Women and Heart Disease

EPIDEMIOLOGY/SCOPE OF PROBLEM

Cardiovascular disease (hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and coronary artery disease [CAD]) is the leading cause of death for women in the United States, killing approximately 500,000 women annually. CAD is responsible for half of those deaths. This may in part be due to the lack of awareness among women: although ultimately 1 in 2.4 women will die from cardiovascular disease, compared to 1 in 30 women from breast cancer, many women consider breast cancer to be their greatest potential health problem. These attitudes are beginning to change as the National Health Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in 2001 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 have undertaken national education campaigns to educate women and their physicians regarding women’s risk for cardiovascular disease.

One reason that heart disease has usually been thought of as a disease that primarily affects men is that clinical manifestations typically occur in women 10 years later than in men. As a consequence, historically there has been a tendency for women to be underrepresented in national trials studying risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment for CAD, heart failure, and arrhythmias. Despite this neglect, “optimal care” for treating women with these problems has been extrapolated from predominantly male patient data. More recent studies have attempted to improve the recruitment of female patients as well as to conduct separate analyses on the specific treatment effects on women, in order to identify possible differences in outcomes based on gender.

RISK FACTORS FOR CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

The standard risk factors for CAD include diabetes, elevated cholesterol, hypertension, smoking, and a positive family history of the disease. Although risk factors for CAD are similar in men and women, the effects of the individual risk factors as well as interventions can differ dramatically based on gender. Thus, in order to appropriately diagnose and treat CAD in women, we need to understand the pertinent risk factors and determine the effects of modifying these factors on disease progression. Although these risk factors are common in women of all racial and ethnic groups in the United States, they are more prevalent among socioeconomically and educationally disadvantaged women. Data from 2008 for women ≥18 years old in the United States showed that more than a third had hypertension, more than a third had low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL, approximately a fifth were cigarette smokers, more than 60% were either overweight or obese, and more than two-thirds led a sedentary lifestyle.

Diabetes

Diabetes is the most powerful risk factor for CAD in women. Not only does diabetes increase the risk of CAD fivefold, the risk of myocardial infarction (MI) twofold as well as the risk for developing congestive heart failure or dying post-MI, but it also eliminates the 10-year gender gap in risk for CAD.

Hyperglycemia decreases estradiol-mediated nitric oxide production, thus causing endothelial dysfunction and platelet aggregation. Diabetes is also associated with abnormalities of platelet function and coagulation factors. Diabetics have elevated levels of fibrinogen, factor VII, and fibrinopeptide A, all markers of a hypercoagulable state. Also, women have increased platelet response and reactivity compared to men, which compounds the effects of hyperglycemia.

Elevated Cholesterol

While there is a strong association between total cholesterol and LDLs and CAD in men, there is only a very weak association in women and none at all in women ≥65 years of age. In older women, low HDL and elevated triglycerides are strong risk factors for CAD. Total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) ratio (which should be ≤4) is a more accurate predictor of CAD risk in women of all ages. The average HDL-C level in adult premenopausal women is 20% higher than in age-matched men. Although HDL-C declines following menopause, it still remains higher than in men.

Several secondary prevention studies have assessed the effect of treatment of lipid abnormalities in women. The CARE (Cholesterol and Recurrent Events) trial, which studied pravastatin as treatment in patients with average cholesterol levels and prior MI, found a 46% reduction in death or recurrent MI in treated patients (as compared with a 26% reduction in men). The 4S trial (Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study) investigated the use of simvastatin in patients with known CAD. The outcome was a 35% reduction in relative risk for coronary events in women (compared with a 34% reduction in men). The LIPID (Long Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischemic Disease) trial studied patients with prior MI or unstable angina who were treated with pravastatin and found a 24% decrease in CAD events.

Primary prevention studies include the AFCAPS/Tex-CAPS (Air-Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study). Patients were men and postmenopausal women with average total cholesterol and LDL-C levels but belowaverage HDL. Long-term lipid-lowering treatment decreased the incidence of a first major acute CAD event by 46% in women and by 37% in men. There are no data to support aggressive lipid lowering in premenopausal women without CAD or family history or multiple risk factors.

Hypertension

More than 50 million people in the United States have been diagnosed with hypertension, and >60% of these individuals are women. However, there is a lower prevalence of hyper tension in women until the sixth decade at which point the prevalence in women begins to exceed that in men. Hypertension is more likely to cause a cardiovascular event in women and is a risk factor for congestive heart failure in women. Nonetheless, women are more likely than men to be aware of their diagnosis, to receive treatment, and to reach target blood pressure.

Etiology

The origin of hypertension is predominantly essential. Etiologies that are seen exclusively or disproportionately in women include hypertension associated with pregnancy or use of oral contraceptives (especially older agents with higher doses of estrogens and progestins) and renovascular hypertension, which has a female:male ratio of 8:1.

