignant lesions based on phleboliths, fat component, and high intensity and fat suppression on T2 imaging technique, but surgical biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis [26]. Hemangiomas of the chest wall can be intramuscular, intercostal, or cavernous . They tend to occur in patients less than 30 years of age and present as painful masses. Treatment is complete surgical excision if symptomatic, but local recurrence rates are as high as 20 % [27].

Neurogenic Tumors

Neurogenic tumors of the chest wall include neurofibromas and neurilemomas that arise from peripheral nerve sheaths and are usually associated with neurofibromatosis. Presentation is often between the ages of 20 and 30 and are seen as slow growing homogeneous masses on CT and MRI [3]. These lesions may undergo cystic degeneration creating a target appearance on MRI. As one may expect, biopsy is extremely painful. Surgical excision is usually only recommended for cosmetic reasons for cutaneous lesions, as there is a low likelihood of malignancy. However, plexiform lesions that are increasing in size or becoming symptomatic should be completely excised without preoperative biopsy [28].

Desmoid Tumors

Desmoid tumors arise from musculo-aponeurotic structures and are considered myofibroblastic or fibroblastic in origin. They can develop anywhere in the body, but are most common in the abdomen and extremities, with only 10–28 % arising in the chest wall [1, 10]. The most frequent location in the chest wall being in the shoulder girdle [18]. Their histology is benign, but because of their aggressive growth rates and tendency to grow into nearby structures or cause compressive symptoms, they can be considered malignant. Desmoid tumors are common in females and males, usually younger than 40 years and can be found in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis, where they are related to a mutation in the APC gene. Desmoids can also occur in sites of previous trauma, scar, or radiation. Presentation can consist not only of a palpable chest wall mass/swelling and associated pain, but dyspnea, cough, shortness of breath, and dysphasia have all been reported [18]. The latter symptoms possibly being the result of tumor mass effect. Resection to tumor-free margins is needed for cure, which is difficult to achieve given high incidence of microscopic positive margins [10, 18]. This clearly reinforces the need for wide margins at the time of original resection. Again, appropriate wide excision for a malignant lesion is commonly accepted as full thickness resection with 4-cm margins and en bloc removal of one rib above and below the lesion as well as intercostal muscles, pleura, and wide clear margin of adjacent tissue [17, 18]. When negative margins are not possible, radiation should be considered, though the effectiveness of radiation treatment for nonresectable disease, recurrence, or to treat positive margins, remains with uncertain efficacy [10, 29]. Recurrence rates for desmoid tumor are high. Abbas et al. report 5-year probability of developing a local recurrence as 37 %, with an 89 % rate in patients who had positive margins at the time of resection [17].

Elastofibromas

Elastofibromas classically occur in the subscapular region, with peak incidence between 40 and 70 years of age. This lesion has a female predominance and a characteristic layered appearance with mild enhancement on CT scan performed with IV contrast [10]. Recommended treatment is complete excision, with intention of cure (Table 8.2).

Table 8.2

Benign soft tissue lesions

Tumor | Origin | Presentation | Imaging characteristics

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|