Treatment

Antihypertensive treatment recommendations are generally similar for women as compared to men except in certain situations.

Pregnancy: Methyldopa is generally preferred and ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are contraindicated.

Pregnancy: Methyldopa is generally preferred and ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are contraindicated.

Elderly: Thiazide diuretics may be helpful as they have been shown to reduce hip fracture.

Elderly: Thiazide diuretics may be helpful as they have been shown to reduce hip fracture.

The following side effects have been demonstrated to be more frequent in women:

Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia

Hypokalemia

Hypokalemia

ACE-inhibitor induced cough

ACE-inhibitor induced cough

Peripheral edema from calcium channel blockers

Peripheral edema from calcium channel blockers

Hirsutism from minoxidil

Hirsutism from minoxidil

Smoking

Cigarette smoking is the leading preventable cause of death in men and women in the United States. Women who are heavy smokers (>20 cigarettes a day) have two- to fourfold increased risk of coronary disease compared with nonsmokers. Even light smokers (1 to 4 cigarettes a day) have a two- to three-fold risk of fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) or nonfatal MI. Second-hand smoke may increase risk of CAD by 20%.

The prevalence of smoking has declined in the United States since 1965, but more men have been successful at quitting than women. There are multiple factors in women’s failure to quit, including fear of weight gain and lack of confidence.

Mechanisms by Which Smoking May Increase Risk of CAD

Chronic smokers are insulin resistant, hyperinsulinemic, and dyslipidemic compared to nonsmokers. (There is a dose–response relationship between number of cigarettes smoked and plasma cholesterol, possibly due to increased lipolysis.)

Second-hand smoke may cause intimal wall damage and accelerate atherosclerotic plaque formation. In young women, the combination of smoking and use of oral contraceptives promotes thrombogenesis.

Smoking Cessation Decreases Risk

The Nurses’ Health Study showed a 30% decrease in risk for CAD in 2 years following cessation of smoking. There is continued decline in risk over next 10 to 15 years, and then the risk is at the same level as that of a nonsmoker.

Most studies show a 30% to 50% decrease in risk for CAD in the first 2 years following cessation.

Obesity and Sedentary Lifestyle

Obesity is an independent risk factor for CAD in women. In the Framingham Heart Study, relative weight in women was positively and independently associated with the development of CAD as well as mortality from CAD and cardiovascular disease. In the Nurses’ Health Study, women with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29, had an age-adjusted relative risk for CAD of 1.8, whereas those with BMI ≥ 29 had a relative risk of 3.3, compared with women of ideal BMI.

Truncal obesity correlates with increased LDL-C and decreased HDL-C and also is associated with hyperinsulinemia and hypertension. Although obesity is associated with diabetes (insulin resistance), hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia, the waist/hip ratio still correlates positively with CAD after controlling for smoking, hypertension, glucose intolerance, lipids, and BMI.

AHA 2011 GUIDELINES FOR HEART DISEASE PREVENTION IN WOMEN

The 2011 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) guidelines for heart disease prevention in women are evidence based and provide individual recommendations for women (see Tables 56.1 and 56.2). In general, the recommendations differ very little from those for men.

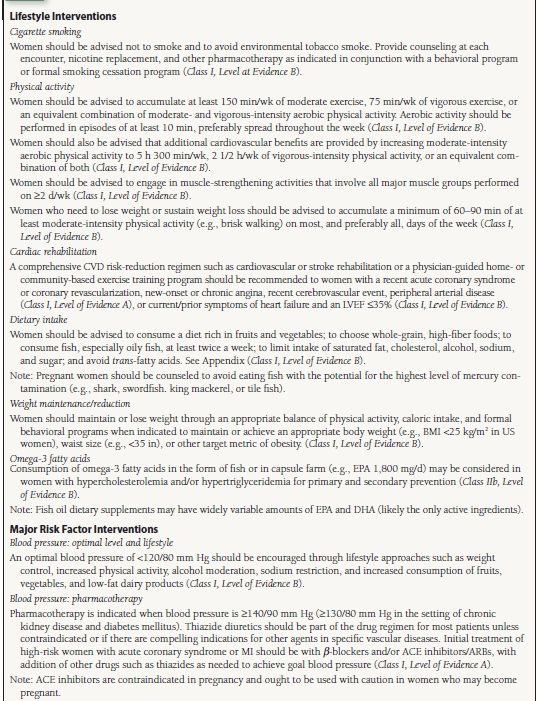

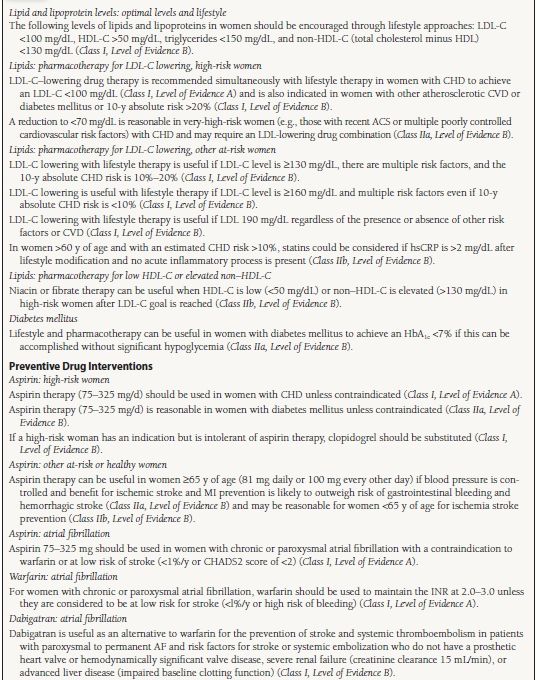

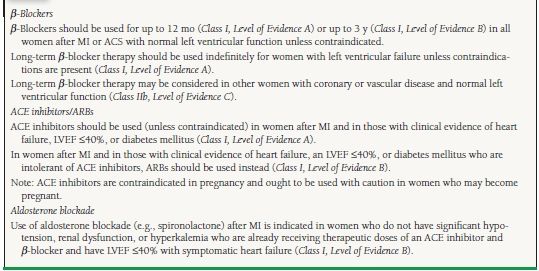

TABLE

56.1 Guidelines for Prevention of CAD in Women: Clinical Recommendations

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BMI, body mass index; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1C; MI, myocardial infarction; CHADS2, Congestive Heart Failure, Hypertension, Age, Diabetes, Prior Stroke; and INR, international normalized ratio. Reprinted from 2011 Writing Group Members, Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (Updating the 2007 Guideline): A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123:2022–2060, with permission.

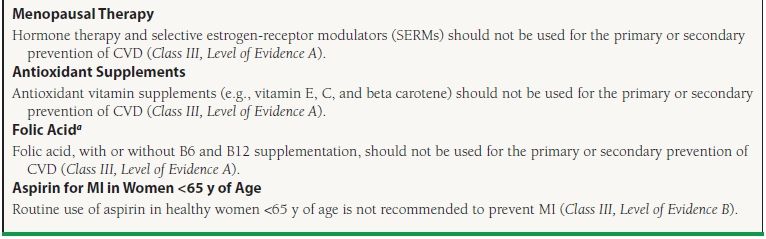

TABLE

56.2 Class III Interventions (Not Useful/Effective and May Be Harmful) for CAD or MI Prevention in Women

CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

aFolic acid supplementation should be used in the childbearing years to prevent neural tube defects.

Reprinted from 2011 Writing Group Members, Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (Updating the 2007 Guideline): A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123:2022–2060, with permission.

Women are grouped into high-risk (includes risk for CHD event of ≥10% over the next 10 years, women with CHD, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral arterial disease, chronic kidney disease, or abdominal aortic aneurysm), at-risk (includes women with systemic autoimmune collagen-vascular disease, history of preeclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, or gestational diabetes along with other traditional risk factors), and ideal cardiovascular health. As compared to the 2007 guidelines, the 2011 guidelines have decreased the threshold at which women are considered to be high-risk (from risk for CHD event over the next 10 years of ≥20% to ≥10%).

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE: ESTROGEN THERAPY FOR PREVENTION OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Physiologic Effects of Estrogen

Benefits

Beneficial effects on lipid profile

Beneficial effects on lipid profile

Antioxidant effects

Antioxidant effects

Reduction of serum fibrinogen

Reduction of serum fibrinogen

Inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia, smooth muscle cells, and collagen biosynthesis

Inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia, smooth muscle cells, and collagen biosynthesis

Potentiation of endothelium-derived relaxing factor

Potentiation of endothelium-derived relaxing factor

Calcium channel blocking effect

Calcium channel blocking effect

Increases prostacyclin biosynthesis

Increases prostacyclin biosynthesis

Decreases insulin resistance

Decreases insulin resistance

May cause favorable distribution of body fat

May cause favorable distribution of body fat

Risks

Breast cancer: relative risk is 1.35 with >10 years of hormone-replacement therapy (HRT).

Breast cancer: relative risk is 1.35 with >10 years of hormone-replacement therapy (HRT).

Endometrial cancer: relative risk is 8.22 with >8 years of HRT.

Endometrial cancer: relative risk is 8.22 with >8 years of HRT.

Risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE) is doubled with HRT.

Risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE) is doubled with HRT.

Risk of gall bladder disease is doubled with HRT.

Risk of gall bladder disease is doubled with HRT.